‘Coronabonds’ Could Bail Europe Out, Tie It Together

The economic crisis triggered by the spread of coronavirus has led to a renewed push for a never-before-tried financial tool

(Bloomberg) -- Like every other part of the world, Europe is facing an economic crisis, unleashed by a global pandemic. What’s unique in the region is how the crisis has led to a renewed push for a never-before-tried financial tool -- now aptly renamed “coronabonds.” While politically divisive, these pooled debt securities could help overcome one of the biggest hurdles faced by the European Union: how to drive more financial integration and risk-sharing across the continent.

1. What are ‘coronabonds’?

Pre-coronavirus they were known as euro bonds, and they were something many EU leaders have argued for since the creation of the euro in 1999: a shared debt instrument to finance borrowing, where the money can be directed to the countries that need it most. National governments currently sell their own debt to fund projects and annual budgets, but do so at wildly varying costs. Germany can effectively be paid to borrow, due to its impeccable credit rating and tight spending rules, while Italy -- with its less-stellar credit rating -- has to pay a higher interest rate of at least a full percentage-point more. Though the idea has failed to garner sufficient support, a coronabond could “mutualize” risk among nations, possibly cutting borrowing costs.

2. Why now?

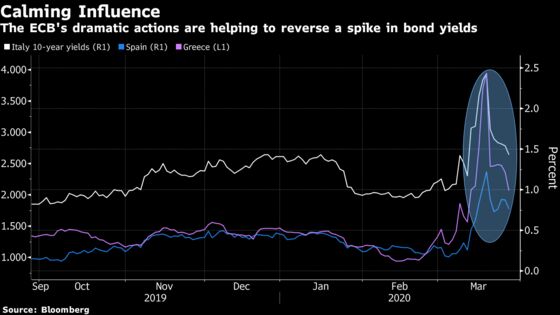

While the 19-member euro area has long battled with how to narrow differences between rich and poor members, the coronavirus has exposed those inequalities like never before. Some of the most indebted nations such as Italy and Spain have been hardest hit, with deaths spiraling into the thousands. At the same time, the European Central Bank has pledged to help ease the crisis by purchasing more than 1 trillion euros ($1.1 trillion) of bonds this year through its so-called quantitative easing programs. It also scrapped its self-imposed purchasing limits. But it may still need to take further steps to calm the volatile markets for government bonds. A new debt instrument could allow the central bank more flexibility. President Christine Lagarde is a huge proponent. Italy is, too.

3. What’s the issue?

Germany. Europe’s economic powerhouse has long opposed the idea of euro bonds, wary that it could be on the line for the financing of poorer nations in Europe’s south, and 57% of the population is supposedly against the idea. It’s less than a decade since the region’s sovereign debt crisis threatened to sink the common currency. Back then, with Greece requiring a series of bailouts, Germany resisted calls for euro bonds. Those fears have come back to the surface with finance ministers across the bloc squabbling over even a hint of possible joint issuance to come. Any move now to issue such debt would have to be approved by Germany’s legislature and there are doubts over whether Chancellor Angela Merkel would be able to secure the required support. Proponents of coronabonds contend the current crisis is an external shock that requires a joint solution.

4. How would coronabonds work?

The idea is for a jointly backed bond sale of up to 1.5 trillion euros that would fund government action to contain the virus and reboot euro-area economies. The leaders of Spain, Italy, France, Portugal, Greece, Belgium, Luxembourg Slovenia and Ireland said the bloc needed to work on such an instrument of sufficient size in order to ensure “stable long-term financing for the policies required to counter the damages caused by this pandemic.” Germany and the Netherlands were notable absentees. There’s no clear understanding of whether such a bond sale would be a one-off measure or a gateway to recurring sales. But they could possibly help the ECB find more bonds to buy, given there are still constrained by the capital key, which dictates purchases according to the size and population of each country.

5. Why the resistance?

Richer countries like the Netherlands, Austria and Germany have long complained that their southern neighbors don’t use the good times of solid economic growth to put their houses in order, arguing it’s not their fault those countries lack the means to battle their way out of a crisis. The “moral hazard” argument -- that bailouts encourage further bad behavior -- has long been a roadblock. This time, though, the damage was not caused by profligate spending but by an unforeseen global health crisis.

6. What would coronabonds mean for existing debt?

That’s unclear. Borrowing costs of the various member nations would probably converge, with yields on German bonds rising and those of riskier nations’ debt such as Italy’s falling. Much would depend on the size of the program, though. For James Athey, a money manager at Aberdeen Standard Investments, the first tranches are likely to be small so Germany could retain control over its fiscal liabilities. Longer term, Athey says holders of Italian government debt could lose out if coronabonds were judged as being superior, meaning that the holders of those securities would get paid out first in the event of any default.

7. What’s the alternative?

Governments can of course sell their own debt to fund crisis-response measures, and the ECB’s huge bond-buying program will likely keep borrowing costs in check. But spending domestically to combat a disease that does not respect national borders may not be the most efficient strategy. EU finance ministers have agreed on a 540 billion-euro package of measures that include a joint employment insurance fund and as much as 240 billion euros from the European Stability Mechanism. Ministers have also agreed to work on a temporary fund that would help kick start the recovery and will be financed by “innovative” instruments. Joint issuance could, in theory, be one way of doing it. Still, much remains undecided, including what strings may be attached to any support. Countries may also be reluctant to take the money, worried they’ll be stigmatized as weak and potentially subjected to demands for changes in local regulation and other economic reforms. Another tool in the ECB arsenal is its crisis-era program known as Outright Monetary Transactions, which has never been used. Under that program, the ECB could theoretically buy unlimited amounts of sovereign bonds in the secondary market from currency-bloc members that have signed bailout agreements with the ESM.

The Reference Shelf

- How the coronavirus is testing the EU’s unity.

- A Financial Times editorial on why coronabonds are unlikely to gain support.

- Why the ECB’s OMT program is controversial, too.

- Europe agrees on rescue package, while the ECB scraps bond-buying limits.

- Berenberg Chief Economist Holger Schmieding outlines the case for coronabonds.

- QuickTakes on the euro’s existential crisis, and Europe’s tricky history with QE.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.