Europe’s Banking Union

Europe’s Banking Union

(Bloomberg) -- Back in 2012, European leaders emerged from an all-night summit resolved to “break the vicious circle” between national governments and the banks that held their bonds — the so-called doom loop. With the debt crisis raging for a third year and Spain’s banks on the ropes, they put forth a plan for a banking union, focused on the euro currency bloc, that would keep taxpayers off the hook when lenders collapse. The project had three parts: putting the European Central Bank in charge of bank supervision; setting up a single resolution authority to handle failing lenders; and creating a common system of deposit insurance. Seven years later, the first part was well established and the second had come through its first big tests. Work on the third is still mired in political disputes, though signs of potential compromise emerged in late 2019. Nevertheless, European banks are still closely linked to their home countries.

The Situation

The lack of a common deposit insurance scheme, long cited as a roadblock to cross-border bank consolidation, was put back on the table in late 2019 when German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz signaled a softening of his country’s longstanding opposition. Meanwhile, the Brussels-based Single Resolution Board, responsible for handling euro-area bank failures, has been open for business since 2016. While it has dealt with the collapse of a Spanish bank, rules that can force senior bondholders to take losses have yet to be tested. The agency is setting the level of debt that banks in the European Union must have available to be wiped out or converted into equity if they get into trouble. The biggest banks in the region will eventually need to have about 8% of their liabilities and shareholder equity in such securities. At the same time, the Frankfurt-based ECB is developing a track record as a banking supervisor, after kicking off its oversight in November 2014 with a stress test that failed 25 lenders. There are mounting concerns about the low profitability of European banks — especially due to negative interest rates — and the continued fragmentation of the market along national lines.

The Background

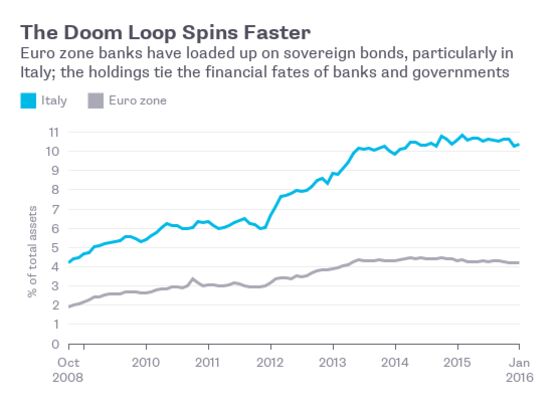

The banking union was born in the heat of Europe’s financial meltdown, part of a policy push that included more than 40 laws to curb banks’ risk-taking and enforce market discipline. Unlike the U.S., with its single central bank and strong nationwide regulators, the EU had to build institutions from scratch at the same time it was putting out fires with bailouts for Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Cyprus. The links between banks and sovereigns were evident in both directions during the crisis: Greece’s budget blowout crippled its lenders through their holdings of the government’s debt, while weak banks forced Ireland into a bailout and threatened the finances of Spain. The EU put up more than 4.5 trillion euros ($5 trillion) — 37 percent of the bloc’s economic output — in rescue aid for banks in the three years to October 2011. There’s little evidence yet that the doom loop has been broken. Banks in the euro area have barely reduced their holdings of bonds issued by their home governments. While those made up 3.5% of their balance sheets in mid-2012, that share continued to climb to more than 4%, before falling to 3.2% at the end of September 2019.

The Argument

The bloc is deeply divided over the remaining roadblocks to completing the banking union. The more fiscally conservative countries want banks in southern Europe to reduce their soured loans before sharing more responsibility through common deposit insurance. The debate over sovereign debt, which is currently treated as a risk-free asset on bank balance sheets, also rages on. It’s tricky to unwind the links between national governments and their financial sector, both because of the sheer amount of state debt on banks’ books, and because of the role the bonds play in financial plumbing, such as repurchase agreements. Policy makers in Brussels and at the ECB also want to make it more attractive for banks to expand and merge across borders, which would make them less dependent on their home states. Bankers blame continued distrust between countries for holding up these efforts.

The Reference Shelf

- A Bloomberg News article and a timeline tracing the events leading to Europe’s banking union.

- The European Commission’s website has information on the proposed banking union and crisis management.

- The ECB’s plans for banking supervision.

- A February 2013 International Monetary Fund report on the EU’s banking union plan.

- QuickTakes on stress tests, zombie banks and the euro crisis.

— Patrick Henry contributed to an earlier version of this QuickTake.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Leah Harrison at lharrison@bloomberg.net, Andy Reinhardt

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.