Israel Annex the West Bank? How a Taboo Idea Got Real: QuickTake

Annex the West Bank? How an Idea Lost Its Taboo in Israel: QuickTake

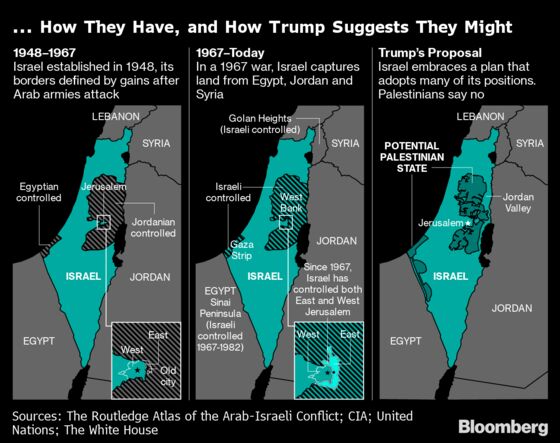

(Bloomberg) -- In 1967, Israel conquered the West Bank, land Palestinians see as the core of a future state of their own. Ever since, Israel has controlled the territory but without claiming to own it. Now the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu intends to annex as much as 30% of the West Bank, making it part of the sovereign state of Israel. The plan, which only a few years ago was regarded as a fringe idea within Israel, reflects changes in the country’s politics and in its relationship with the U.S. as well as an expectation, possibly false, of a mild reaction from the Palestinians’ traditional supporters in the Arab world.

1. What’s the West Bank?

It’s a landlocked block of territory west of the Jordan River where 2.6 million Palestinians live. An additional 300,000 reside in east Jerusalem, and 1.9 million live in the Gaza Strip, a sliver of Mediterranean coastline between Israel and Egypt. These areas are among the lands captured by Israel from neighboring Arab countries in the 1967 Middle East war. The West Bank is also home to more than 400,000 Jewish Israeli settlers. They moved to the West Bank after 1967 because they received government incentives, see it as the cradle of Judaism, view it as a strategically valuable area Israel must keep or some combination of those factors.

2. What does Israel plan to annex?

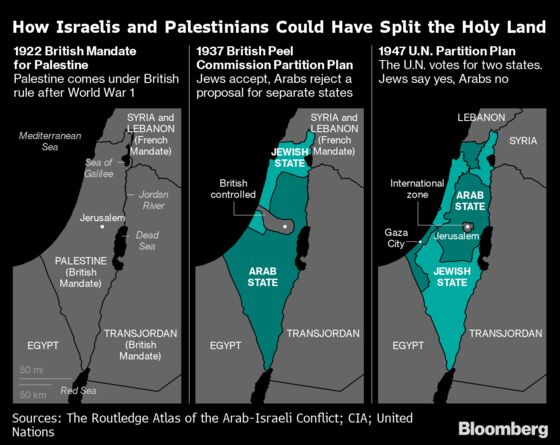

Netanyahu’s government wants to annex the roughly 130 officially recognized Israeli settlements plus more than 100 settler outposts sprinkled throughout the West Bank, as well as the Jordan Valley, a strip along the territory’s eastern frontier. Israeli security officials argue that the valley serves as a necessary bulwark against potential attacks of the kind that occurred in 1948, when Arab countries assaulted Israel after rejecting a United Nations plan partitioning the British-ruled Holy Land. However, Netanyahu could pare that back to annexing major settlement blocs or a symbolic piece of land in the Jordan Valley as an initial step.

3. Why now?

Netanyahu has called his annexation plan a “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” That’s because it has unprecedented support from Israel’s most important ally, the U.S., so long as the American president is Donald Trump, who faces re-election in November. Under Trump’s vision of a final peace deal, unveiled in late January, Israel would keep the settlements and the Jordan Valley. The Palestinians, who lay claim to all of the West Bank, flatly rejected the plan, but U.S. officials gave Israel a green light to annex those areas anyway, though they later asked for a mapping committee to study the issue. Previous U.S. administrations have taken the position that any new borders should be negotiated and agreed by the two sides. Under Trump, the U.S. has broken other longstanding policies to recognize Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem, which it previously considered a contested city, and Israel’s annexation of the southern part of the Golan Heights, the strategic plateau it captured from Syria in 1967. Leaving a personal legacy may also be on longtime premier Netanyahu’s mind, as he stands trial over corruption charges.

4. How do Israelis view the annexation plan?

An April poll by the Israel Democracy Institute indicated more Jewish Israelis support annexation than oppose it, though only a minority expected such a plan to actually be implemented in the coming year. The peace camp in Israel has diminished in size and strength since the Oslo accords of the 1990s opened the possibility of two states living side by side. The outbreak of the Palestinian uprising against Israel in late 2000 after years of troubled negotiations took a toll. And after the militant Islamist group Hamas took over the Gaza Strip in 2007 and used it to fire rockets into Israel, more Israelis balked at the idea of ceding the West Bank to Palestinian control. The last round of Israeli-Palestinian negotiations foundered in 2014.

5. How have neighboring states responded?

Some commentators had anticipated a relatively muted reaction. That’s because in recent years other matters, including the wars in Iraq and Syria, battles against Islamic State and conflicts over Kurdish aspirations, have pushed the Palestinian issue down on the regional agenda. And the Gulf Arab countries have been more focused on combating Iran -- an area of alignment with Israel. However, the Arab League rejected the Trump blueprint on which Netanyahu’s annexation plan is based. With Netanyahu planning to start annexation as soon as July 1, individual Arab governments have warned against it. Most strikingly, Yousef Al Otaiba, the United Arab Emirates ambassador to the U.S., published an op-ed in Hebrew in a leading Israeli newspaper arguing that “annexation will certainly and immediately upend Israeli aspirations for improved security, economic and cultural ties with the Arab world and with UAE.” Neighboring Jordan, one of two Arab states to sign a peace accord with Israel, said that annexation would have a dire impact on its relations with Israel. Other Mideast states from Saudi Arabia to Turkey have slammed the planned move.

6. What would annexation mean?

In terms of practical realities, not much. Under the Oslo accords, Palestinians already have only limited self-rule in the West Bank, and Israel maintains overall security control and exclusive jurisdiction over the settlers. As it is, the presence of settlements and of Israeli forces in the West Bank makes everyday life difficult for Palestinians. Barriers, fences and buffer zones meant to secure settlers restrict the freedom, movement and commerce of Palestinians.

7. So what would it change?

Prospects for a future Palestinian state. Before peace talks broke down, Palestinian representatives had agreed that in a final deal, the border would be redrawn so that Israel would keep many settlements -- in exchange for territory elsewhere, though not as envisioned in Trump’s plan. With all of the settlements cut out of the West Bank, a future Palestinian state would be a disjointed patchwork of enclaves. That could impede the development of infrastructure and the movement of people and goods, putting that state’s viability in question. With the Jordan Valley removed as well, the state would be completely surrounded by Israel and thus captive to it.

8. What leverage do Palestinians have?

Palestinian militants have long sought to influence Israel’s behavior through acts of violence against Israeli civilians. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas has announced that agreements providing for security cooperation between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, the limited self-rule government established under the Oslo accords, are no longer in force. That potentially hobbles Israel’s ability to thwart attacks and endangers the mutual goal of keeping Hamas from wresting control of the West Bank from the Palestinian Authority as it did Gaza. The Palestinians have also threatened to declare an independent state and seek international recognition.

9. Do the Palestinians have legal recourse?

Annexing territory in the West Bank would provide fodder at the International Criminal Court, which has said it intends to investigate Palestinian claims that Israel committed war crimes in conflicts between the two sides. The International Court of Justice, a branch of the United Nations, concluded in 2004 that the West Bank and Gaza Strip are occupied territories. That means the Fourth Geneva Convention, an international treaty governing conquered lands, applies to them, a position supported by an overwhelming majority of UN members in a 2017 vote. Under the 1949 convention, which protects civilians in times of war, states are precluded from changing the status of territories they occupy, for instance through annexation. Israel regards both courts as biased against it and takes the position that the West Bank, which it captured from Jordan, is “disputed” rather than “occupied” because Jordan’s own annexation of it in 1950 wasn’t internationally recognized.

The Reference Shelf

- Related QuickTakes on why the two-state idea for Israel and Palestine is fading, Israeli settlements, and the U.S.-Israel relationship.

- A Bloomberg Businessweek feature on how real estate prices in Jewish settlements have jumped in anticipation of annexation.

- A Bloomberg profile of the the U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman, who has shifted American policy toward settlers.

- Former Mideast peace negotiator Aaron David Miller’s book on the U.S. role in Arab-Israel negotiations.

- Philosopher Micah Goodman breaks down Israel’s dilemma in his book Catch-67.

- The New Yorker’s 2013 profile of rising stars in Israeli politics that brought visibility to the annexation idea.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.