Clubs, Covenants, Mezzanines, a Guide to Private Debt

Clubs, Covenants, Mezzanines, a Guide to Private Debt

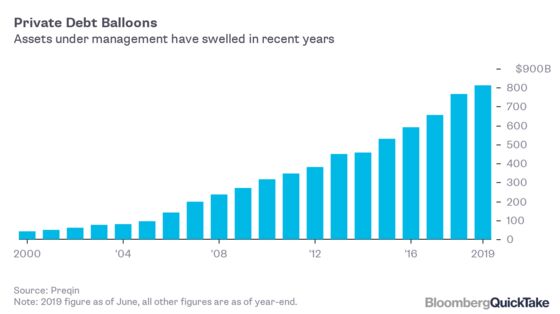

(Bloomberg) -- Finance has seen many sea changes in the last decade, but in lending none larger than the explosive growth of what’s known variously as private debt, private credit, alternative lending or shadow banking. As traditional lenders stepped back from providing capital and central banks worked to keep the market music going, private firms have pooled money to issue ever-increasing amounts of debt, driving the sector’s total global assets to $812 billion in 2019. That rise has been welcomed by yield-hungry investors, eager to cash in on the asset class’s juicy returns, private equity firms looking to finance buyouts and borrowers who would struggle to drum up capital elsewhere. It’s also fueling anxiety among regulators worried that investors in the field, from mom-and-pop to big private equity firms, are taking on too much risk in their search for high yields. Here’s a guide to the main flavors.

Business Development Companies (BDCs)

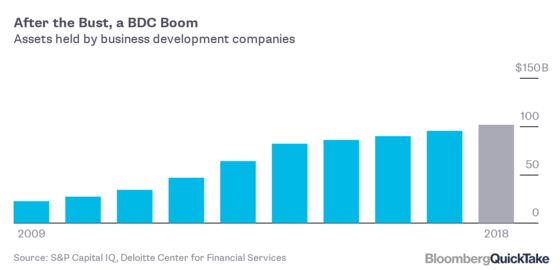

The roots of business development companies, a type of closed-end investment firm, date back to a 1980 law meant to boost Main Street businesses deemed too small or risky for Wall Street banks. The law offered investors significant tax advantages that fueled comfortable dividends. Retail investors still make up a large swath of the equity holders for these types of private credit vehicles. But some of the players are anything but small. Ares Capital Corp., a behemoth BDC with $14 billion in assets, in late 2018 participated in a $792 million loan for the refinancing of Pathway Vet Alliance, a private equity-backed operator of veterinary hospitals. Total assets in BDCs jumped to $101 billion in 2018 from $23 billion in total assets in 2009, according to Deloitte LLP.

Lending Clubs

When a middle market borrower -- typically bringing in $100 million or less in Ebitda -- wants to arrange financing it often turns to a “club” of lenders -- a small group that tends to work together repeatedly. A club loan is typically smaller than those seen in the broader leveraged loan market -- an average of $137 million in most of 2019, compared to $194 million for syndicated deals to similar borrowers, according to research firm Covenant Review. Club participants can include banks that cater to smaller businesses as well as direct lenders. Borrowers and sponsors often prefer working with a club rather than selling a loan to a large number of investors because it’s faster and easier.

Covenants

Preparing for things that can go wrong is an everyday part of the job for credit investors. Covenants are an important tool for limiting their risk. They’re items written into bond agreements that can, for instance, require borrowers to meet certain financial measures. In extreme cases, they can even give lenders the right to seize the business. But in the recent rush to lend, covenant protections have been eroding across both private and public markets. The bulk of deals in the broadly syndicated leveraged loan market in Europe and the U.S. are what’s called covenant-lite -- the market euphemism for having few protections -- according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Within private credit, covenants are more common, but many investors worry that they’ve become riddled with loopholes, are tied to inflated earnings figures or are written in ways that they can’t be triggered.

Direct Lending

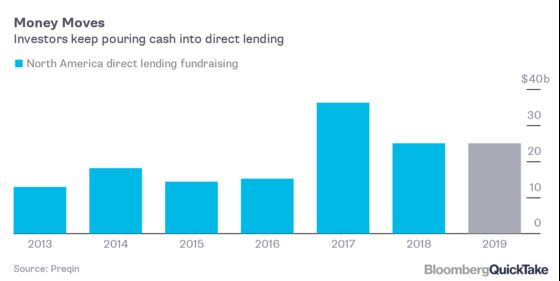

Direct lending is essentially traditional bank lending, just provided by non-banks. The firms that do the lending pool money from investors like insurers, pension funds and family offices, all itching to make more money in a low-interest rate environment. Direct lenders, also known as shadow banks, charge a premium to provide the debt to borrowers that likely wouldn’t be able to get financing elsewhere. That can make it a win-win, so long as nothing goes wrong. Market watchers have said that intense competition has eroded quality, making loans riskier in the asset class, which is largely untested in a downturn. Fundraising for direct lending in Europe reached a fresh record in 2019, while in North America, the largest hub for the strategy, cash poured into the asset class hit $25.1 billion last year, down from $26.4 billion in 2018, according to Preqin.

Mezzanine

In buildings, mezzanines are below everything else except for the ground floor, and in bankruptcies or distressed situations, mezzanine lenders get paid after all other lenders get the collateral they were promised but before anything goes out to equity shareholders. In return for the increased risk, mezzanine loans, which are typically unrated, promise bigger payoffs: Preqin data shows mezzanine private credit funds returned just over 10% annually over a five-year period ending March 2019. By comparison, direct lending funds’ five-year annualized return was just under 7%. Mezzanine returns generally come via a bespoke mix of cash interest, payment-in-kind and equity warrants. That makes it the most equity-like of debt instruments. Losses on mezzanine debt during the financial crisis dinged its appeal -- and more recently, despite the high returns, the strategy has faced competition from other products like unitranche financing.

Middle Market

There is no universally accepted revenue range that defines the middle market companies that are the focus of private credit. Most observers use a range of $5 million to $50 million in revenue, while a small slice stretch the definition to an upper limit of $100 million to $1 billion. However you define it, there seems to be a consensus that the so-called middle-market lending is overcrowded, and more competition has started eroding the yields that made direct lending appealing in the first place. There is also concern that the huge shift of assets from public to private markets could hurt investors who may feel the pressure to offload assets during a downturn -- and may have trouble selling the illiquid debt.

Recurring Revenue Loans

It may seem shocking that asset managers like Ares Management and Vista Equity Partners Management make loans to borrowers that don’t have any earnings, but it’s a business that’s a growing part of the debt landscape. This type of debt, known as recurring revenue loans, is in some senses a credit-market parallel to venture-capital equity investments in startups. The payoff is based on expected revenue from ongoing contracts the borrower has. Financial targets, like when the borrowers must turn a profit, are typically woven into these agreements. These structures, which are a subset of a broader category of venture lending, provide young companies with capital to grow their business or market early-stage products without diluting equity, which is attractive to some owners.

Senior Stretch

Much like the name implies, this type of loan combines senior debt entitled to first call on collateral with debt that’s lower in the payment hierarchy, and so “stretches” past the typical senior debt. The lender gets compensated handsomely for the extra risk. Strict parameters for what comprises a senior stretch loan are hard to come by, but depending on geography, lenders often consider anything with roughly between 4.5 times to 6 times debt-to-Ebitda as falling into this category. Private credit firms struggling to invest in high-quality companies may also dub transactions “senior stretch” to help allay investors’ concerns that they’re investing in lower quality deals.

Unitranche

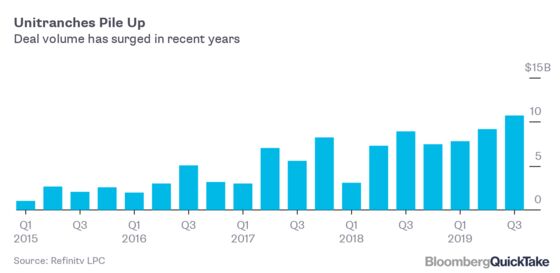

Private equity firms are increasingly turning to an obscure type of loan called a unitranche to fund larger and larger buyouts. Like a senior stretch, unitranches blend first-priority and subordinated loans into a single facility, but one that’s usually shared among a handful of lenders. They’ve been surging as borrowers bypass conventional sources of financing. Previously used solely to fund middle-market transactions, volume in the U.S. reached a record $10.7 billion in the third quarter of 2019 as non-traditional lenders deployed more cash for deals that in the past may have gone to the institutional loan market. Sponsors and borrowers find them appealing since they can be put together faster than other syndicated debt, and interest rates on the structures are getting lower. Some worry that the structure, which is sometimes carved up between the lenders via sophisticated side deals, remains unproven, especially in the face of a potential economic downturn and the stress on repayments that can bring.

Venture Debt

Venture debt is usually used by early-stage companies and startups as either an alternative or a complementary method to equity venture financing. This financing is considered founder-friendly, as it prevents further dilution of the equity stake of a company’s existing investors. Some startups opt for venture debt for their long-term financing to retain control of the business longer, which could potentially create greater economic value for its co-founders, employees and other early supporters, and also to avoid having new board members. Typically, these loans are secured by a company’s assets, including intellectual property and equipment and the repayment happens in monthly payments. As lending to early-stage companies can be a risky business, venture debt lenders take warrants in either common or preferred stock to help mitigate risks and lock in an upside if the borrower succeeds.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTake explainers on direct lending, business development companies, shadow banking and leveraged loans.

- A look at the performance of private credit funds from the Institute for Private Capital.

- A report on the future of private credit from trade group the Alternative Credit Council.

- Bloomberg features on unitranches, recurring revenue loans and BDCs.

To contact the reporters on this story: Kelsey Butler in New York at kbutler55@bloomberg.net;Rachel McGovern in Dublin at rmcgovern17@bloomberg.net;Paula Sambo in Toronto at psambo@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: John O'Neil at joneil18@bloomberg.net, Adam Cataldo

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.