Cybersovereignty

Cybersovereignty

(Bloomberg) -- Early on, the narrative around the internet was that it would be unfettered and borderless, a global commons. That didn’t last long. Chinese President Xi Jinping has led the way in asserting what’s become known as cybersovereignty. That means government control over how the internet is run and used, as well as what happens with the troves of user data generated – an immensely valuable resource in the digital economy. Other authoritarian regimes have followed suit. The U.S. and other democracies also have taken steps to secure control over local data, including going after Chinese-owned apps such as TikTok, even as they defend an open internet as promoting free speech and innovation. Perhaps a divide was inevitable as it became clear the internet isn’t just a pipeline for exchanging information but also a powerful tool for economic and political purposes.

The Situation

The model embraced in China combines strict data controls with sweeping content curbs. Services from Facebook Inc., Twitter Inc. and other U.S. companies are kept out (which also cleared the way for pliant, domestic tech giants such as Weibo, Baidu and WeChat to emerge). A 2017 law requires that personal data generated in-country be stored in-country — and be accessible on demand to state officials. U.S. officials justified their attack on TikTok by saying the data it collected on American users could end up in the hands of the Chinese government, making it a national security threat. Meanwhile, the CLOUD Act empowers U.S. authorities to order American technology companies to hand over data stored anywhere in the world. Such moves have countries in Europe and elsewhere worried about threats to their sovereignty and their ability to protect sensitive or commercially valuable information. (More than 100 countries have some sort of data sovereignty laws in place, according to David Gilmore, chief executive officer of DataFleets Ltd., an enterprise software firm.) Russia’s “sovereign internet” law allows authorities to track and selectively block information flows nationwide, and even disconnect from the outside world in a crisis. Cybersovereignty has also been portrayed as a form of techno-nationalism, with India, for example, banning dozens of Chinese-made apps in June as border tensions flared between the two neighbors.

The Background

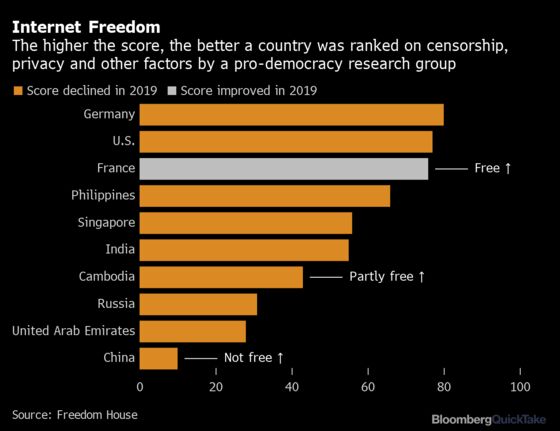

Cybersovereignty enables both cybersecurity, the protection of things such as transportation networks, electrical grids and election systems, and censorship, the suppression of information for political or other purposes. It has implications as well for all the information that’s shared in today’s digital world, the so-called big data that can be parsed, analyzed and then exploited. Companies use it to target advertising, hone their products or develop “deep learning” algorithms and other cutting-edge technologies. Much of that data migrates to the so-called cloud — online computing and storage — where it can be vulnerable to tampering or theft.

The Argument

Chinese officials say their approach is necessary to preserve the stability of a vast country undergoing rapid economic and social changes. Xi, who chairs China’s top policy-setting body for cyberspace, also has repeatedly underscored the importance of building an independent cyberspace that foreigners can’t disrupt. Russian President Vladimir Putin has called his country’s 2019 law a response to the threat of surveillance by the U.S. The national security argument carries over into infrastructure and equipment. Trump cited fears about potential spyware and hidden back doors when he moved to effectively bar Huawei Technologies Co., China’s largest tech company, from the U.S. market — and has been pressing U.S. allies to do the same. Ex-Google Chief Executive Officer Eric Schmidt predicted in 2018 that within a decade, the internet will split in two, with one led by the U.S. and the other by China. Tech companies worry that a profusion of regulatory regimes would hinder innovation and raise costs. The Asia Internet Coalition, which counts Google, Amazon, Apple, Line, Grab and Rakuten among its members, warned Vietnam that the requirement in its new law to store data locally would have “serious consequences for economic growth, investor confidence and opportunities for local businesses.” More governments, though, are viewing data as a resource to be protected not only for privacy but to help in developing technologies such as artificial intelligence. European companies and the French and German governments have created a cloud computing initiative, known as Gaia-X, that aims to provide a homegrown alternative by 2021 to U.S. technology giants. A draft of India’s nascent e-commerce law stated: “Indian citizens and companies should get the economic benefits from the monetization of data.”

The Reference Shelf

- More QuickTakes on China’s Great Firewall, on VPNs and more U.S.-China flashpoints.

- Bloomberg’s look at why Putin wants his own internet, too.

- The late John Perry Barlow reassessed the independence of the internet in 2006.

- The Guardian on how countries are asserting their cybersovereignty.

- Freedom House’s 2019 report on internet freedom.

- A deep dive on how France is ditching Google to reclaim its online independence.

- Politico explains Germany’s plan to control its own data.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.