Brazil’s Disappointment

Brazil’s Highs and Lows

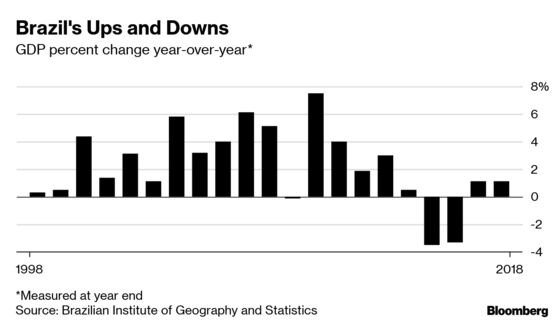

(Bloomberg) -- In the course of a decade, Brazil has gone from rising power to fallen star. Latin America’s largest economy enjoyed effervescent years under President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, whose eight-year tenure through 2010 coincided with a global commodities boom. Now Lula is in jail, his successor has been impeached and her replacement has been charged in an ongoing corruption investigation. Street crime is epidemic in Brazil’s cities, and the country has endured its deepest-ever recession. Fed up, Brazilians in 2018 elected a chauvinistic former Army captain, Jair Bolsonaro, to reverse the decline. Ending the 13-year rule of the leftist Workers’ Party, he promised to remake Brazil with an aggressive approach to crime and pro-market economic policies. Critics fear he’ll undermine democratic norms, stifle dissent and deepen Brazil’s divisions.

The Situation

Prospects for a quick economic revival faded in the months after Bolsonaro took office in January as his administration struggled to negotiate legislation with Congress. Gross domestic product shrank in the first quarter of 2019, its first contraction since the 2016 end of the recession, and unemployment remained stubbornly high at 13%. Bolsonaro’s University of Chicago-trained economy minister, Paulo Guedes, set out to privatize some of Brazil’s long-protected stable of 400 state-owned companies, more than any other developed country. Within five months, a new infrastructure ministry had auctioned 23 of them, including airports, port terminals and a railway, raising 8 billion reais ($2 billion). At the same time, bitter political and cultural disagreements among government officials, lawmakers and Bolsonaro’s own sons were fought in the open on social media, dominating the headlines. Hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets in May to demonstrate against plans to freeze funding for universities. The rancor threatened to derail Bolsonaro’s highest-priority plan: an overhaul of the insolvent state pension system and increase in the retirement age. That’s essential to ensuring sustainability of the country’s debt and putting it on course to regain the investment-grade rating it lost in 2015. On crime, Bolsonaro has vowed to meet violence with violence. He issued a decree easing restrictions on gun possession, framing it as an anti-crime measure.

The Background

Brazil has suffered boom-and-bust cycles and political instability since independence from Portugal in 1822. Almost half its 2018 exports were raw products, so its prosperity is sensitive to the vagaries of the commodities markets. Brazil’s natural wealth should make it a powerhouse: It’s the fifth-largest country in the world by land mass and population, with 210 million people. Its offshore oil reserves include the Western Hemisphere’s biggest discovery since 1976. It has the second-largest iron ore reserves and is among the top producers of soybeans and corn. On the other hand, its distribution of wealth remains among the world’s most unequal. Good times provided cash to beef up the Bolsa Familia or “family grant” social-welfare program begun by Lula, which became an international model for eradicating poverty. The new middle class went shopping, boosting economic growth. But that progress stopped when commodity prices fell and industry sputtered. Brazilians’ confidence in their leaders, meantime, was eroded by the sprawling criminal investigation known as Operation Carwash, which revealed a kickbacks scandal involving state-run companies and builders that were among the nation’s biggest political donors.

The Argument

Bolsonaro connected with voters turned off by what they saw as a system rigged by an entitled, corrupt political class. His embrace of gun ownership, incendiary comments about homosexuality and appointment of a corruption-fighting judge as justice minister resonated with many conservative Brazilians, including Catholics, who have grown alarmed at what they see as their nation’s moral decline. At the same time, his reluctance to engage with political parties he long criticized as corrupt meant he lacked the alliances needed to push his agenda forward once he gained power. His government was beset by a deep division between a relatively pragmatic wing made up of former military officials and a group of radicals demanding a more ideological administration. Critics worry that his nostalgia for the military dictatorship that ruled from 1964 to 1985, a history of offensive statements about women and minorities and an apparent disregard for government checks and balances show a lack of commitment to democracy and a tolerant society. A poll by research group Datafolha found Bolsonaro had a lower approval rating after 100 days than any other leader since the country’s return to democracy.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTake explainers on Brazil’s pension system and how Brazil’s economic recovery got run off the road.

- Bolsonaro’s election raised fears about deforestation of the Amazon.

- Economists are puzzling over why a recovery is eluding Brazil for a third year.

- A profile of economy “super minister” Paulo Guedes.

- Foreign Affairs on “the rise of evangelical conservatism” in Brazil.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Walter Brandimarte at wbrandimarte@bloomberg.net, Laurence Arnold

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.