Sport, Drugs and Cheating

Doping

(Bloomberg) -- If a pill or injection could make you the best in your field, would you take it? Even if that was cheating and might damage your health? For the likes of Lance Armstrong and Ben Johnson, and — apparently — Russia's Ministry of Sports, the answer was “bring it on.” The temptation is only heightened when state-of-the-art stimulants are undetectable in the latest drug tests. But the advantage in this long-running cat-and-mouse game may be swinging back toward anti-doping authorities, thanks to the prolonged storage of test samples. That’s allowed specimens to be reanalyzed using newer technologies, resulting in the nabbing of dozens of abusers who thought they had gotten away with it. Combine that threat with the ever-present risk from whistle-blowers, and drug cheats may rest a little less easy.

The Situation

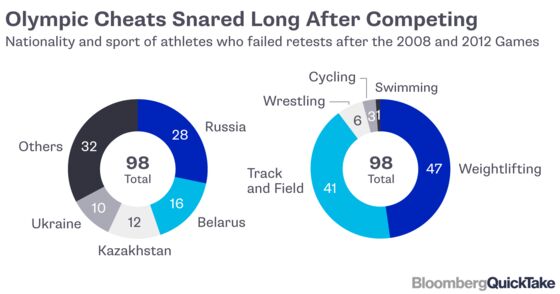

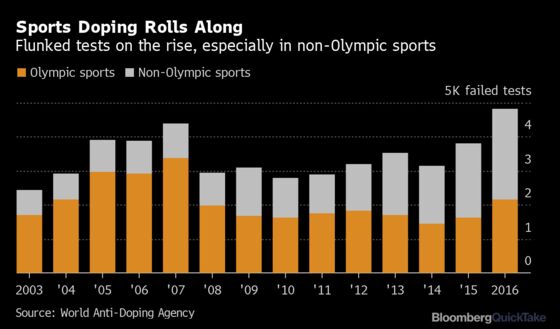

Russia was barred from the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar— the latest punishments for a doping program that climaxed at the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics in Russia. Officials there were accused of fabricating evidence to cover up the use of banned substances by the country’s athletes. The four-year international sports ban, imposed in December by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), also stands to rule Russia out of the 2020 European Championships and the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. As happened at the 2018 Winter Games, individual Russian athletes who comply with strict conditions will be allowed to compete under a neutral flag. Since placing first in the medals table in Sochi, Russia has been stripped of 13 of its 33 medals as the scale of its doping program emerged. An independent investigation commissioned by WADA found that Russian sports officials oversaw a vast program to manipulate doping test results from 2011 to 2015, and that athletes’ positive urine samples were swapped out during the Sochi Olympics. Allegations of Russian state-sponsored doping were first leveled in 2016 by a whistle-blower who ran the Moscow laboratory responsible for Olympic drug testing. The latest four-year ban follows the discovery by experts of anomalies in drug test results recovered from a Moscow laboratory in January, under an agreement in September 2018 to lift a previous three-year ban. Separately, Russia’s track and field team was barred from the 2016 Rio Olympics following revelations by a whistle-blowing runner. Russian President Vladimir Putin labeled the athlete “Judas” and has described the allegations of state-directed doping as a U.S. conspiracy. The analysis of stored samples is becoming an increasingly effective backup for anti-doping authorities: Close to 100 athletes — including at least 40 medalists — were snared using samples from the 2008 Beijing and 2012 London Summer Olympics. Among the guilty parties, track and field, weightlifting and Russians dominated. But in a setback for the anti-doping movement, the highest sports court in 2018 overturned 28 life bans for Russian athletes, imposed by the Olympic authorities after forensic analysis of samples stored from the Sochi Games.

The Background

Athletes for centuries have sought a chemical edge. The ancient Greeks used alcoholic concoctions and hallucinogenic mushrooms. Taking stimulants was an accepted practice when Thomas Hicks won the 1904 Olympic marathon race — and almost died — after a mixture of brandy and strychnine got him to the finish line. Within a decade, Austrian horses had tested positive (cocaine and heroin were commonly administered) in some of the earliest incidents of illegal doping. The Olympics began prohibiting drug-taking in the 1960s but has long struggled to keep up with the dopers. The most popular methods have included blood doping (via injections of the hormone EPO or blood transfusions) and taking anabolic steroids or human growth hormone. Cycling, baseball and track and field have experienced decades of scandals and high-profile tumbles from grace. The doping Hall of Fame includes the likes of Major League Baseball’s Alex Rodriguez, cyclist Lance Armstrong and sprinters Ben Johnson and Marion Jones. State-sponsored doping programs are nothing new; the East German swimming team that dominated the 1976 Olympics later sued the government for feeding athletes anabolic steroids.

The Argument

Critics of the existing system maintain that the crusade against doping has failed. One study, based on anonymous surveys, concluded that drug use is widespread among elite athletes. And the anti-doping agency missed the Russian conspiracy entirely until a whistle-blower stepped forward. Some support a doping free-for-all for substances that do not pose health risks. That, opponents say, would reduce sports to a competition about taking the best stimulants and would have worrying implications for youth and amateur sports. They note a catalogue of suspicious deaths possibly related to performance-enhancing drugs. A survey from the 1980s revealed that most elite athletes would take a drug that guaranteed success but killed them within five years. A 2012 poll posing the same question (the Goldman dilemma) yielded a result of about 1 percent. Anti-doping enforcers say drug-taking will never be eradicated but that they need additional investigatory powers and financial support to keep notching small victories. According to Dick Pound, the former long-serving head of the World Anti-Doping Agency, sports remains in “a state of catatonic and unpersuasive denial” and too many people involved do not want the anti-doping system to work.

The Reference Shelf

- The Netflix documentary, Icarus, centers on the Russian scientist-turned-whistle-blower whose allegations spurred the McLaren report.

- After losing to drug cheats, athletes get their medals.

- World Anti-Doping Agency’s statistics and list of banned substances.

- The McLaren Report into Russian doping, a Bloomberg summary and the second McLaren Report.

- The man fighting to salvage Russian sport’s reputation.

- Lance Armstrong confesses to doping on the Oprah Show.

- The New York Times looks at performance-enhancing drugs in amateur sports: In Chase for Wins, a Runner Cheats.

- A British Journal of Sports Medicine makes the case for allowing performance-enhancing drugs in sports.

- The Mitchell Report into doping in baseball.

- A New York Times story on Russian state-sponsored doping.

Tariq Panja contributed to an earlier version of this article.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.