Boeing’s Grounded 737 Max: The Story So Far

Boeing's Grounded 737 Max: The Story So Far

(Bloomberg) -- Two crashes within five months -- Lion Air Flight 610 in October off the coast of Indonesia and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 in March outside Addis Ababa -- killed 346 people and led to a global grounding of Boeing Co.’s relatively new 737 Max jets. Numerous investigations are under way, including ones looking at how U.S. flight regulators came to certify the airplane. Boeing has abandoned its financial forecast for 2019 as it faces questions about the plane’s development and testing and its own transparency. The Max is the fourth generation of a venerable brand -- Boeing’s best-selling 737 series, first flown in 1967.

1. How disruptive have the groundings been?

With many more Max jets in production than in service, not very. In the U.S., for example, the Max makes up about 3 percent of the mainline fleet. Southwest Airlines, the biggest U.S. operator, said the grounding was causing about 130 daily cancellations. Airlines have used other planes in their fleet or leased aircraft. Travelers have suffered little disruption, though there’s a risk ticket prices may rise, at least during peak season in some markets.

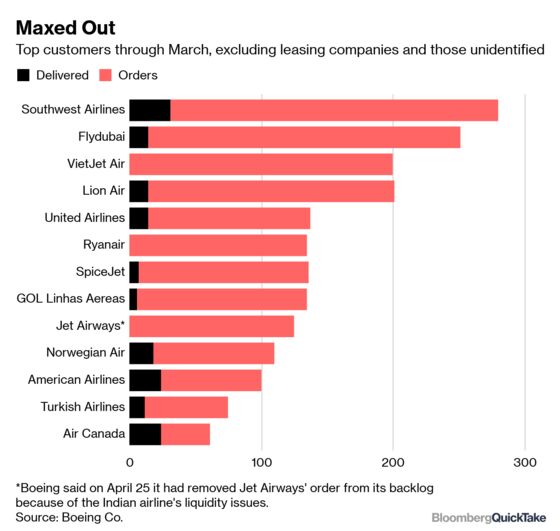

2. Which airlines were using the 737 Max?

The main operators include Southwest (31 in the fleet through February), American Airlines (24) and Air Canada (24). Chinese airlines account for about 20 percent of 737 Max deliveries globally. (Click here for the full list.) As of March 31, Chicago-based Boeing reported 387 deliveries of the single-aisle Max jets to 48 airlines or leasing companies, with orders from around 80 operators for about 4,400 more. Most sales are the Max 8, the model involved in both crashes. (There’s also, from smallest to biggest, a Max 7, 9 and 10.)

3. What caused the crashes?

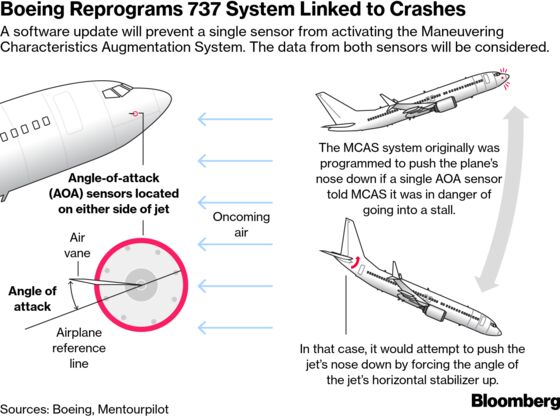

In both crashes, pilots were overwhelmed by an obscure new flight control feature added to the Max known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS. The system kicked on due to an erroneous sensor reading and started nudging the plane nose downward. Pilots commanding the doomed Ethiopian Air jet were hit with a cascade of malfunctions and alarms seconds after taking off from the Ethiopian capital, according to a preliminary report.

4. What is MCAS?

It’s software that Boeing installed in the 737 Max to help the plane behave similarly to previous models under certain circumstances. The system activates when the plane appears to be at risk of stalling, a situation in which the wings are losing lift because the jet is climbing too steeply. (The use of new, bigger engines on the 737 Max required Boeing’s designers to mount the turbines farther forward on the wings to give them proper ground clearance. That changed the plane’s center of gravity.) The software had a critical flaw: It relies on the reading from a single sensor called the angle of attack vane, which measures the nose of the plane against onrushing wind. Boeing said there was a simple procedure for shutting off MCAS in case of malfunction. The day before the Lion Air crash, an off-duty pilot on the same aircraft recognized the problem and told the crew how to disable the system, saving the plane.

5. Who approved this system?

The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration gave final certification to the 737 Max in March 2017 and it entered commercial service two months later. Under its Organization Designation Authorization program, established in 2005, the FAA delegated to Boeing the authority to perform some safety-certification work on its behalf. FAA employees warned as far back as seven years ago that Boeing had too much sway over safety approvals of new aircraft. Boeing said in May that it had known months before the Indonesia crash that the cockpit alert wasn’t working the way it had told buyers, but it did not share those findings with airlines or the FAA until after the Lion Air jet went down.

6. What can be done now?

Boeing has redesigned software linked to the two crashes to prevent it from erroneously misfiring and overwhelming pilots. The changes face a review by the FAA and other regulators. The certification of the plane’s flight control system will also be reviewed by a technical panel convened by the FAA, with members from eight countries and the European Union. Meanwhile, U.S. prosecutors and congressional investigators are exploring how the flaws in the system escaped notice. The FAA and Boeing said they also will require enhanced pilot training and additional references to the MCAS system in flight manuals. There’s no time frame set.

7. What does this mean for Boeing?

The company has suspended deliveries of the 737 Max and is cutting monthly output to 42 from 52, while maintaining it still has “full confidence” in the plane. Lion Air and several other carriers have said they are reconsidering their orders. Norwegian Air said it will seek compensation for the grounding of about 1 percent of its seats. There’s also the prospect of substantial payouts to the families of passengers if Boeing is found responsible for the crashes. In the week after the second crash, Boeing lost more than $22 billion, or 12 percent, of its market value. In April, the company missed its quarterly earnings estimates for just the second time in five years. The entire 737 range accounts for almost one-third of Boeing’s operating profit.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on MCAS and lawsuits in the U.S. from the Lion Air crash.

- Off-duty pilot saved doomed 737 Max on next-to-last flight.

- Empty coffins buried: BBC.

- Boeing’s reputation on the line.

- This graphic identifies 737 Max customers.

- A New York Times in-depth examination of the Lion Air crash.

- Flawed analysis, failed oversight: The Seattle Times.

- Boeing’s 737 Max page.

- China gets tough on the 737 Max.

--With assistance from Alan Levin and Julie Johnsson.

To contact the reporter on this story: Kyunghee Park in Singapore at kpark3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jon Morgan at jmorgan97@bloomberg.net, Grant Clark, Paul Geitner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.