Earthquake Readiness

Earthquake Readiness

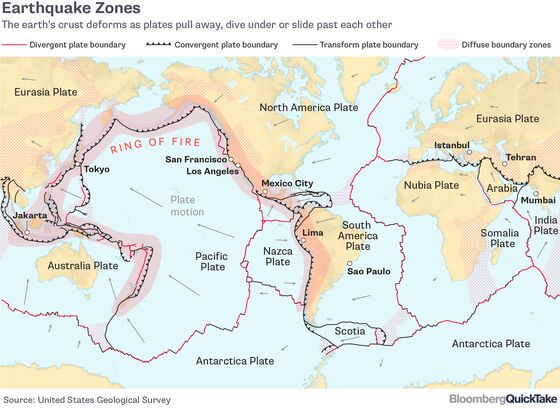

(Bloomberg) -- At least half of the world’s largest cities are considered at moderate or high risk of a major earthquake. Fears of the next “Big One” affect such major population centers as Tokyo, Mumbai, Jakarta, Mexico City, Manila, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sao Paulo, Istanbul and Tehran. With the world becoming ever-more urbanized — it’s projected that almost two-thirds of the population will live in cities by 2050 — earthquake preparation is a massive long-term challenge thrust into the hands of short-term elected leaders. What steps should be taken today to protect people, companies and the economy from a threat so remote that it could strike once in a lifetime, if that?

The Situation

While cities differ greatly in their preparations, many in fault zones are moving more urgently to revisit disaster plans in the wake of Japan’s harrowing 2011 Tohoku earthquake, which spawned a tsunami that triggered a nuclear meltdown and killed more than 15,000 people. California Governor Gavin Newsom said back-to-back earthquakes in July, among the strongest to shake California in decades, were “a wake-up call” for his state’s residents and government. Even before those quakes, Los Angeles was requiring owners of about 13,500 wood-frame and 1,500 brittle concrete buildings to strengthen them, and San Francisco had ordered retrofits of wood-frame apartment buildings that house a total of more than 115,000 people. Newsom said California’s piece of a multistate early-warning system — which could alert people to seek safety and automatically shut down vulnerable industrial and transportation moments before the ground beneath them starts moving — is 70% installed. The system is supposed to be ready statewide by the end of this year and in Oregon and Washington in 2021. Japan, Taiwan, Italy and Mexico are among the earliest adapters of such warning systems, which detect the first waves of a quake and enable rapid alerts via broadcast media and text messages to mobile phones. Improvements to Mexico City’s schools and other public buildings after a catastrophic 1985 quake meant fewer deaths in a September 2017 earthquake, though it still killed almost 400 people.

The Background

Shaking is a fact of life. Earth experiences several hundred observable earthquakes daily, with a major one — magnitude 7 or greater — happening more than once per month on average. There even are so-called induced tremors, or small quakes caused by oil extraction and other human activities. Coastal cities in the seismically hyperactive “Ring of Fire,” including Tokyo, Jakarta and San Francisco, share not just proximity to fault lines and volcanoes but a soft and saturated soil that can amplify the destruction of a quake’s shakes. Seismologists were startled that the 1985 earthquake caused more than 5,000 deaths in and around Mexico City even though its epicenter was more than 200 miles (320 kilometers) away. Although scientists say major earthquakes are not increasing in frequency, the potential for damage is bound to rise when cities grow taller, denser and richer. There are 283 million people in metropolitan areas at some risk of being killed, hurt or evacuated due to an earthquake, according to global reinsurer Swiss Re.

The Argument

Retrofitting cities that date back hundreds of years isn’t cheap or painless. The benefits are largely theoretical, the cost to stretched budgets is tangible and progress can seem excruciatingly slow. Los Angeles is giving owners of potentially at-risk buildings as long as 25 years to make improvements. San Francisco is letting its skyline grow taller and denser despite lingering doubt that high-rise buildings can be made quake-proof — and even though one of the city’s skyscrapers is sinking and leaning. In India, efforts to improve engineering and building code enforcement have mostly languished, leading one expert to lament the lack of “champions for seismic safety.” There’s worry as well in Turkey, where the government is criticized for undoing some earthquake-preparation measures it pledged after a 1999 quake killed at least 17,000 people, and in Peru, where the capital city of Lima has a perilous combination of unsteady housing built atop unstable soil and the national civil-defense institute holds earthquake evacuation drills. All that may explain the move toward early-warning systems, which could give people a tiny window — perhaps just seconds, but conceivably a minute or more — to evacuate buildings. Technology may provide cheaper ways to warn those at risk: U.S. researchers are exploring how to employ the motion sensitivity and ubiquity of smartphones to create a massive network that would automatically detect earthquakes and issue near-instantaneous warnings.

The Reference Shelf

- Swiss Re’s global ranking of cities under threat from natural disasters.

- A hard look at earthquake safety in India.

- Los Angeles is racing to fix vulnerable buildings.

- The New York Times examines San Francisco’s gamble on high-rise buildings.

- The New Yorker on “The Big One.”

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Laurence Arnold at larnold4@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.