How Deutsche Bank Drifted Into Its Whirlpool of Woes

How Deutsche Bank Drifted Into Its Whirlpool of Woes

(Bloomberg) -- At this point, Deutsche Bank AG’s biggest problem may be how many problems it has, how long they’ve gone on and how they’ve fueled one another. Years of low profits at Germany’s biggest bank have spawned a long series of failed turnaround plans and a steady departure of senior executives. Chief Executive Officer Christian Sewing has unveiled a last-ditch effort to salvage what’s left by racing to dramatically shrink and reshape its operations around the globe.

1. What’s gone wrong?

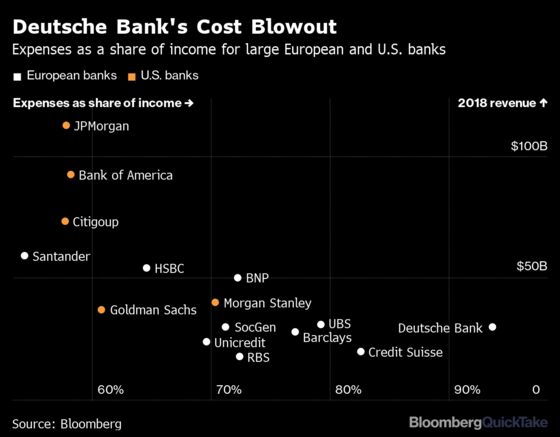

The bank has long been caught in a downward spiral of declining revenue, sticky expenses, lowered credit ratings and rising funding costs. It’s repeatedly tried to reverse the slide, without success. Problems include outdated technology, a talent drain and heavy fines -- $18 billion in the decade since the financial crisis -- for misconduct. Adverse market conditions including negative interest rates have compounded the homemade difficulties. The bank’s shares lost more than half their value in 2018, and in 2019 they remained down about 90% from their 2007 peak.

2. Why hasn’t it been able to turn itself around?

It’s been cutting costs to pare down to a more profitable size, but it’s been losing business even more quickly. The investment banking division, once responsible for more than half of revenue, has lost market share to rivals that were quicker to fix balance-sheet and governance weaknesses after the 2008 financial crisis. The issues facing Deutsche Bank are also affecting many other European banks. The European Central Bank is expected to hold interest rates below zero for years to come, meaning revenue at bank retail units is likely to stay depressed. For Deutsche Bank, the situation is made worse by the low share it commands in its fragmented home market, where numerous smaller banks keep margins razor-thin.

3. What’s the turnaround strategy?

Sewing has been accelerating cost cuts and scaling back global ambitions. In his latest revamp, unveiled in July 2019, the bank is pulling out of equities trading and seeking to cut the workforce by a fifth. Deutsche Bank had just under 90,000 employees at the end of the third quarter, down from just over 97,000 when Sewing took over in April 2018. While the restructuring means the bank will continue to shrink for some time, the CEO seeks to grow the core businesses by shifting away from the lender’s focus on institutional clients toward meeting the trade finance and cash management needs of large companies.

4. How would that restore the bank’s health?

The idea is simple: Stop spending money on businesses that haven’t turned a profit in years and free up funds for profitable units that Sewing hopes to grow. Exiting equities trading and reducing fixed-income trading has left Deutsche Bank with 360 billions euros ($396 billion) worth of assets -- a quarter of its total balance sheet -- that it no longer wants and has moved into a wind-down unit. That solution is sometimes referred to as a “bad bank.” Capital currently allocated to those assets will be released as they melt off the balance sheet and will then be shifted to higher-earning areas.

5. Why are the cuts so deep?

The bank was running out of options after a long series of more piecemeal turnaround plans stretching over almost a decade -- including Sewing’s first effort in 2018 -- all fell short of restoring an acceptable level of profitability. Official merger talks with domestic rival Commerzbank AG and unofficial ones with UBS Group AG went nowhere either, leaving few alternatives. The turnaround plan was put in place once regulators made clear they wouldn’t oppose drawing down the bank’s capital buffers as a way to cover the restructuring costs. Any move to raise fresh money would have met with strong opposition from existing shareholders.

6. How did it come to this?

Deutsche Bank, which will mark 150 years in business in March 2020, is reversing its aggressive growth of the 1990s and 2000s, when the bank expanded rapidly overseas and took greater risks, at one point becoming the world’s largest lender and a top trading firm. Years of expansion and takeovers left the bank with multiple fiefdoms and competing centers of power. Then in the wake of the 2008 crisis, both its business model and its reputation came under attack.

7. Can the new plan succeed?

Sewing has the backing of key investors, regulators and even the government, giving him a degree of control over the bank that proved elusive to his predecessors. He’s already chalked up a few successes, most notably transferring the business of servicing hedge funds to BNP Paribas and selling various portfolios of other unwanted assets. But he faces an uphill battle as negative interest rates persist and Europe faces an economic slowdown. Just a few months into the plan, he’s already had to put a question mark over the bank’s revenue target and some of his leadership decisions have raised eyebrows among regulators. Crucially, the bank will need to stay above the minimum amount of capital he’s set as dipping below could force him to ask shareholders for fresh money.

8. How will we know if it’s working?

Deutsche Bank needs to show it can cut costs without causing its core business to shrink. Sewing has said a few quarters of delivering on that promise would instill confidence among investors and lift the lender’s share price. A higher market capitalization could also open the door to renewed efforts to merge with another European bank. Should the turnaround fail, it’s hard to see how the lender can avoid anything short of a break-up, an end to its global investment bank or a similarly radical scenario. Given its crucial role in keeping Germany’s export economy humming, it could even face the prospect of being nationalized.

The Reference Shelf

- A story listing the key elements of Deutsche Bank’s latest plan

- An inside account of how the plan came about

- QuickTakes on Europe’s rickety lenders and a “bad bank.”

- An interactive chart on Deutsche Bank’s long tab of legal probes

- Deutsche Bank third-quarter results cast doubt on Sewing’s plan.

- Columnist Elisa Martinuzzi warns of ‘misplaced optimism’ about the plan

- Regulators are skeptical of Sewing’s board nominee

--With assistance from Yalman Onaran and Nicholas Comfort.

To contact the reporter on this story: Steven Arons in Frankfurt at sarons@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Sree Vidya Bhaktavatsalam at sbhaktavatsa@bloomberg.net, ;Dale Crofts at dcrofts@bloomberg.net, Leah Harrison Singer, Ross Larsen

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.