The Opioid Crisis

Heroin and Opioids

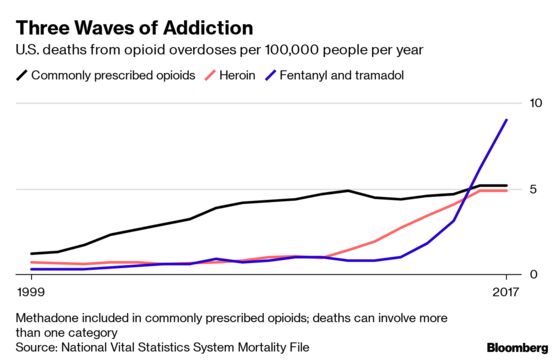

(Bloomberg) -- Two decades ago, a new generation of supposedly safer painkillers triggered an epidemic of opioid abuse in the U.S. Since then, opioid overdoses have killed well over 400,000 Americans — more deaths than the country’s military suffered in World War II. The surge in prescription drug abuse was followed by a wave of heroin addiction. Now, more than half of opioid deaths are caused by synthetic versions such as fentanyl, a chemical powerful enough to kill in tiny concentrations. Beyond the death toll, at least 2 million Americans have become addicted.

The Situation

U.S. deaths from opioid overdoses reached a record high of 47,600 in 2017 but may have leveled off in early 2018, according to preliminary data. Some steps to curb the epidemic may be bearing fruit, while others are just getting underway:

○ China in May closed a loophole that had hindered efforts to crack down on the laboratories that have made it the world’s largest exporter of fentanyl.

○ The U.S. National Institutes of Health is launching a $350 million study to see if opioid deaths can be cut by 40% by improving access to medications such as buprenorphine and methadone that reduce drug cravings.

○ After peaking in 2012, the number of opioid prescriptions fell 28% by 2017. Even so, in 16% of U.S. counties, enough opioid prescriptions were dispensed for every resident to be given one.

○ States have expanded access to the opioid antidote naloxone, in some cases requiring doctors to “co-prescribe” it for patients receiving legal opioids who are considered at high risk of overdosing.

○ The founder of Insys Therapeutics Inc. was convicted of conspiring to bribe doctors to increase opioid sales. The company agreed to pay $225 million to settle federal charges while filing for bankruptcy.

○ More than 1,600 lawsuits accusing some of the world’s most profitable drugmakers of creating the public-health crisis have been consolidated into a single federal case. In the first case to go to trial, an Oklahoma judge ruled that Johnson & Johnson must pay the state $572 million for duping doctors into overprescribing its opioid-based medications. Oklahoma had sought up to $17.5 billion; it had earlier reached a $270 million settlement with OxyContin-maker Purdue Pharma LP and the billionaire Sackler family that controls it.

The Background

Extracts of the poppy plant have long been a source of trouble. In the 19th century Opium Wars, Britain forced China to allow the opium trade. Heroin, first produced in 1898 by Bayer, the German pharmaceutical company, was marketed as a non-addictive substitute for morphine. The current crisis has unfolded in three waves, U.S. health officials say. The backdrop for its start was a long-standing debate over whether patients were being undertreated for pain because of doctors’ fears about addiction. Then, in 1996, Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin as a safer alternative. By 2001 its annual sales had surged to $1 billion. In 2007, Purdue paid $600 million in fines for misbranding the product as less addictive than other painkillers. In 2010 it released a reformulated version that was harder to crush for snorting. Some of those addicted to legal painkillers began turning to heroin, triggering a surge in its use. More recently, dealers have been lacing heroin with synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and tramadol for a stronger high. While the biggest increases in addiction in the epidemic’s first two waves were found among whites, fentanyl has driven deaths up most sharply in black and Hispanic communities. In Canada, fentanyl has increased the overdose rate in Vancouver to match those found in the worst-hit areas in the U.S. Fentanyl deaths have risen sharply in the U.K., but from a far lower base.

The Argument

In 2017, President Donald Trump declared opioid abuse a public health emergency, and the budget for dealing with it roughly doubled to about $7.4 billion. In his speeches, however, Trump has focused on cutting off the supply of drugs. Health experts have stressed the need for more treatment. According to the NIH, only about a fifth of people who need treatment for opioid addiction get it, and far fewer receive the most effective medications for long enough. The agency is funding programs in 60 communities to test the idea that tying doctors, hospitals, schools, police departments and correctional facilities together to deliver treatment can prevent many deaths. One hurdle is a shortage of physicians trained in prescribing buprenorphine or methadone or in treating addiction. Many U.S. states, which end up covering much of the cost of the crisis, are pinning their hopes on winning a big legal settlement with drugmakers like the one cigarette makers agreed to in 1999. That paid $246 billion to cover costs related to smoking. Some groups are trying to pressure drug companies by shaming those seen as to blame for the crisis: In response to protests, museums including New York’s Guggenheim and London’s Tate have renounced money from the Sackler family, who have been prominent supporters of the arts. Meanwhile, groups that advocate for patients in chronic pain worry that the steps taken to limit prescriptions are reducing access for those who need the drugs most.

The Reference Shelf

- A Journal of the American Medical Association article analyzing 50 years of heroin use.

- Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

- The Drug Enforcement Administration’s threat assessment for 2018.

- A Cincinnati Enquirer series on “ Seven Days of Heroin.”

- A Bloomberg News article on surgeons working to reduce the use of painkillers by their patients.

- A seven-point plan for fighting the epidemic outlined in a column by Michael R. Bloomberg, the founder and majority owner of Bloomberg LP, the parent company of Bloomberg News.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: John O'Neil at joneil18@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.