Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence

(Bloomberg) -- Artificial intelligence, or AI, is both the stuff of Terminator-esque, end-of-humanity scenarios and an invisible but steadily increasing part of our daily lives, suggesting what news we should read, for instance, or answering our customer-service queries. Software capable of learning a single narrow task with seemingly superhuman ability is becoming commonplace. AI promises a world of more personalized products and services that are cheaper, faster and free from human error. Many companies think they can cut their costs substantially by deploying AI. The downside of that is the prospect of mass unemployment. And one doesn’t need to feel that AI is “summoning the demon,” in the words of Tesla Inc. Chief Executive Officer Elon Musk, to worry about it eroding privacy and increasing inequality.

The Situation

AI is being used to suggest music you might want to listen to or movies you might want to watch. It’s used to spot attempts at bank fraud and cybercrime. It helps rail companies predict when trains need maintenance and doctors to read X-rays and other medical images. International Data Corp. forecasts that annual corporate spending on AI will grow to about $52 billion by 2021. Meanwhile, the McKinsey Global Institute estimates AI technologies could unlock from $9.5 trillion to $15.4 trillion in annual business value worldwide. With these kinds of numbers, it’s not surprising that many governments, including those of the U.K., France, Canada and the U.S., have come to see AI as an important economic priority. Some countries, such as China, have also made the technology an important strategic goal, taking into account its potential military and intelligence applications. Employee protests over AI’s military potential led Alphabet Inc.’s Google to pull back from a U.S. Department of Defense contract to develop programs to analyze drone footage. Microsoft Corp. called for governments to take action to regulate AI, particularly facial-recognition programs, which have performed particularly poorly with people with darker skin.

The Background

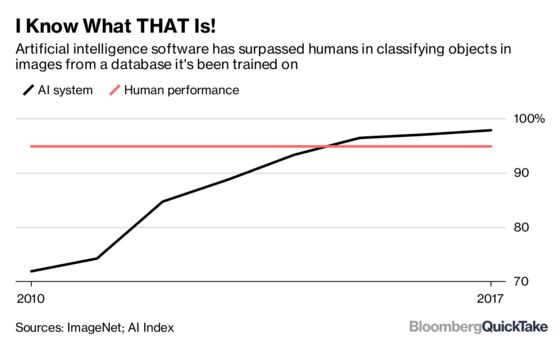

Artificial intelligence is, at its mathematical core, a kind of guesswork: collect a bunch of data and make a stab at the best action to take. This “best guess” can be based on different things: logical rules drawn from human experts, a large number of examples taken from human experience, or a kind of trial-and-error approach that gradually works toward a goal that humans have set. Most AI software has some ability to learn, meaning it adjusts its guesses based on how well or poorly it did before. Computer scientist John McCarthy coined the term in the 1950s, but the field didn’t take off until this century, when technology giants such as Google, Facebook and Microsoft combined vast computer power with deep pools of user data. The most pervasive form of AI these days is called deep learning, a technique in which software is taught to classify something — an image, a loan application — from a very large set of labeled data. But that age-old computing adage — garbage in, garbage out — still applies. If the training data isn’t good — if it doesn’t reflect the real world or incorporates human biases — the AI won’t work as intended or will contain those biases. Software being used to help make decisions on bail, sentencing and parole rated black defendants as more likely to commit future crimes than similar white defendants. In other cases, businesses have denied services to areas with more minority residents.

The Argument

Some experts think AI will create slightly more jobs than it displaces; others foresee AI and related technologies putting as many as 80 million Americans out of work. Even without killing jobs, AI may reinforce inequality: The jobs most at risk, as with most technological innovation, will be lower-skilled. What’s more, by increasing productivity of capital and holding down labor costs, the technology is likely to benefit the owners of capital — in particular, the tech companies that generate the data needed to train robust AI programs. China’s testing of facial-recognition systems that alert authorities when targeted people leave a designated area raises questions of an AI-powered police state. Many of the companies at the forefront of AI research have banded together in organizations, such as the Partnership on AI, that are focused on issues around fairness and transparency, safety and AI’s impact on jobs. At the same time, the biggest concrete concern is that today’s AI is, ironically, too often frustratingly stupid — stumped by situations a small child would ace and lacking what’s generally referred to as common sense.

The Reference Shelf

- In 2006, for the 50th anniversary of the coining of the term “artificial intelligence,” AI Magazine published this “Brief History.”

- The Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, founded by late Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, argues that fears of AI’s effects are exaggerated; the Future of Life Institute explores them.

- The 1943 paper that laid the groundwork for neural networks, by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: John O'Neil at joneil18@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.