Climate Talks Put Focus on How Carbon Markets Work, or Don't

Climate Talks Will Put Focus on How Carbon Markets Work, or Don't

(Bloomberg) -- It’s an idea that’s been around for more than two decades: To slow climate change, make polluters pay for the damage they cause. More than 60 jurisdictions — nations, states and cities — have adopted what’s known as carbon pricing, an approach hailed by environmentalists, politicians and even many oil companies as an elegant, free-market alternative to direct regulation. The concept has broad support from Asia to the U.S. and setting up rules for a global market is a focus of the COP26 climate talks in Scotland. Yet the implementation of carbon pricing has drawn legal challenges as well as complaints from business interests that it kills jobs.

1. How does carbon pricing work?

There are two main approaches. In one, carbon prices are set by governments as a tax or fee on carbon dioxide emitted. In the other, governments establish a limit on the total volume of emissions allowed, create a market and let participants in that market — utilities that produce electricity, most commonly — determine the exact price of carbon. The government sets a limit on the total volume of emissions allowed; permits are either allocated or purchased by polluters. The credits can be bought and sold, a system known as cap and trade.

2. Is it effective at changing behavior?

Levies from Europe’s carbon trading system have hastened the transition to cleaner natural gas. The U.K.’s carbon tax is credited with helping the country rapidly phase out coal. But environmentalists say most policy makers have traditionally been unwilling to set prices high enough to force changes in behavior.

3. How high does the price need to be?

A price range of $40-$80 a metric ton is needed to achieve the 2015 Paris Agreement’s main goal of limiting warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels, according to a 2021 World Bank report. Only about 4% of emissions are covered by a carbon price above $40 a ton. Keeping warming below the more ambitious Paris goal of a 1.5-degree Celsius limit would require introducing a price of $160 per ton or more by the end of the decade, according to consultant Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

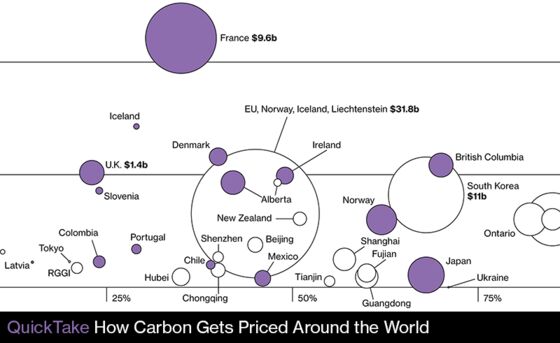

4. How widespread is carbon pricing?

The European Union and a dozen U.S. states operate carbon markets. Almost half of the biggest 500 companies in the world already have an internal carbon price they use to test the viability of new projects, according to the World Bank. Almost 30 nations have carbon taxes, which range from less than $1 a ton in Mexico to about $140 in Sweden. Many countries use permit trading alongside targeted taxes on dirty fuels such as coal. Still, carbon pricing covers only about 20% of global emissions.

5. What are some recent developments?

China rolled out a carbon market for its power sector in July 2021. Also that month, EU officials spelled out the biggest overhaul to date of its 16-year-old emissions market: Permits will be harder to come by, the program will be extended to include maritime transport, and airlines will eventually have to pay for all their pollution in the cap-and-trade program, as their free allowances will be phased out. The Supreme Court of Canada in March 2021 ruled that the nation’s carbon tax is constitutional, effectively settling years of political debate about its legality. In the U.S., where President Joe Biden vowed to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030, regional carbon markets will play a part, but the absence of a policy for a national price on emissions could slow progress. The American Petroleum Institute in March voted in favor of a tax or a national cap-and-trade program, with the understanding that it would replace existing regulations on greenhouse gases.

6. What opposition has there been?

Some political leaders have struggled to sell the system, since it raises the cost of goods and services, especially steel and cement. Australia repealed its carbon tax in 2014 after it was blamed for destroying jobs. In the U.S., even as energy companies have embraced the idea, conservative politicians, including most of the Republican Party, have opposed carbon taxes and cap-and-trade systems. Some business leaders say it distorts markets for goods that come from countries that don’t levy a price on pollution; to address that, the EU is implementing a so-called Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism on goods from jurisdictions with laxer pollution rules, and the idea is being considered in the U.S. as well.

The Reference Shelf

- A Bloomberg story on negotiations over carbon pricing.

- The World Bank’s 2021 report on trends in carbon pricing.

- QuickTakes on China’s carbon market and Europe’s carbon border tax.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.