Vaping

Vaping

(Bloomberg) -- As cigarette smoking declines worldwide, tobacco companies have turned to a new product line to make up for lost revenue: vaping devices. Using an e-cigarette, vapers get a hit of stimulating nicotine without resorting to a burning stick of tobacco. These products are marketed as less risky alternatives to cigarettes, and some studies show they are, although there isn’t enough long-term data to make a definitive conclusion. Also, they may not be harmless, and some research suggests they lead young users to try traditional cigarettes. Consequently, vaping has provoked one of the most robust debates among public-health specialists in years. Some are pushing for curbs where they don’t already exist, out of safety concerns and fear the popularity of the devices will slow gains in the war on smoking. Others see vaping products as a valuable tool to help smokers quit, and thus as a means for accelerating that fight.

The Situation

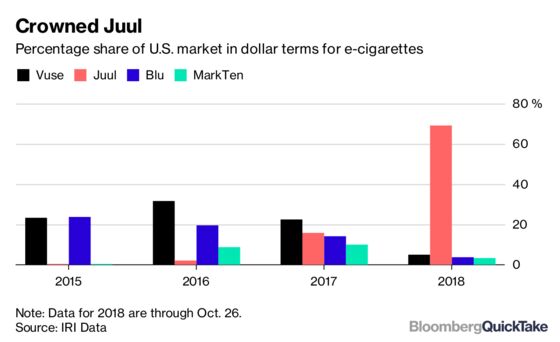

Declaring that the U.S. was experiencing an epidemic of teen vaping, the nation’s Food and Drug Administration in November announced plans to tighten regulations on e-cigarettes. Officials said vaping among high-schoolers rose 75% from 2017 to 2018, according to preliminary data. That meant that about 20% of the students were indulging. A single product accounts for much of the boom: the Juul e-cigarette. Created by two product designers who were ex-smokers, the Juul is sleek, so it looks cool, and it’s tiny, enabling the young user to palm it and discreetly take a hit when a teacher (or parent) isn’t looking. And, like many other vaping devices, its refills come in tasty flavors such as mango and mint. The FDA said it planned to limit sales of most types of flavored e-cigarettes to vaping stores and online retailers who verify a purchaser is 18 or older, restrictions Juul’s maker voluntarily adopted in the meantime. Of about 80 countries that regulate e-cigarettes, 29 — including Brazil, Greece, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Thailand — ban their sale altogether. Worldwide, the market for vaping products was estimated at about $11.5 billion in 2018 and is growing rapidly.

The Background

A Chinese pharmacist and smoker named Hon Lik gets credit for developing the e-cigarette in 2003. It appeared in the U.S. and Europe by 2006. Today, vaping products take many forms and deliver varying levels of nicotine, an alkaloid present in tobacco that is addictive. Early versions looked like regular cigarettes or were housed in metallic tubes. More recent models are more like fat pens. The Juul resembles a USB flash drive. Inside an e-cigarette, a battery heats a liquid spiked with nicotine, producing a vapor the user inhales. There’s no burning tobacco and thus no smoke or tar. A related line of products, so-called heat-not-burn devices, contain tobacco that emits a vapor while being heated to significantly less than the temperature at which a regular cigarette combusts.

The Argument

The evidence so far suggests that vaping is a safer choice than lighting up. A 2016 scientific paper examining 22 studies concluded that exclusive use of vaping devices produces just 5% of the mortality risks associated with smoking. But even if the products help people stop smoking, one concern is that they’ll never give up vaping and so would have been better off quitting another way. Another worry: As the practice becomes increasingly common, it will attract more people who never would have smoked. A 2018 review of 800 studies conducted by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine found “no evidence whether or not e-cigarette use is associated with long-term health effects,” but the practice is too new for there to be significant data. It’s plausible, yet not proven, that e-cigarette aerosols can damage tissue and cause disease, including cancer. The effects on humans of nicotine are not well-studied, although adolescents appear to be particularly vulnerable to it, with some evidence suggesting it can harm brain development. The National Academies’ review found substantial evidence that young vapers are more likely than non-vapers to try regular cigarettes. However, a review of studies commissioned by Public Health England concluded that it hasn’t been established that they become regular smokers.

The Reference Shelf

- The review of vaping studies by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine and another commissioned by Public Health England.

- The FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products’ website gives its position on e-cigarettes.

- The Public Health Law Center's interactive map shows e-cigarette regulation in each U.S. state.

- A Bloomberg editorial on the dangers of vaping.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Lisa Beyer at lbeyer3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.