Behind the NYSE’s Swerves on Delisting China Stocks: QuickTake

Behind the NYSE’s Swerves on Delisting China Stocks

(Bloomberg) -- In the course of a week, the New York Stock Exchange said it would delist a trio of Chinese companies, then that it wouldn’t and then that it would, stoking confusion among investors globally. The moves were the result of an initiative by then-President Donald Trump to punish companies with close ties to the Chinese military as part of a crescendo in U.S.-China tensions. The dizzying sequence reflects ambiguity over both how Trump’s push would work and what its impact would be. As global index providers, banks and money managers raced to comply with the order, investors were bracing for the possibility of wider fallout. The three firms targeted, meanwhile, have asked the NYSE for a review.

1. What does delisting mean?

It’s the process of removing a stock from a public exchange where it’s been traded. The most common reason for a delisting is when a company runs into financial trouble and its value falls below a minimum set by an exchange for inclusion or it is purchased by a different entity. Companies can also be delisted to comply with U.S. laws like Trump’s executive order.

2. What’s led to the move to delist these stocks?

In November, Trump issued an executive order requiring investors to pull out of Chinese companies that were deemed a threat to U.S. national security. The companies must have been categorized by the Treasury Department or the Pentagon as being tied to the Communist Chinese military. The order said that designated stocks could not be purchased by Americans starting on Jan. 11, and that holdings by Americans must be fully divested by Nov. 11, when transactions will be frozen.

3. What happened with the NYSE?

On New Year’s Eve, it announced it would delist shares of China Mobile Ltd., China Telecom Corp., and China Unicom Hong Kong Ltd. to comply with Trump’s executive order after the Treasury designated them as Chinese “military companies.” Four days later, the exchange went back on the decision, saying it would no longer delist the companies after consultation with regulatory authorities. That change of tone didn’t last long, as flack from the White House pressured the exchange to make a second U-turn roughly 24 hours later.

4. What did those turnarounds do?

The confusion that gripped Wall Street caused the trio of companies to lose roughly $8.7 billion in market value on Jan. 4 -- on top of the more than $30 billion shed in the final weeks of 2020 -- only to snap back higher then tumble as the roller coaster week marched on. (They subsequently rebounded in trading in Hong Kong, where they’re also listed.) Index providers including MSCI, FTSE Russell and S&P Dow Jones Indices moved to delete companies affected by Trump’s order. Lawyers said the drama exposed the ambiguities of the government’s instructions and added to a whirlwind of trading.

5. Could it be reversed again?

It’s possible. Hours after President Joe Biden was sworn in as Trump’s successor on Jan. 20, the companies announced individually that they had requested a review by the NYSE, and also asked for trading suspensions to be stayed while it’s undertaken. The review will be scheduled at least 25 business days from the date the request is filed, they said. Meanwhile, Biden has the power to reverse the bans, but hasn’t revealed his intentions yet, Analysts at Jefferies said Jan. 15 they expect some de-escalation in U.S.-China disputes over technology, and predict America under Biden may move to technology-specific export curbs rather than targeting companies.

6. What happens to the NYSE-listed shares once they’re delisted?

The impact is a little indirect, because shares of non-American companies aren’t traded directly on American exchanges, but through holdings known as American depository receipts, or ADRs. The ADRs can equal underlying shares on a one-for-one basis, a fraction, or multiple shares of the company. For the three telecom companies, their ADRs were Level III -- the most prestigious category -- used by large companies to establish or expand their presence in U.S. markets.

7. What will happen to the ADRs?

Starting Jan. 11, they’ll either be sold, converted to equity traded in Asia or moved to so-called pink sheets. That means that investors don’t have to sell their shares immediately. But a transfer to pink sheets -- a listing service for stocks that trade over-the-counter and not on NYSE or exchanges like the Nasdaq -- means there will be fewer investors to buy the stock before the November deadline.

8. What are pink sheet stocks?

Pink sheet stocks lack liquidity and can be volatile with large spreads between what a bidder is willing to pay and the price a seller is asking for. The securities have historically been seen as highly speculative and recently entered the mainstream through the movie, “The Wolf of Wall Street.” In addition, under the executive order, buying pink sheets of China Mobile or the other two telecoms would be illegal for Americans, so many investors could elect to bail on their positions before the order takes effect.

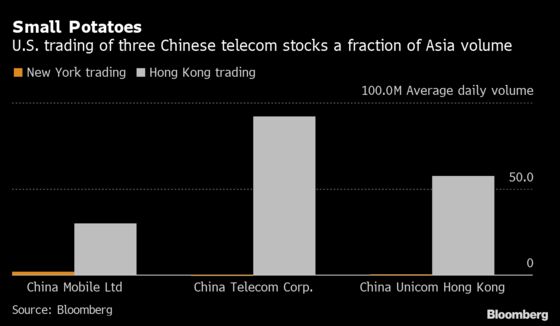

9. How big a deal is this?

That’s hotly debated. The removal of the ADRs and restrictions on American investing will limit the capital the three stocks can attract but some on Wall Street have argued that the removal was mainly a blow to investor sentiment. They point to the fact that U.S. trading for the trio makes up a tiny fraction of the volume seen in Asia for some companies. In a related move, major banks including Goldman Sachs Group Inc. have delisted hundreds of Hong Kong-listed investment products linked to those stocks, and the city’s most actively traded ETF, the Tracker Fund of Hong Kong, said it was no longer “appropriate” for U.S. investors.

10. Will more Chinese companies get delisted?

It’s possible as long as the executive order stands. Dozens of companies are on the Pentagon blacklist including smartphone giant Xiaomi Corp., which was added on Jan. 14. Unless that’s reversed, it risks being delisted from U.S. exchanges and deleted from global benchmark indexes. Trump also signed an order that bans U.S. transactions on eight Chinese apps including Tencent’s digital wallets.

11. Could China retaliate?

It’s already started to. China issued new rules Jan. 9 to shield its firms from having to comply with “unjustified” sanctions. The regulations also would allow them to sue in Chinese courts for any damages they suffer as a result of foreign companies that do comply with them, although it’s unclear how that might work. Separately, Bloomberg Intelligence’s Andrew Chan called out MGM China, Sands China and Wynn Macau as potential targets for the Chinese government as all three Macau casino companies have U.S. parent firms.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on how China stars like Alibaba could be forced from the U.S. and U.S.-China flashpoints to watch.

- A Q&A on the Pentagon and Commerce department blacklists.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Shuli Ren on NYSE’s change of heart.

- U.S. Department of the Treasury FAQs on the Chinese military companies sanctions.

- President Trump’s Nov. 17 executive order addressing the threats from investing in military companies.

- The 2020 annual report from the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.