How Facebook Algorithms Can Fight Over Your Feed

How Facebook Algorithms Can Fight Over Your Feed

(Bloomberg) -- Over the past decade, most of us have gotten used to hearing that “the algorithm” is responsible for this or that on the internet. Sometimes it’s something useful, like movie recommendations. Sometimes it’s not. Facebook is under fire for the way its algorithms shape what nearly 3 billion users see on the world’s largest social media network, including troubling amounts of hate speech and misinformation. But internal company documents provided by a whistle-blower make clear that it’s wrong to think of “the algorithm” as a single bad actor: What users of Facebook and other online platforms see can be the result of a tangle of conflicting algorithms, reflecting their creators’ sometimes contradictory goals. Legislators determined to rein them in are just beginning to grapple with the legal and technical challenges.

1. What is an algorithm?

A set of instructions for making a decision or performing a task. Arranging names in alphabetical order is a kind of algorithm; so is a recipe for making chocolate chip cookies. But those simple formulas bear only a distant relationship to the computerized code that companies that Facebook parent company Meta Platforms Inc., Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Twitter Inc. spend billions of dollars on each year.

2. What are those like?

Typically, algorithms are written to instruct a computer on how to perform a discrete task. But many algorithms can work in concert to produce enormously complex systems. At Facebook and Google, the algorithms powering the platforms are constantly updated to learn from new data. While they can appear to operate independently, the decisions about what signals to train the software on and what outcomes to aim for are entirely human and reflect their builders’ goals. As one internal memo recently revealed by whistle-blower Frances Haugen, a former Facebook product manager, put it, “The mechanics of our platform are not neutral.”

3. How does Facebook use algorithms?

Facebook’s business model is centered on selling ads to be viewed by users. It had $86 billion in revenue in 2020, a reflection of its huge reach and success at keeping users clicking. One of Facebook’s most important algorithms is the one that produces the news feed on a user’s page. Before 2009, the algorithm reflected the chronological order in which items were posted. But starting that year, the feed began to be ordered in a more complex way by an algorithm designed to show people what it judges they would find most interesting or engaging, not just most recent. Facebook also uses algorithms to target ads and recommend friends or groups to follow.

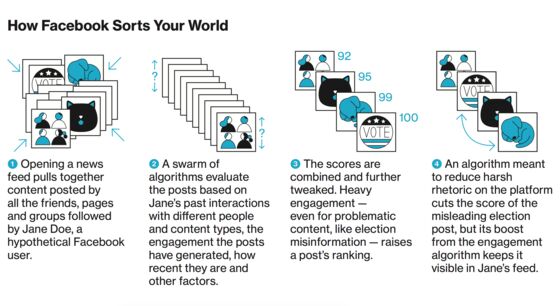

4. How do its algorithms work?

The billions of pieces of content posted on Facebook are all ranked in terms of an individual user’s likely reaction. That is, the algorithms make predictions based on each user’s characteristics and past behavior, as well as the nature of the content and how such posts have previously been received. Like many companies, Facebook uses algorithms powered by artificial intelligence that are designed to improve with use. Feeding and improving such algorithms is a big reason why social media companies collect, store and curate vast amounts of data about users.

5. How can algorithms clash?

Facebook says it also designs its system to reduce content that might be offensive or distasteful. Facebook changes the settings of a variety of algorithmic elements from time to time. But the internal documents provided by Haugen, show that the complexity created by multiple algorithms working together meant that tweaking it is not a simple matter. For instance, a 2018 shift to focus on “meaningful social interactions” in the news feed ended up increasing polarization on the platform. Algorithms that boosted content that garnered strong user engagement sometimes wiped out attempts to automatically “demote” harmful content. Haugen said Facebook executives chose to shelve proposals that might have reduced the problem but decreased profits.

6. What else did the documents show about algorithms?

A common complaint from Facebook employees was that there was no centralized vision for what kind of experience a user should have, as directed by the platform’s algorithms. A member of the Integrity team who was leaving the company wrote in a parting note that “harms fester in unwatched interactions” between different parts of the platform. What Haugen called the company’s “flat” corporate structure made it hard to implement proposed interventions to address harmful content. For example, one internal study found that demoting “deep reshares” from people who weren’t a friend or a follower of the original poster could cut the number of times so-called civic misinformation was viewed by 25% and civic photo misinformation views by 50%. Haugen said this intervention was discussed with senior management but never implemented, in part because Facebook didn’t want to lose the reader engagement driven by deep reshares. Joe Osborne, a Facebook spokesperson, said the company sometimes reduces deep reshares, but only rarely, because it is a blunt instrument that affects benign speech along with misinformation.

7. What else does Facebook say?

That it’s been trying to give people more control over the content in their news feed. The platform now has an easier way for users to say they want more recent posts, rather than machine-ranked content, and people can mark some friends or sources of information as favorites. Facebook also suggests that users hide posts they don’t like, an action that would signal to the algorithm to show fewer posts like those.

8. Do other social media companies have similar issues?

Facebook is definitely not alone. Other social media platforms including Twitter, YouTube, TikTok, LinkedIn and Pinterest all use algorithms to show users content relevant to their demographics and past interests. They also use algorithms as the first filter to identify low-quality or harmful information, with varying degrees of success. YouTube in particular has drawn ire for algorithmically produced recommendations that have been shown to lead viewers toward divisive or inflammatory content or misinformation.

9. What’s being done about it?

- In the U.S., proposals before Congress include measures that would require companies to spell out how they use algorithms; create a government task force to establish safety standards for algorithms and investigate charges of discrimination; and mandate an option to choose chronological ranking of content. Another proposal would strip the liability protection known as Section 230 from any online platform that uses an algorithm that “materially contributed to a physical or severe emotional injury.”

- The U.K. and the European Union are both working on bills that don’t focus on algorithms but would threaten platforms that fail to limit illegal and harmful content, such as disinformation. They could face massive fines, up to 6% of global revenue in the EU version and 10% in the U.K.’s.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg News articles on Facebook’s role in the Jan. 6 insurrection, and how it promoted fake news and incendiary images in India.

- A report from Facebook’s Oversight Board faulted the company for a lack of transparency on how it handled high profile users.

- Bloomberg QuickTakes on Facebook’s conflicts with former President Donald Trump, its role in the debate over children and screen time.

- A Bloomberg QuickTake on the rising calls for antitrust action against technology giants like Facebook and Google.

- A Bloomberg QuickTake on algorithmic bias.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.