Focused on 10-Year Yields? Traders Yes, the Fed No

Focused on 10-Year Yields? Traders Yes, the Fed No

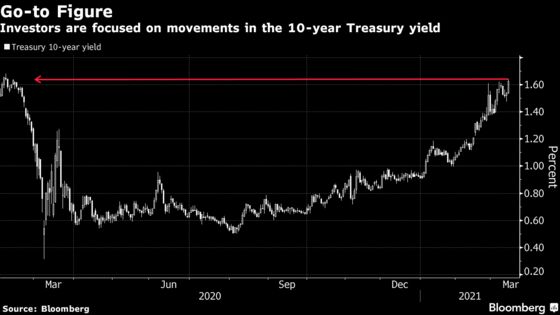

(Bloomberg) -- Financial news is always awash in numbers, but there’s one figure that seems to be getting more attention than anything else: the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury notes. Not only are investors laser-focused on it, but gyrations in other asset classes have been driven by its movements this year. Increases that reach market milestones could have big implications for everything from U.S. stock prices to the value of emerging-market securities -- even though Fed Chairman Jerome Powell says he sees no reason for the central bank to push back against a surge in Treasury yields. Still, some observers are speculating that the yield’s sharp rise in 2021 may mark a sea change in the era of historically low rates and inflation.

1. Why do investors care about Treasury yields?

Treasuries -- debt issued by the U.S. government -- are widely regarded as the world’s safest securities, and the $21 trillion Treasuries market forms the bedrock of global finance. Investors care about the prices at which Treasury notes and bonds change hands, but it’s their yields -- broadly speaking, the total annualized rate of return for buy-and-hold investors -- that are more telling. That’s because they show the interest rate the government has to pay to borrow for different lengths of time. They also provide a benchmark for other borrowers, like companies and homeowners with mortgages.

2. Why is the 10-year yield so important?

Treasuries are issued in a range of maturities, from a few days to 30 years, and investors are keenly attuned to rates across the so-called yield curve. But the curve’s various segments -- and the gaps between them -- can indicate quite different things. Short-term rates, for example, are heavily influenced by the choices of the U.S. Federal Reserve, which has said it plans to keep its policy rate locked near zero for several years. Long-term yields, on the other hand, have more freedom to move, making them barometers of investors’ outlook for economic growth and inflation. With very long bonds, like 30-year issues, uncertainties are greater, so many focus their attention around the 10-year security instead. The result is that the 10-year note is one of the world’s most important benchmarks for the cost of risk-free borrowing and its rate is used to price trillions worth of other securities.

3. Is there one key yield level that matters most?

Yes and no. The 10-year yield hovered around 1.73% in mid-March, up from less than 1% at the start of 2021 and as little at 0.31% during the market turmoil of March 2020. Around 2% -- give or take -- is a hot forecast for the end of the year. As the yield keeps inching higher, some are warning it will set off triggers for a round of so-called convexity hedging, a practice related to holdings of mortgage debt that can amplify swings in yield levels. The increase in yields over the past year -- with the 10-year up over a percentage point -- has already put it above the dividend yield on the S&P 500.

4. What does the Fed think about the increase in yields?

Even as yields have charged higher and traders see the Fed lifting rates well before officials have signaled they would, the Fed insists its monetary policy is appropriate and will remain accommodative for years to fight the pandemic’s long-term damage. Powell has acknowledged that the run-up in bond yields was “notable,” yet has made clear that he would only be concerned about the rise if it were accompanied by “disorderly conditions in markets or by persistent tightening of financial conditions that threaten the achievement of our goals.”

5. When happens if the markets and the Fed disagree?

Sometimes the Fed has been right, but on other occasions the market has been more accurate. Back in 2014, for example, central bank officials signaled that the pace of growth and inflation would warrant aggressive monetary policy tightening over the coming years. Fixed-income traders said that was way off, a forecast that proved more accurate, with the central bank going on to lift rates just once in 2015 and once in 2016 -- much closer to what the market had predicted. Analysis by strategists at JPMorgan Chase & Co. has led them to declare that “markets have a long history of prematurely anticipating Fed rate hikes.” And the team thinks sometime in the future traders will scale back how soon they foresee the first Fed rate increase -- to closer in line with where Fed officials now indicate.

6. How does the 10-year yield affect other assets?

All returns are relative: Investors weigh choices not in the abstract, but in comparison to the risks and rewards offered by other assets. The 10-year Treasury yield is a handy yardstick against which investors can compare possible returns or losses on riskier assets, such as stocks or corporate loans. A rise in the 10-year yield can therefore be bad for stocks, because investors may have less to gain from taking on more risk. It can also undermine stock prices by delivering a hit to discounted values of company cash flows. That’s especially true for growth stocks -- heavily represented by tech firms -- given that much of their income streams are expected well in the future.

7. Has the 10-year always been so important?

In decades past, all eyes used to be on entirely different indicators, like central bank money supply numbers, to divine the path of Fed policy. The central bank regime that underpinned that kind of analysis has long since shifted. In more recent years, traders have keenly watched quarterly projections by Fed officials for the bank’s policy setting rate, known as the Fed funds rate, for the next few years. They also look at the signals being sent by money-market derivatives, including Eurodollar futures and overnight index swaps, that show traders already penciling in the start of the next tightening cycle. But with investors around the world trying to assess growth and inflation risks, the focus on the 10-year has become that much more acute.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on the yield curve and negative convexity.

- QuickTakes on central bank interventions during the pandemic and on a renewed debate over inflation.

- A Bloomberg Opinion column on Powell and increased 10-year Treasury yields.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.