Choking China

Choking China

(Bloomberg) -- For many people in China, the most visible problem isn’t the country’s slowing economy, corruption or social harmony. It’s dirty air. Pollution is shortening lives in the world’s most populous nation and, by some accounts, has been the main cause of social unrest in recent years. After Beijing’s “airpocalypse” in 2014, President Xi Jinping pledged to protect the environment with an “iron hand.” As economic growth slowed however, the government loosened some curbs to keep factories running, and winter skies got grayer. It’s a reminder of the trade-offs at the heart of China’s transition from developing country into prosperous, modern nation, forcing the Communist Party to balance the rush for growth against the threats to life and health. Can China clear the air?

The Situation

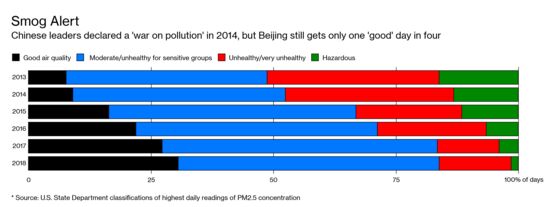

Progress has been erratic. In 2013, levels of PM2.5, airborne particles that pose the greatest threat to human health, peaked in Beijing at 35 times the World Health Organization’s recommended limit. The capital’s 21 million residents donned face masks, kept their kids indoors and complained vociferously on social networks. Premier Li Keqiang declared a “war on pollution,” while warning it would take time. In 2015 Beijing issued its first red alert — the highest of four levels — as an ash cloud bigger than Spain settled over northern China. More alerts followed but air quality has generally improved as authorities tightened environmental regulations, scrapped some coal-fired power plants and switched millions of homes and businesses from coal to cleaner-burning natural gas. There have been setbacks. In the four months ending Jan. 31, 2019, average PM2.5 concentrations in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region — home to more than 100 million people — jumped 6.7 percent from a year earlier. The capital was under an orange smog alert in early March as delegates arrived for the National People’s Congress. Health studies have raised alarm bells. One report said pollution may be cutting lives in northern China short by five years; the WHO estimates more than 1 million Chinese died from dirty air in 2016; another study put the tally at 4,000 deaths a day. Other research links pollution and lung cancer.

The Background

Air pollution has been killing people since the Industrial Revolution, and China’s today is no worse than London’s pea soup in the 19th century or Japan’s smoggy 1960s. Yet more is known about the dangers now, and global warming raises the stakes: China overtook the U.S. as the biggest source of greenhouse gases in 2006, helping to put the globe on a path to miss United Nations targets for stemming the rise in the Earth’s temperature. Coal still provides almost 60 percent of China’s energy, meaning it will take years to change that dependence. China’s leaders have pledged to be less secretive and not to repeat mistakes that cost them public trust during the SARS outbreak in 2003 and a tainted milk scandal in 2008. China’s contaminated water and soil are also prompting public worry, along with food and drug safety. China’s air pollution blows into Japan and South Korea and contributes to smog as far away as California.

The Argument

While the scale of the problem is massive, so has China’s top-down response been. It signed a historic agreement with the U.S. in 2014 to limit greenhouse gasses and promised that its carbon emissions will peak around 2030. China is the world’s biggest clean-energy investor and is building its own carbon-trading market like in Europe. It created a stronger watchdog, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment. Yet the war promises to be a long one. The ministry must battle other powerful bureaucracies as well as local officials and other vested interests to ensure its directives are followed. Residents in less-populated parts of the country complain about power plants – and smog – being shifted to them. The two most-polluted cities in China in 2018 were in the western Xinjiang region, where ethnic Uighurs, a minority group, predominate. China is expected to add around 20 percent more coal-fired power capacity from 2018 to 2025, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, bringing the total to more than 1,200 gigawatts – almost five times more than the U.S. has now.

The Reference Shelf

- How China’s war on pollution could change the world.

- “Under the Dome,” a documentary film by former China Central Television reporter Chai Jing.

- Website providing unofficial aggregation of China’s air quality data.

- Greenpeace campaign for reducing air pollution in China and the World Health Organization’s topic page on air pollution.

- A live graphic showing how much carbon dioxide the world is churning out.

- The World Bank and Development Research Center’s report on China 2030.

Natasha Khan contributed to an earlier version of this article.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Grant Clark at gclark@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg