Did Europe Just Agree to Joint Borrowing? Not Exactly

Did Europe Just Agree to Joint Borrowing? Not Exactly

(Bloomberg) -- Faced with an unprecedented recession, the European Union is considering a game-changing way to fund recoveries in the nations hit hardest by the pandemic: Issuing debt on behalf of all 27 EU members. Even though the proposal doesn’t involve full mutualization of debt, and still needs the backing of some skeptical nations, it marks rarely seen ambition from the bloc -- and at a time when it’s needed most.

1. What is the plan?

The EU’s initial response to the crisis came mainly in the form of making cheap loans available, a strategy that countries in the south argued would only increase their debt burden and weigh on future economic growth. In response, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron championed a 500 billion-euro ($550 billion) aid package financed through the issuance of bonds by the commission -- the EU’s executive arm -- on behalf of the EU as a whole. Proceeds would be distributed to countries most affected by the crisis in the form of grants. Repayments would come from the EU budget, where Germany contributes the lion’s share. The proposal marked a dramatic shift for Germany, which initially opposed any form of mutualized borrowing.

2. Will the plan be accepted?

It moved a step closer after the commission announced its proposal for a recovery fund consisting of 500 billion euros to be distributed in the form of grants (as per the French and German plan) as well as up to 250 billion euros in loans. To fund the package, the EU would borrow up to 750 billion euros on financial markets. Italy, for instance, stands to receive 82 billion euros in grants and as much as 91 billion euros in low-interest loans, according to an official familiar with the matter. The package needs unanimous approval from the 27 EU governments, whose leaders will meet June 19.

3. Will there be objections?

Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden have signaled their resistance to handing out too much money as grants and said they will look closely at the conditions attached to any aid. As net donors to the EU budget, the so-called Frugal Four are skeptical of a major borrowing spree that could leave their taxpayers on the hook for decades to come. Also, Eastern EU members are worried that they will lose out since repayments will come from the budget.

4. What’s at stake?

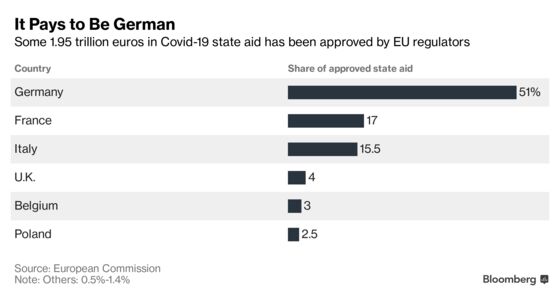

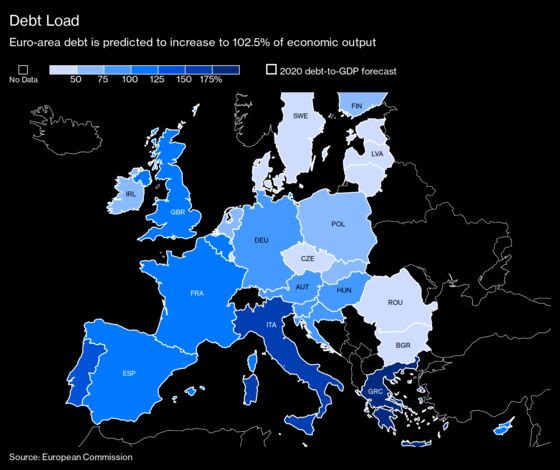

Broadly speaking, southern European countries, most notably Italy and Spain, have been the hardest hit by the coronavirus. These are also the nations that came into the crisis with weaker economies and higher levels of debt and unemployment. The commission has warned that the unevenness of contractions and recoveries will deepen divisions within the bloc and could put at risk stability in the euro area, whose 19 members share the common currency. Deep-pocketed member states such as Germany have showered their firms with state aid, while others such as debt-addled Italy can’t match that spending power. That is distorting the level-playing field between companies in the EU’s vast single-market. Social discontent could destabilize governments and fuel anti-European sentiment in countries that are struggling the most. In short, the EU’s future is at stake.

5. Why is joint action so hard?

The EU is not a country. It doesn’t have a common treasury that’s expected to support regions in need, the way the U.S. Treasury pours funds to states hit by hurricanes. Nor does it have anywhere near sufficient funds in its relatively meager common budget to deal with a crisis on this scale. Even in the euro-using core, the monetary union is not backed by real economic or banking unions. As the EU’s devastating debt crisis of 2010 showed, in tough times money tends to fly to the continent’s safe harbors, exacerbating liquidity crunches in the economically weaker countries as their borrowing costs surge.

6. What else was on the table?

During the debt crisis, countries in the bloc’s south proposed what they called eurobonds, in which member states would pool their borrowing power and spread the burden of additional debt. The idea was that by issuing jointly backed debt, the financial solidity of countries like Germany and the Netherlands would allow all countries to borrow more cheaply, and dispel doubts about the sustainability of weaker members’ finances. This year, that idea was revived in proposals for what have been termed coronabonds, but was quashed by a group of richer, northern leaders who refused to put their taxpayers on the hook for the liabilities of their southern neighbors.

7. How is the Franco-German plan different?

Germany says the recovery fund does not represent debt mutualization. First of all, it’s a one-off concession for the duration of the crisis. Second, if coronabonds were issued, the danger for Merkel could be like that faced by someone who signed a lease when a roommate can’t pay their share of the rent -- Germany could be on the hook for a bigger chunk than it expected. But in the Merkel-Macron plan, Germany wouldn’t be liable for the entire 500 billion envelope, only for its share of the budget, an amount that corresponds to its share of EU economic output. On the other hand, Germany is the main contributor to the EU budget, so it will repay most of the funds, whatever the debt instruments are called. “The Franco-German deal is a real step towards creating the first meaningful EU debt,” said Guntram Wolff, director of the Brussels-based Bruegel think tank.

8. Is this even allowed?

Debt mutualization is not. Article 125 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union says that neither the EU nor individual member states can be liable for the debts of other governments. A so-called “Hamilton moment” -- as happened in the U.S. in 1790 -- whereby obligations across the 27-nation bloc are mutualized would require treaty changes adopted by national parliaments and in some cases referendums. So far, there’s no sign of majority backing for reform that would cede national sovereignty by giving a central authority the power to raise taxes and decide how money is spent throughout the EU or even the euro area.

9. But doesn’t this come close?

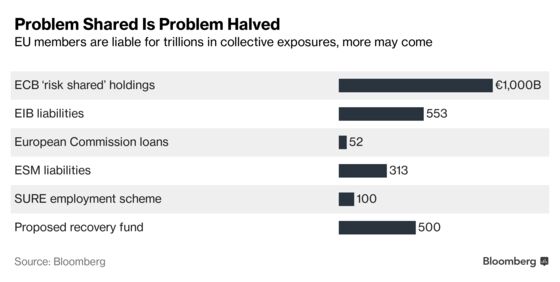

In practice, the bloc’s members are progressively sharing increasing levels of risk and have bailed each other out in times of need. For example, the European Stability Mechanism -- the euro area’s crisis fund -- has raised hundreds of billions on debt markets, which it then lent to Greece on terms normally reserved for countries with AAA credit rating, allowing the EU’s most indebted state to make billions in savings from interest payments. The same arrangement is also available now for countries wishing to draw up to 240 billion euros from the fund to finance costs related to the pandemic. Also, the European Central Bank has been buying massive amounts of debt under its bond-buying programs. While much of that is held by national central banks, a good chunk is on the ECB’s own books, making its shareholders -- euro-area members -- in theory liable for any losses.

10. So it’s the form of the borrowing that matters?

In a way. The EU, through the commission, has long been able to borrow, as have other European institutions. This ability rests on the backing and commitment of member governments to the EU project. All European institutions have a stellar credit rating, on the assumption of such backing from the richer Northern European nations. In essence, these nations lend their fiscal muscle to the EU, allowing its institutions to carry out transactions on concessional terms for the benefit of weaker members. It may not be debt mutualization, but it’s European solidarity in practice.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on the EU’s existential threat and coronabonds.

- What the world’s coronavirus fighters can learn from the Greek debt crisis.

- Can the EU seize its “Hamilton moment?” asks Bloomberg Opinion’s Ferdinando Giugliano. Fellow columnist Andreas Kluth says the proposal marks a “dramatic change.”

- The Franco-German proposal.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.