China’s Overseas IPOs

China’s Overseas IPOs

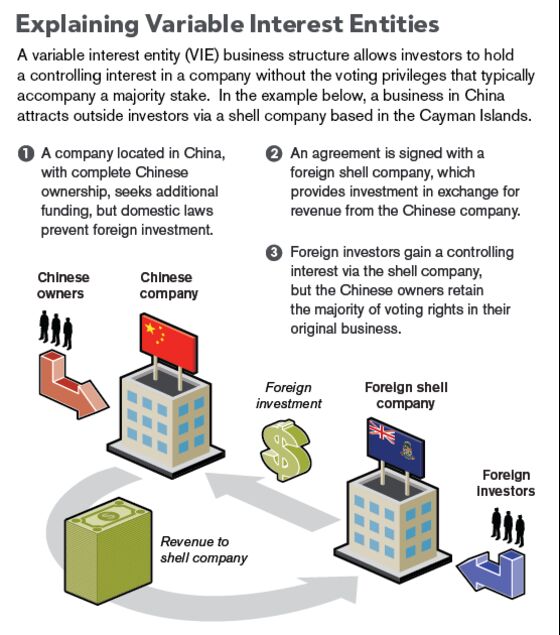

(Bloomberg) -- The world’s biggest population is more active online than ever, and foreign investors naturally want a piece of the action. A little problem: Chinese law restricts foreign investment in internet companies (along with telecommunications, mining and private education). Not to worry — where there’s a will, there’s a way, in this case an exotic corporate structure that magically turns a Chinese company into a foreign one with shares that overseas investors can buy. And they have. Chinese firms have raised more than $80 billion through first-time share sales in the U.S. over the past decade, including $4.4 billion in June 2021 by ride-hailing giant Didi Global Inc. It’s a risky business, though: while several Chinese agencies have begun to acknowledge the existence of VIEs for the first time in legal documents, nobody knows whether the Chinese government considers these structures legal. They may soon find out, however, as China amps up scrutiny of overseas listings by any Chinese company that operates mainly onshore.

The Situation

China’s gargantuan online retailer Alibaba sold shares to U.S. investors in 2014, raising $25 billion in the largest initial public offering in history. To do this, it used a standard legal shuffle to deploy a variable interest entity, meaning it transfers profits to an offshore corporation with shares that foreign investors can own. Pioneered by the Chinese-language media company Sina in its IPO in 2000, the VIE structure is used by many of China’s internet companies, including Didi. Investors don’t own shares in Alibaba’s profitable e-commerce business. Instead, they hold a piece of a shell company in the Cayman Islands. The earlier Chinese companies went public with as much as 99% of their revenue tied to the VIE, but only 12% of Alibaba’s revenue and 8% of its assets were fixed to the structure. Shareholders are betting on rapid growth in China’s internet use: 70% of the population was online in 2020 — 989 million internet users. A lot is at stake for both China's national champions and U.S. investors including teachers and firefighters whose public pension funds have poured billions into China's tech firms. Among them: the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the Washington State Investment Board and the Teacher Retirement System of Texas.

The Background

The Chinese government divides its major industries into categories. Some are encouraged or permitted to offer ownership interests to foreigners. Others face restrictions or prohibition. Many foreign industry leaders say these rules violate the market reform agreements the Chinese government signed when it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. Executives in industries like steel and mining have long called for China to be more open to foreign direct investment. In 2012, China’s Supreme Court broke up one form of a VIE when it invalidated contracts made between Minsheng Bank of Hong Kong and its mainland proxy, cutting off foreign investors from future profits. Chinese internet companies say that ruling doesn’t apply to them because the bank didn’t use the typical VIE structure, leaving itself exposed to lawsuits.

The Argument

Chinese companies have insisted they’ve minimized the risks associated with the VIE structure, although no Chinese regulatory body has officially approved one. For years China largely ignored them. But in introducing new anti-monopoly rules in February 2021 — part of a broader effort to curb the power of increasingly pervasive Big Tech companies — the Chinese government made reference to the need for official approval for deals involving VIEs. A week after Didi’s IPO, the State Council, China’s cabinet, said rules for overseas listings would be revised and regulators would step up oversight of companies trading in offshore markets, which sent shares in Didi and other Chinese tech companies plummeting. At the end of the year China unveiled sweeping regulations governing overseas share sales that stopped short of a ban on IPOs by companies using VIEs, but will make the process more difficult and costly. All this is playing out as U.S. exchanges become more hostile to Chinese companies, which may face delisting if they refuse to hand over financial information to American regulators, and Beijing encourages them to list back home. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in July paused approvals for new Chinese IPOs, in part over a lack of disclosure around VIEs.

The Reference Shelf

- The law firm O’Melveny & Myers published a 2011 report, “VIE Structures in China: What You Need to Know.”

- PricewaterhouseCoopers offered 245 pages of guidance in 2013 on accounting for VIE structures.

- An explainer on VIEs by the Hong Kong research firm Forensic Asia explores why China doesn’t let its companies list shares overseas.

- More QuickTakes on Alibaba, on Didi and China’s broad crackdown on the tech sector, and U.S.-China flashpoints.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.