How a Deluge of Downgrades Could Sink the CLO Market

How a Deluge of Downgrades Could Sink the CLO Market

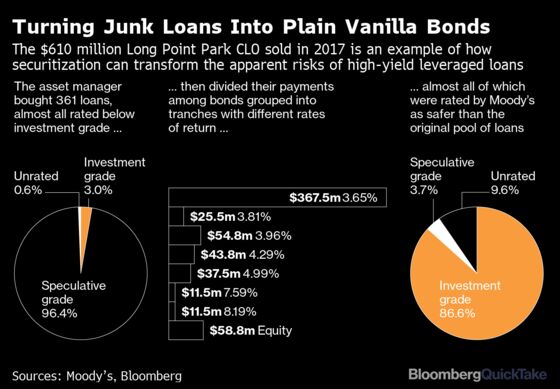

(Bloomberg) -- It takes a large dose of Wall Street alchemy to create the structured finance products known as CLOs, which fund much of corporate America. So collateralized loan obligations naturally came under particular scrutiny as the scale of the coronavirus pandemic became clear in March. Since then, many pockets of the financial markets have rebounded feverishly. But CLO investors are still bracing for the worst: Many expect a cascade of downgrades that will ripple through these complex securities, testing the internal mechanisms designed to protect them.

1. How bad is it?

As CLO managers make their required disclosures over the next several months, the scale of the problem is expected to unfold. By mid April, some analysts were expecting as many as 1-in-3 CLOs may have to limit payouts to holders of the riskiest and highest-returning parts of their structures. Others say the pain could quickly spread to less risky tranches, too. There were warning signs: Key parts of CLOs were conspicuously absent from the rally that lifted U.S. stocks in April. Lower-rated bonds in the almost $700 billion market remained deeply depressed, typically fetching less than 70 cents on the dollar.

2. What makes CLOs such a worry?

CLOs fared well in the 2008 crisis, with none of the highest-rated tranches defaulting. But they’re a perpetual worry because they’re forged from the debt of companies with less-than-stellar credit scores. These are companies with a lot of debt relative to income and cash flow, and are thus among the most vulnerable to the economy’s collapse. A CLO is a package of some 150 to 300 so-called leveraged loans, so an individual downgrade likely wouldn’t damage a CLO’s ability to pay investors. But a deluge of them around the same time -- as is happening now -- certainly could, especially when loans are slashed to the lowest rating tier of CCC or Caa.

3. How does that work?

Most CLO structures limit the worst-rated loans to a maximum of 7.5% of the portfolio, the so-called CCC bucket. The limit is designed to protect investors from managers who may otherwise be tempted to take outsized bets to juice returns by loading the portfolio with higher-yielding, lower-rated loans. Any CCC loans over the limit will be suddenly subject to mark-to-market rules, which means they’ll be counted at the current trading value rather than at par, reducing the value of the entire portfolio. That puts the CLO at risk of failing a critical test that measures asset-coverage, also known as the over-collateralization, or OC test. Failing that test cuts off cash-flow streams to certain investors -- a mechanism designed to protect those who purchase less-risky segments of the CLO bonds.

4. Is this a car crash?

Maybe. Ratings companies were roundly criticized during the last financial crisis in 2008 for acting too slow in sounding the alarm over deteriorating credit. This go-around they are being far more proactive and have embarked on an unprecedented downgrade spree. As the pandemic throttled the global economy, S&P Global Ratings and Moody’s Investors Service have cut ratings on some 20% of the loans that are housed in CLOs. The loan downgrades have come so fast, one after another, that Stephen Ketchum of Sound Point Capital Management likened it to a spill “at the Daytona 500, where the cars are crashing into each other.”

5. How do loan downgrades flow through to CLOs?

The pace of loan downgrades has been so frenetic that it threatens to overwhelm safeguards on CLOs that are put in place to ensure the financial strength of the securities. Already the vast majority of CLOs have blown past the CCC cap, up from a mere 8% that were breaching buckets earlier this year, according to research by Bank of America analysts. In addition, some 20% of CLOs that submitted their monthly reports indicated that they are failing tests and will be turning off some cash flow to equity investors. Things are so bad that a few were even failing tests that measure asset coverage of the highest rated AAA/AA tranches, according to an April 20 report from the bank.

6. Can they stem the rot?

Portfolio managers can be left with two unpleasant options: Dump lower-rated loans at fire-sale prices or cut cash payments to some of their investors. In the first case, selling loans can cause a CLO to crystallize losses -- a likely event because lower-rated loan prices are lagging. The other path of turning the cash spigot off and shifting to payment-in-kind, or PIK, where interest is paid with more debt, can ravage equity returns, depress lower-rated CLO bonds and cut off a substantial portion of the CLO manager’s fees.

7. Who are the losers?

The barrage of loan downgrades will prompt ratings companies to also downgrade the securities sold by the CLOs themselves, which are separate from the ratings on the underlying loans. On April 17, Moody’s surprised the market by putting $22 billion of U.S. CLO bonds -- nearly a fifth of all such bonds it grades -- on a watchlist for a downgrade, saying that the expected losses on CLOs have increased materially. Some 40% of those securities had investment-grade ratings. Among the buyers of CLOs are so-called rating- constrained investors, such as banks and insurance companies. If CLO bonds are downgraded -- particularly if they go from investment-grade to a junk tier -- investors may be forced to sell them or risk higher capital charges.

8. Who are the winners?

The turmoil has so far produced at least one winner. Citigroup Inc. made more than $100 million in April trading a huge swath of the highest-rated CLOs as market turmoil prompted asset managers in need of liquidity to unload securities at steep discounts. Some investors including Napier Park Global Capital and Neuberger Berman are prepping new credit funds specifically designed to take advantage of the dislocation in lower-rated CLO bonds. If history is a prelude to the future, there will be opportunities to buy beaten-up loans and produce equity returns to rival those seen following the financial crisis.

9. Are CLO investors fleeing?

So far, they aren’t fleeing en masse. CLOs lock in capital for years, and aren’t subject to withdrawal pressures. There’s an active secondary market, where investors can swap positions and leave the CLO intact. But the onslaught of downgrades and fears of impending defaults have quashed new deals. Deutsche Bank cut its forecast for new U.S. CLO sales in 2020 by 40% to $55 billion.

10. How bad could it get?

The cascade of downgrades signaled that a wave of defaults is coming. Analysts have hiked their expectations for how many of the underlying loans will sour, and lowered their forecasts for how much might be recovered from each bad loan. U.S. high-yield default rates could run to double-digits, perhaps surpassing heights of about 15% in the last financial crisis. Loan recovery rates could be slashed to 60 cents or less, far lower than past norms. But history provides only a limited guide: The market for leveraged loans has exploded in recent years, with U.S. total issuance ballooning to $1.2 trillion as the market became the go-to place for private equity firms to finance debt-fueled buyouts.

The Reference Shelf

- How trades with extreme leverage are suddenly getting tested by the Covid-19 pandemic.

- A look at Wall Street’s “CLO machine” and the fortunes it made.

- How CLO managers prepared at the start of 2019 for a possible economic downturn.

- A top Federal Reserve official’s 2018 warning that CLO investors may be taking on too much risk.

- Related QuickTakes on the history of leveraged loans and CLOs, plus how they’re different than junk bonds and why they’re loved by Japanese investors.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.