Inequality Was Bad. The Pandemic Is Making It Worse

Inequality Was Bad. The Pandemic Is Making It Worse

(Bloomberg) -- The gap between rich and poor had become a defining narrative of the 21st century long before the coronavirus pandemic put racial disparities and the struggles of low-paid workers in stark relief. Then the killing of George Floyd, a Black American, by a White Minneapolis police officer in May sparked renewed focus on the global debate about the causes of the world’s searing inequalities, why they’ve been tolerated for so long and what can be done to reduce them.

1. What did the pandemic reveal?

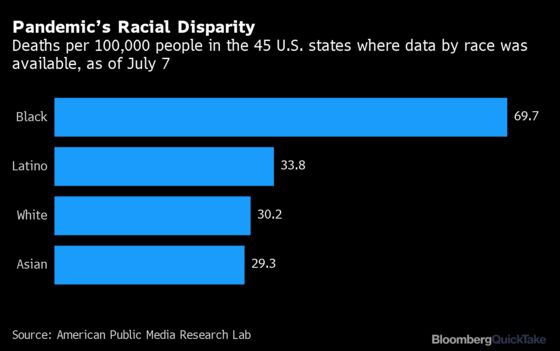

Densely populated poor and minority areas emerged as coronavirus hot spots and suffered disproportionate deaths in hard-hit countries including the U.S., the U.K. and Brazil. While the well-off hibernated in home offices and vacation properties, the essential workers who stock grocery store shelves and staff nursing homes continued to risk their lives on the front lines. Low-wage workers were hit disproportionately hard by job cuts. In the U.S., where unemployment reached the highest since the Great Depression era, pictures of snaking lines at food banks went viral. This all served as a backdrop to Floyd’s death, which touched off the biggest civil rights movement in the U.S. since the 1960s and protests around the world.

2. How did the world respond?

Rich countries mobilized trillions of dollars of pandemic relief for their citizens, while poorer countries in Latin America and Africa struggled to cobble together aid. Governments stepped in to shore up safety nets and health systems. European companies flocked to government programs that kept millions of workers on the payroll for several months. The U.S. government stepped in to provide more robust benefits than ever before, including stimulus checks for households and previously unheard-of provisions such as tax credits for paid sick leave and unemployment insurance for gig workers. Vigorous debates erupted about how rescue funds were being channeled and whether they might — as was widely perceived after the 2008 financial crisis — bail out Wall Street at the expense of Main Street.

3. Will the crisis widen inequality?

It’s looking that way. The World Bank warned that the pandemic could reverse years of progress for the poor in less-developed nations such as India and Nigeria, with as many as 100 million more people expected to fall into extreme poverty. Almost 40% of U.S. job losses were falling on those making less than $40,000, according to Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, who warned that long-term joblessness could be a drag the economy. What’s more, when Black Americans — who are twice as likely to live in poverty — lost jobs they regained them more slowly than Whites. The dichotomy even jarred the investor class in June as the U.S. stock market, aided by the Fed’s relief efforts, surged higher during the same weeks that the Black Lives Matter protests convulsed the nation.

4. What exactly is meant by inequality?

The term has evolved into a catchall for various related ills including poverty, wage stagnation, class division and social disorder. Over the last few years, populist leaders have won office in Italy, Mexico, the U.S. and elsewhere by, in part, tapping into anxieties among people who see the economy as stacked against them. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the elite club of 37 mostly rich countries, says inequality within its member nations is at the highest level in 50 years. The richest 1% earn, on average, nine times the income of the poorest 10%. The world’s billionaires have more than twice the wealth of the rest of humanity combined, a 2019 Oxfam report found.

5. Could the pandemic change things?

Catastrophic events such as the pandemic have historically been a catalyst for reshuffling the economic order. During the Great Depression, with the New Deal, American workers gained a safety net. After World War II they won leverage with employers and higher pay.

6. Isn’t inequality just part of capitalism?

Yes. Capitalism’s profit motive provides incentives for people to act and take risks, which inevitably produces winners and losers. But French economist Thomas Piketty, who ignited academic study with his 2013 book “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” sees discussions about reviving the post-pandemic economy as an opportunity to “change the dominant ideology in terms of how you deal with inequality and how you regulate the economy.”

The Search for Solutions

Tax the rich (more)

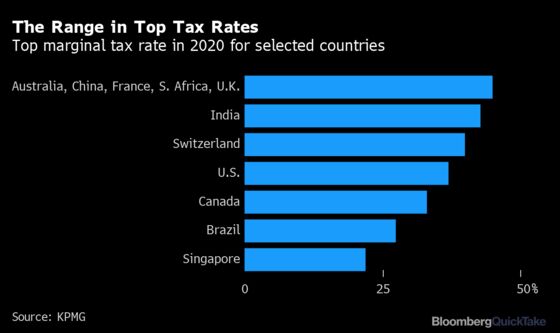

- In the U.S., the Democratic Party, pulled to the left by its invigorated progressive wing, is percolating with proposals to tax the assets, income, inheritances or financial transactions of the affluent. Former Vice President Joe Biden, the party’s presumptive nominee to run against President Donald Trump in the Nov. 3 election, wants to restore the top tax rate to 39.6%, its level before Trump’s 2017 tax cuts dropped it to 37%. Biden also would double the levy on capital gains to 39.6% for taxpayers earning more than $1 million annually. There’s also a global consensus around the need to shutter tax havens. Meanwhile, the pandemic has accelerated plans in several countries to raise revenue through a new “digital tax” on the local sales of rich U.S. companies such as Facebook, Google and Netflix.

Count heads

- Efforts to hire, retain and promote minorities have largely failed to get more underrepresented groups into the highest-paying jobs. Quotas — or preset numerical targets — have a proven track record in Norway and California for getting more women on corporate boards, though the idea raises hackles even with metrics-obsessed executives. Still, with many companies reframing their thinking on inequality, several rolled out hiring targets or tied executive pay to hitting diversity goals. German sportswear brand Adidas AG promised that at least 30% of new U.S. hires would be Black or Latino. BlackRock Inc. committed to increasing its Black workforce 30% by 2024 and doubling the portion of senior leaders from its current 3% share. There are also calls to force more companies to disclose data on the racial and gender makeup of their workforce.

Pay for past wrongs

- Global protests against racism have renewed calls to pay reparations to correct legacy wrongdoings. In the U.K., centuries-old institutions have acknowledged their connections to Britain’s slave trade, with insurer Lloyd’s of London pledging in June to donate an unspecified amount to charities promoting opportunities for Black and minority groups. Proposals to compensate African Americans for the shackles of slavery reach into the trillions of dollars. Interim steps might include federally funded trust funds for Black children that could be tapped in adulthood to pay for education, start a business or purchase a home. In a 2019 Gallup poll, only 29% of Americans supported the idea of paying the descendants of slaves, but that number was up from 14% in 2002.

Reconsider the role of central banks

- In the U.S. and elsewhere, central bankers face questions about how their policies might be disproportionately helping the rich. Even in the strong pre-pandemic economy, minorities struggled to make meaningful progress toward closing gaps in employment, earnings and wealth. Central bankers are considering whether a more relaxed approach to inflation could help narrow labor-market disparities. While Fed officials stress that monetary policy has a limited ability to target things like Black unemployment, they’re pressing lawmakers more openly for government spending and other steps to help ease inequality.

Lighten the load on poorer countries

- More than 100 nations staring down the humanitarian and economic shocks of the pandemic have asked the International Monetary Fund for help. Global leaders backed a moratorium on foreign debt payments for some of the world’s poorest countries to the end of the year; some $730 billion was scheduled to come due this year. Countries including Angola and Pakistan have requested relief. China said it would help African nations facing “the greatest strain.” Ultimately there may need to be a broad program to help poorer countries restructure their loans, similar to the Brady Plan of the late 1980s.

Strengthen unions and boost wages

- The plight of essential workers during the pandemic drew attention to the lack of labor protections and low pay for those who keep society running. Some front-line workers in the U.S. began organizing and agitating for more rights, with walk-outs at Amazon, grocery delivery service Instacart and meat processor Perdue Farms. One possible answer is stronger unions. Many countries are seeing a push for employers to pay a “living wage” that lifts workers out of poverty. Economists are also studying how a higher concentration of big companies in some industries has eroded the bargaining power of workers, and how breakups of dominant firms might help address that.

Provide a universal basic income

- With automation raising fears about how robots might eliminate jobs, politicians and business leaders have floated the idea of a stipend for every citizen, also known as universal basic income. Former U.S. presidential candidate and entrepreneur Andrew Yang made it the central pillar of his platform, calling for a $1,000-a-month “freedom dividend” for every American adult. Cities around the world that have experimented with the idea have had modest success. Finland ended a two-year trial run in 2018 with little fanfare, but preliminary findings showed that the monthly payments improved well-being for participants. The mayor of Stockton, California, which began giving 125 residents $500 a month in February 2019, is trying to expand the idea with a movement called Mayors for a Guaranteed Income.

Reform capitalism

- So-called stakeholder capitalism demands that companies balance the interests of shareholders with those of employees, customers and society. In August 2019, Business Roundtable, an association of U.S. chief executive officers, endorsed the idea. In Europe, company goals have traditionally been closer to that view, with Germany requiring 50% employee representation on large corporations’ supervisory boards, which make strategic decisions. Another model is Scandinavia, which uses high taxes to offset inequality. Governments can also expand targeted programs to address areas where the capitalist system falls short of societal needs, such as building affordable housing.

The Reference Shelf

- A Businessweek cover story on how quotas are getting another look.

- How the pandemic might reduce inequality, or make it worse.

- QuickTakes on proposals for wealth taxes, reparations, debt forgiveness, universal basic income and reforming capitalism.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.