Deadly Pig Disease Sparks Fear of a Heart Drug Shortage

Deadly Pig Disease Sparks Fear of a Heart Drug Shortage

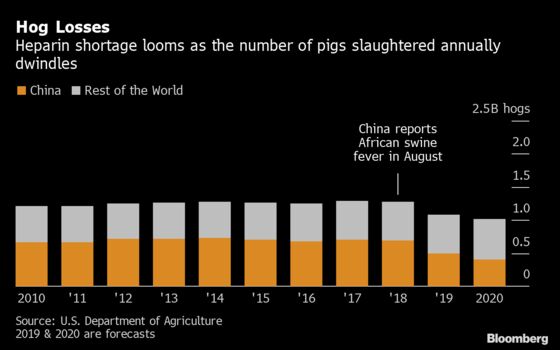

(Bloomberg) -- With African swine fever wiping out a quarter of the world’s pigs, primarily in China, doctors and drugmakers around the world are sounding the alarm about a possible prolonged shortage of heparin, a critically important blood thinner. The drug, derived from pig intestines, is widely used to treat heart attacks and prevent deadly blood clots. China has been the primary source of the medicine, and the crisis there highlights a need to develop alternate supplies.

1. What is heparin?

Heparin is a naturally derived, sugar-based molecule that’s administered by injection or infusion to prevent blood from coagulating and causing vessel-blocking clots that can starve organs of critical oxygen. Discovered more than a century ago, today some 10 million to 12 million people in the U.S. alone are treated with heparin each year, with the drug’s global sales exceeding 200 tons, or $5 billion, annually. A dose though is inexpensive, costing less than a packet of bandages.

2. Why is it important?

It’s routinely prescribed for heart attack patients with clogged arteries, patients undergoing major orthopedic and cardiac surgery, and patients with a central venous catheter or receiving a blood transfusion. Recipients of certain life-saving treatments such as blood-cleaning kidney dialysis or mechanical heart and lung support receive it, as do patients who are immobile for long periods. Heparin is often used to coat materials such as coronary stents that are in contact with blood. It’s the preferred anticoagulant for hospitalized patients because it works rapidly, can be carefully administered and there’s an effective antidote for it: protamine sulfate. A study by the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne found as many as 15% of patients are exposed to heparin in some form on a daily basis.

3. What’s the concern?

Researchers are warning of an “imminent risk” of a global shortage because of the unprecedented scale of the cull. Most heparin-based drugs are sourced from the intestinal lining of slaughtered pigs. About 60% to 80% of the active key ingredient is prepared by companies in China and formulated into ready-to-use drugs by pharmaceutical companies around the world. China, home to half the planet’s pigs, is the only country that can meet the global demand for the raw material. The World Health Organization recommends governments stockpile heparin as an essential medicine.

4. What’s the supply like now?

A U.S. congressional committee asked the Food and Drug Administration in July to monitor heparin supplies, noting a six-to-nine-month lag time before a shortage could affect the U.S. market. The agency said in October that there had been no impact. That might be because the outbreak caused a pig-killing frenzy that initially yielded plenty of heparin. However, as the number of hogs slaughtered in China falls, so too will the volume of the raw material. Drugmakers including Germany’s Fresenius SE and South Africa’s Aspen Pharmacare Holdings Ltd. have mentioned shortages linked to rising prices. Fresenius’s Kabi unit told its U.S. customers in July that it put heparin on a protective allocation list due to a potential shortage. Massachusetts General Hospital warned in August of an impending global shortage; the chief of its emergency preparedness team said stock levels were so low at one point that the Boston center was two weeks away from having to cancel lifesaving cardiac surgery.

5. Are there other sources of heparin?

Yes. Heparin can be extracted from other farm animals and was historically prepared from cow lung and sheep intestines. The outbreak of mad cow disease in Europe in the 1990s made pigs a preferred source in many countries. The FDA has encouraged the development of bovine-sourced heparin as an alternate to pigs, though products from other sources may require rigorous testing to obtain regulatory approval, which could result in delays in their availability. Alternative blood-thinners aren’t typically as safe, effective or cheap.

6. Has this happened before?

Yes, though the current African swine fever outbreak is on a much bigger scale, heightening quality and supply concerns. The most recent shortages reported by the FDA involved Baxter International Inc. and Hospira Inc., now part of Pfizer Inc., and date to 2017, when Hurricane Maria disrupted manufacturing in Puerto Rico. In Australia, Pfizer advised authorities in November of a temporary shortage of two lines of heparin owing to manufacturing issues unrelated to the swine fever in China. A 2006-2007 outbreak in China of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, or blue-ear disease, slashed heparin supplies and allegedly prompted some adulteration of the raw material in China. U.S. and European regulatory officials determined a cheaper substance derived from shark cartilage was added to mimic heparin’s anticoagulant properties. That tainted product made its way into the global supply chain, killing 149 people in 11 countries, including at least 81 in the U.S. Baxter recalled its heparin injection products in the U.S. in 2008 but faced more than 1,000 related lawsuits. China never formally accepted responsibility. In October 2018, the Italian Medicines Agency found serious manufacturing violations during an inspection of a heparin plant in Sichuan, China, and recommended the facility be banned from supplying the drug ingredient to the European Union.

The Reference Shelf

- A 2012 issue brief from Pew Charitable Trusts reveals why heparin provides a “wake-up call on risks to the U.S. drug supply.”

- Bloomberg Law saw U.S. lawmakers still worried in 2018.

- A U.S. National Library of Medicine summary of heparin and its uses.

- A QuickTake explainer on how African swine fever is ravaging Asia’s hog herds.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jason Gale in Melbourne at j.gale@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Michael Patterson at mpatterson10@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner, Jodi Schneider

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.