Why Australia Faces Another Border Security Election

Australia Faces Another Border Security Election: QuickTake Q&A

(Bloomberg) -- The fate of around 1,020 people living in refugee camps on remote South Pacific islands is set to add fuel to Australia’s already heated federal election campaign. No sooner had legislators passed a new law on Feb. 13 that gives doctors more say over when asylum seekers should be sent to Australia for medical treatment than Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced that the country’s border security was at risk, and that a fresh wave of would-be refugees would head for Australian shores. The issue of migration has divided Australia and been used by parties on the left and right to drive support. A poll released Feb. 18 indicates Morrison’s stance may be winning back voters for him ahead of the election, which is expected in May.

1. Who are the asylum seekers?

Men, women and children who were intercepted at sea by Australian border-control authorities after paying people smugglers to ferry them to Australia, without visas and often in rickety, unseaworthy boats. The vast majority come from Iran, followed by Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan and Iraq; others are classified as “stateless.” Some have been detained for more than five years. The governments of Nauru and Papua New Guinea, which host the camps for Australia, say about 80 percent of the people they have processed are genuine refugees.

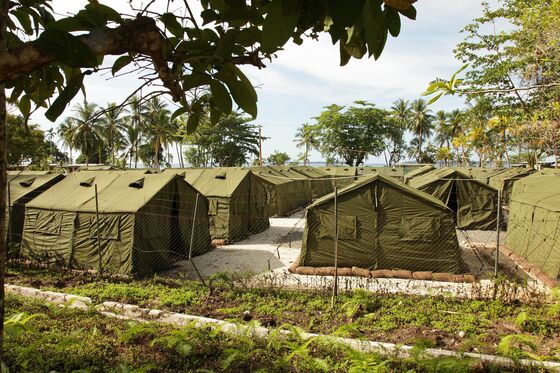

2. Where are they being held?

Almost 600 people were being held on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea in February, and around 420 on Nauru, according to Australian government figures. Nauru, an island nation of barely 10,000 people in Micronesia, and Papua New Guinea accept Australian aid in exchange for hosting the camps. Meanwhile, almost 900 people are already in Australia after being transferred from the camps for medical care before the new medical evacuation law, according to government figures.

3. What’s the history?

Australia has taken a tough stance on asylum seekers arriving by boat since 2001, when then-Prime Minister John Howard refused to let in a vessel carrying more than 400 people, mostly Afghans. His core message, “We will decide who comes to this country,” resonated with voters and helped him win re-election. Howard’s so-called Pacific Solution, where asylum seekers were taken to island camps, lasted until Labor won power in 2007. Labor adopted a more lenient policy and the number of boat arrivals surged -- triggering public concern that the country was losing control of its borders. Then-Prime Minister Julia Gillard reopened the camps on Nauru and Manus in 2012, yet the boats continued to come. A year later Tony Abbott won power for the Liberal-National coalition vowing to “stop the boats.” His government succeeded, often by turning back vessels at sea.

4. Has the policy worked?

The Liberal-National coalition, which is still in power under Morrison, says yes: “Illegal maritime arrivals” have fallen from a high of 20,587 in 2013 to none by 2016. It also says that the policy saves lives as it deters the people-smuggling trade, which saw more than 1,200 lives lost at sea between 2007 and 2012. Yet Australia’s international reputation has suffered, with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees saying open-ended detention is causing the asylum seekers immense harm. The Guardian and other news organizations, citing leaked official reports, have chronicled the conditions in the camps and detailed incidents of self-harm, sexual assault, child abuse, hunger strikes and assault.

5. So where do people in the camps go?

Australia refuses to resettle anyone on Manus and Nauru -- even those deemed genuine refugees -- saying it could spur renewed people smuggling. Instead, it pledged to increase its annual intake through normal channels, which in 2016-17 rose to 24,162 refugees, the highest number since 1980, and started negotiating with other countries to take in people from the camps. So far, only the U.S. has accepted in a deal agreed to by President Barack Obama. His successor, Donald Trump, was angered by what he labeled the “dumb deal” but more than 400 refugees have been re-settled in America under his watch. There’s still four children on Nauru awaiting resettlement in the U.S., and Morrison said on Feb. 19 that 265 applications had been rejected by American authorities, meaning their long-term fate remains in limbo.

6. Why is it back in the news?

Politics. Since coming to power in August, Morrison has struggled to put his own stamp on the leadership and losses in special elections have cost his government its majority. That means he’s at risk of losing votes in Parliament -- as happened when the main opposition Labor and small parties banded together to pass the medical evacuation law. Morrison immediately went on the attack, claiming that it would send a signal to people smugglers that Australia’s tough border-control policy is softening and announced the preemptive reopening of a domestic detention facility. One poll taken during the parliamentary debate suggested that Labor is vulnerable on the issue, setting the stage for another election on border security.

The Reference Shelf

- A QuickTake on political asylum, the world’s most controversial universal idea.

- The Guardian’s collection of stories and opinion pieces about the refugee deal.

- The policies that will decide Australia’s election.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jason Scott in Canberra at jscott14@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Ruth Pollard at rpollard2@bloomberg.net, ;Rosalind Mathieson at rmathieson3@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.