Hong Kong’s Autonomy

Hong Kong’s Autonomy

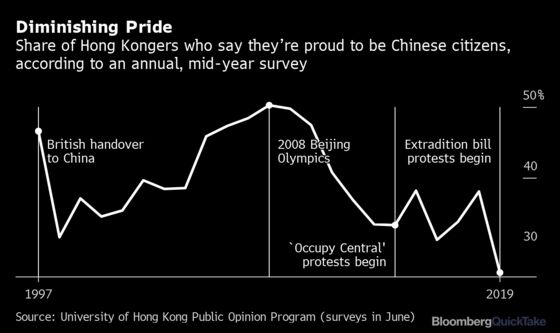

(Bloomberg) -- The British gave Hong Kong back to China more than two decades ago, but the city of 7.5 million people is still very different from the rest of the country. An international financial center, it has a vibrant free press, for example, and an independent judicial system. But its freedoms may prove fleeting. In 2019 a proposal to allow extraditions to the mainland provoked waves of unrest as residents reacted to what they viewed as the latest threat to the city’s semi-autonomous status. The protests echoed those of 2014, which were also about growing Chinese government control. Such strains are ever-present in Hong Kong, while the democracy that protesters demand remains elusive.

The Situation

Peaceful protests that began early in 2019 grew by June into marches of historic proportions, drawing hundreds of thousands of people. They were quickly overshadowed, however, by outbreaks of violence and a broader challenge to Beijing’s tightening grip on Hong Kong. The spark was the extradition bill, which opponents feared would open the door for anyone who runs afoul of the Chinese government to be arrested and sent to the mainland. Hong Kong’s leader, Chief Executive Carrie Lam, eventually withdrew the bill, but protesters expanded their demands to include direct elections for the city’s top job — something Hong Kong has never had. Masked protesters flinging Molotov cocktails clashed repeatedly with riot police firing tear gas, rubber bullets or — at times — real ones. The main legislative building was ransacked along with subway stations, Chinese bank branches and other property. As demonstrators complained of police brutality, the government banned face coverings and some subway stations were sporadically closed in an effort to damp the violence. Speculation grew that China may resort to sending in troops — a notion given extra resonance by the passing of the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, when hundreds, maybe thousands, of demonstrators were slain in Beijing. Against the backdrop of a trade war between China and the U.S., events in Hong Kong stoked a broader culture clash in other arenas; America’s National Basketball Association lost most of its Chinese sponsors after a team manager tweeted support for the protesters, while U.S. lawmakers infuriated Chinese authorities by inviting activists to Washington and taking up legislation backing the pro-democracy movement.

The Background

The 1984 Sino-British power transfer agreement specified that China would give Hong Kong a “high degree of autonomy” for 50 years under a principle the Chinese call “one country, two systems.” The idea of holding democratic, popular elections to choose the chief executive was written into the city’s Basic Law, and a goal of 2017 was set. But it also was described as the “ultimate aim,” signaling it wasn’t set in stone. When the government presented its election plan in 2014, the “ Occupy Central” protests erupted, with tens of thousands of student activists and their supporters blocking major roads for 79 days. They were enraged that candidates would have to be pre-screened by an election committee dominated by Beijing loyalists. Hong Kong’s legislature rejected the plan in 2015 and the process stalled there. In 2017 the same committee handed Lam an easy victory, with no popular vote. In other signs of China’s growing assertiveness, six winners were disqualified after the 2016 legislative elections, which had generated a surge in support for pro-democracy candidates; prominent activists and student leaders were prohibited from running for office; and a pro-independence party was banned entirely. Chinese President Xi Jinping has said that challenges to Beijing’s rule in Hong Kong won’t be tolerated.

The Argument

The massive opposition to the extradition bill — and repeated demands for more democracy — illustrate the breadth of public concern about preserving Hong Kong’s unique character. Serious erosion of the city’s autonomy also could jeopardize the special trading status under American law that Hong Kong has long enjoyed — and that has helped it prosper. Pro-Beijing groups argue that China never promised more than the limited voting system in place, that extradition is needed to prevent Hong Kong from becoming a criminal haven, and that repeated scenes of mayhem on the streets damage the city by undermining the stability and rule of law essential for a global financial hub. China’s aversion to Hong Kong’s democracy movement is entwined with its claim to have redressed past national humiliation by regaining the city from the British, who took control in 1841 after the First Opium War. To lose control of it now would so undermine the Communist Party’s credibility as to make such a scenario unacceptable.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on China's handling of Hong Kong 20 years after the handover, how it keeps loyalists in the city’s top job, and the countdown to 2047.

- Bloomberg Opinion columnists look at Hong Kong’s economic divide, the NBA flap and how today’s China needs to be more Chinese.

- The Hinrich Foundation on why Hong Kong’s autonomy is important for trade.

- China presented its interpretation of Hong Kong democracy in a 2014 policy paper (in Chinese).

- The website of the pro-democracy group Hong Kong 2020 sets forth objections to the way Hong Kong chooses its chief executive and suggests improvements.

- A Bloomberg photo essay on the 79-day Occupy Central demonstrations, and on how umbrellas were used again in 2019.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Grant Clark at gclark@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.