Contingent Convertibles

Contingent Convertibles

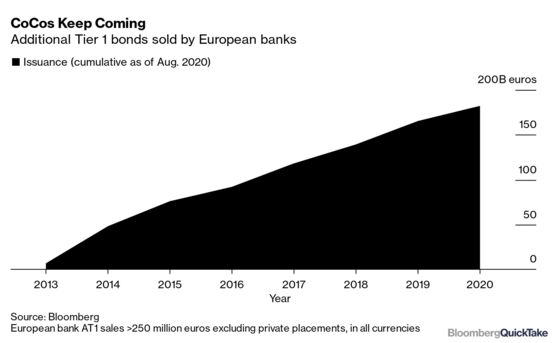

(Bloomberg) -- It’s a high-yield investment with a hand grenade attached. An asset carried gingerly with the hope that it won’t explode, leaving investors in a hole. Welcome to a class of securities tailor-made for banks that’s become popular in Europe: contingent convertibles, also known as CoCo bonds. A cross between a bond and a stock, CoCos are helping banks bolster capital to meet regulations designed to prevent a repeat of the taxpayer bailouts of the 2008 financial crisis. Some investors are skeptical that the extra yield CoCos offer really reflects their dangers, but about 200 issues worth more than a combined 180 billion euros ($212 billion) have been snapped up since they first came to market in 2013. While CoCos are supposed to make financial markets safer, critics question whether regulators have unwittingly created new risks.

The Situation

CoCos were tested again as the coronavirus roiled markets, pushing yields to a record of almost 15% in March 2020 as fears grew that interest payments could be skipped. They largely recovered in the months that followed, thanks to regulatory restrictions on dividends to preserve cash and relief measures that are helping boost banks’ capital buffers. New sales halted for nearly three months before resuming in May. It was the market’s biggest challenge since 2017, when Banco Popular Espanol SA, Spain’s sixth-biggest bank, was swallowed by rival Banco Santander SA to prevent its collapse. The takeover wiped out 1.25 billion euros worth of Popular’s CoCos. The CoCos sold since 2013 are used to raise Additional Tier 1 (AT1) capital, a lender’s first line of defense after equity against financial shocks. While hedge funds seeking higher yields are keen buyers, the bonds are also purchased by asset managers hungry for income in a low interest rate environment. In mid-2020, major currency CoCos sold during the year paid a coupon of between 3.375% and 7.5%, roughly double or even triple that of more secure senior bank bonds.

The Background

Regulators cleared the way for the sale of CoCos because they set the stage for bondholders — rather than taxpayers — to feel the pain of bank rescues and gave lenders a way to raise funds without further diluting shareholders. They are “perpetual,” meaning they may never be redeemed, though the hope among buyers has been that banks would repurchase them at the first opportunity. Santander became the first lender to skip a voluntary call option in 2019 and others including Deutsche Bank AG have since done the same, a win for the instruments’ inventors. CoCo interest payments can be switched off if capital ratios fall to dangerously low levels (that’s the contingent part). If a bank’s financial health deteriorates further, CoCos can be written down to zero or converted into equity (that’s the convertible part). The need for such an instrument has been met differently in various regions: While Europe opted for CoCos to boost Tier 1 capital, U.S. banks employ a form of preferred stock and China’s lenders are using a cross between the two. While CoCos are technically bonds (and thus interest payments can be made from pretax earnings), they display many properties of an equity.

The Argument

Many banks are selling more CoCos than initially planned, after regulators eased a rule at the height of the March 2020 crisis. That allowed them to meet some of the Pillar 2 capital requirement (going beyond minimum requirements) with debt rather than equity. CoCo bonds were developed partly because regulators noted that investors often did a better job of predicting which banks would buckle than officials had themselves. CoCos are meant to harness this “wisdom of the crowd” by putting bondholders on the front line, giving them an interest in the health of banks. The broader concern has been that problems with a specific bank or a hiccup in the financial system could cause investors to wake up to the inherent risk and flee all CoCos, destabilizing the corporate bond market. Critics charge that the securities are too complex to be properly understood, too varied and too much like equity to be considered bonds. The biggest test for the CoCo market will come when a large, global bank imposes losses on bondholders. Until then, critics say, we won’t know whether CoCos helped save the banking system — or helped sink it.

Thomas Beardsworth and John Glover contributed to an earlier version of this story.

The Reference Shelf

- A QuickTake Q&A on how bondholders were wiped out in the rescue of Banco Popular.

- A primer on CoCos from the Bank for International Settlements.

- Andrew Haldane from the Bank of England and Piergiorgio Alessandri of the Bank of Italy set out the theoretical case for CoCos in a 2009 paper. Haldane, the BOE’s chief economist, described them in a speech in 2011.

- QuickTakes on Capital Requirements and Too Big to Fail.

- The EU’s Capital Requirements Directive.

- The Basel committee’s FAQ on bank capital.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.