How Booming Population Is Challenging Africa

How Booming Population Is Challenging Africa

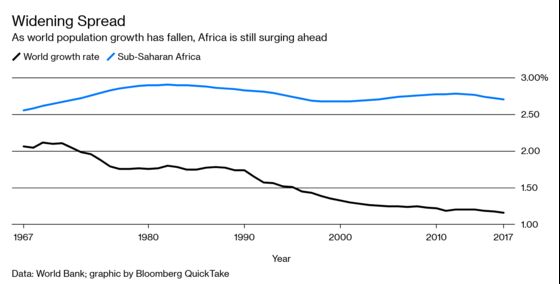

(Bloomberg) -- The world’s developed economies are facing a decline in fertility so pronounced that some will see their populations -- and economies -- shrink in years ahead. Sub-Saharan Africa faces the opposite situation: Its population has more than doubled in the past three decades and is expected to triple again by the end of this century. While the growing number of young, working-age people creates economic opportunities, it’s not clear how governments will manage the boom and whether the path to prosperity followed by other developing regions -- shifting into manufacturing -- is still available. Will the benefits of a more crowded Africa outweigh the drawbacks, or are its problems too dire and its governance too weak?

1. Why the surge?

Population growth in sub-Saharan Africa owes primarily to better medical care, which has slashed infant and child mortality and raised average life expectancy from 50 to 61 since 2000. The population has soared to about 1.1 billion and it could hit 4 billion by 2100, says the United Nations. Nigeria alone is predicted to double to 400 million people by the middle of the century, making it the world’s third-most populous country after China and India. Sub-Saharan Africa’s per-capita gross domestic product has climbed 40% since the start of the century to $1,652, compared with $1,987 in India. However, oil and mineral riches mean a handful of nations are 10 or more times wealthier than a score of others that remain desperately poor.

2. How could Africa benefit?

Almost 60% of sub-Saharan Africans are younger than 25, compared with one-third in the U.S. This “youth bulge” could translate into an ample and energetic workforce. But the benefits accrue only when greater prosperity reduces fertility rates. If the next generation has fewer babies than their parents, the proportion of working age people would rise relative to the number of their dependents -- mainly children and the elderly -- creating a so-called “demographic dividend.” Smaller families allow more women to secure paid work, and parents and governments are able to invest greater resources in each child. That’s what happened as Asia and Latin America developed, but Africa’s fertility drop-off is forecast to take much longer due to deep-seated cultural attitudes and pervasive poverty.

3. What’s the biggest challenge?

Jobs. The African Development Bank estimates that more than 10 million new jobs must be created each year just to absorb the number of young people entering the workforce. Increased automation in manufacturing might squeeze off a traditional source of employment growth, so some countries are pinning their hopes instead on services. Call centers and other kinds of outsourcing operations have opened in South Africa and cities such as Lagos, Nigeria and Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Tourism has overtaken coffee and tea exports as the top foreign currency earner in Rwanda.

4. What needs to change?

Education. Almost a third of children in sub-Saharan Africa don’t attend school, and on average just 4% of the population completes university. The region also struggles to feed its population, with one in four classified by the UN as malnourished. To move beyond subsistence agriculture, politicians must invest billions in public services and infrastructure such as water and electricity to serve a rapidly urbanizing citizenry. Mali and Uganda have improved roads and transport links to boost exports of mangoes and fish, while Ethiopia is building Africa’s largest hydroelectric plant, on the Blue Nile, to control flooding and generate power. Governments also must tackle environmental degradation, including worsening pollution and deforestation.

5. Can Africa’s population growth be slowed?

Yes, though progress has been slow compared with other regions. Women have 4.8 live births on average, down from 6.8 in the late 1970s but still nearly three times the number in Europe and North America. Rwanda encouraged family planning and made contraceptives available at clinics, driving its fertility rate down by more than half, to 3.8 over the past 20 years. But many other countries still fall short: on average, sub-Saharan African women have two more children than they want to, and in 14 countries, they average five or more children.

6. What if Africa can’t absorb all those people?

Overcrowded countries such as the Philippines, India, Bangladesh and Indonesia have seen waves of workers move abroad to fill jobs in more developed places and send earnings back home. While Africans are starting to follow suit, the outflows come as doors that were open for others may already be closing. In Italy, populist leaders are responding to rising anti-immigration sentiment by turning away the boatloads of Africans trying to reach Europe illegally across the Mediterranean.

The Reference Shelf

- A report from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation that assesses progress in the fight against poverty in Africa.

- Bloomberg Economics analysis on the need for Africa to boost its productivity.

- A Financial Times article cautioning that Africa can’t count on a demographic dividend.

- The UN Population Division’s data portal.

--With assistance from Mark Bohlund (Economist).

To contact the reporters on this story: Mike Cohen in Cape Town at mcohen21@bloomberg.net;Leanne de Bassompierre in Abidjan at ldebassompie@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Karl Maier at kmaier2@bloomberg.net, Andy Reinhardt, Antony Sguazzin

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.