Air Pollution

Air Pollution

(Bloomberg) -- From Beijing to Berlin, New Delhi to London, improving air quality is a matter of life and death. The World Health Organization estimates that outdoor air pollution kills 4.2 million people each year. It leads to billions of dollars spent on medical care and missed work and causes widespread illness, particularly among the very young and the very old. It’s a problem that knows no borders, though it’s felt most severely in the developing world and in cities. And it’s a challenge scientists increasingly see aligned to the fight against climate change, since both issues are — as the United Nations puts it — two sides of the same coin. New methods to detect pollution and different approaches to legal challenges are some of the ways that people are fighting back against what the head of the WHO has called the “new tobacco.”

The Situation

More than 90% of people live in places where WHO air quality guidelines are breached. That means most humans are overexposed to the microscopic particles and gases emitted by cars, factories and power plants that can lead to heart and respiratory diseases and cancer. Diesel vehicles soared in popularity in Europe partly because of their lower carbon emissions, but the nitrogen dioxide fumes they produce have made polluted air the “biggest environmental risk to public health,” according to U.K. authorities. It’s now illegal to drive some diesel cars in Madrid, Paris or Brussels, while Germany has banned older diesel automobiles and Bristol in the U.K. will impose a complete city-center ban from 2021. In parts of the developing world, rapid industrialization aimed at lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty has come at the expense of air quality. In 2013, a rare public outcry on Chinese social media pushed authorities to tighten environmental regulations, close some coal-fired facilities and switch millions of homes and businesses from coal to cleaner-burning natural gas. Still, air pollution kills an estimated 1.1 million Chinese a year and costs the economy $37 billion, a 2018 study found, and the country continues to build power plants that burn coal. In India, industrial and vehicle emissions combine with the illegal burning of farm stubble to leave cities such as New Delhi shrouded in a blanket of thick smog each winter (2019 ranks as one of the worst years for the capital). India is now home to seven of the world’s 10 most-polluted cities.

The Background

Air pollution has been killing people since the Industrial Revolution, and the worst excesses today are no worse than London’s pea soup in the 19th century or Japan’s smoggy 1960s. Acid rain that destroyed forests in the 1970s prompted 50 countries to reduce sulfur emissions; their agreement still serves as a blueprint for how scientists and policy makers can work together to improve the environment. Innovations in engines and the use of catalytic converters, for instance, reduced vehicle lead emissions in the U.S. by more than 90% between 1980 and 1999. A combination of urbanization, laxer regulations, soaring fossil fuel consumption and rapid economic transformation has stoked the problem in developing countries. Air quality is an issue that brings people out into the streets — as witnessed in recent years by protests in China, Mongolia and India. Frustrated at the lack of enforcement of emission standards in South Africa, environmental groups there are suing the government. The U.K., France, Germany, Hungary, Italy and Romania have received final warnings to improve air quality from the European Court of Justice following legal action by the environmental charity ClientEarth. The same organization secured a court ruling in 2019 that allows European Union citizens to challenge how authorities monitor pollution.

The Argument

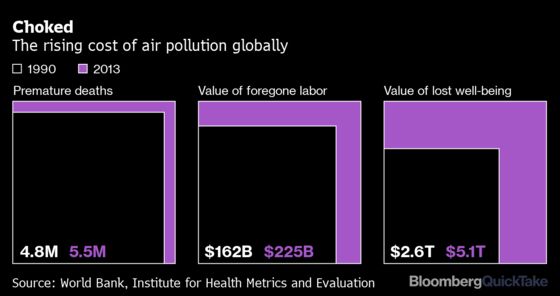

Advocates for urgent action contend that cleaning up the air makes economic sense as well as being the right thing to do; health-related savings outweigh the costs of cleaning the air to the tune of more than $1 trillion a year, according to one United Nations estimate. While climate change is seen as a global issue, air pollution is viewed as a local problem, meaning poorer countries can’t rely on support from richer ones to solve their problems. Those nations often must balance the need to promote economic growth (for instance by building cheap coal-fired power plants) with public anger over pollution’s health impact. Enforcing anti-pollution and related regulations is among the most effective ways to make a difference, as evidenced by Indonesia’s success from 2016 to 2018 at cracking down on the agricultural burning of forest that sporadically blankets parts of Southeast Asia in a thick haze. Brazil's softening of enforcement efforts led to record levels of forest fires in the Amazon in 2019, when there were also setbacks in Indonesia partly caused by drier weather. Leaps forward in sensory technologies are giving local regulators and citizen scientists the ability to generate more and better data that helps pinpoint and track the industries and plants that are sources of danger. Such advances provide the intelligence to address pollution in real time and the ammunition to force action through the legal system against those neglecting their responsibilities.

The Reference Shelf

- The World Health Organization’s air pollution map.

- Air pollution deaths may be much higher than estimated, according to a report in Science Daily.

- The World Bank’s assessment of pollution’s cost.

- More regulation is required, says Bloomberg Opinion writer Karl W. Smith.

- In the U.S., African-Americans are hit especially hard by air pollution even though they cause relatively little of it, writes Bloomberg Opinion’s Cass R. Sunstein.

- QuickTakes on deforestation, smog in India and China, California’s anti-pollution push and climate change.

- News on air pollution, courtesy of the UN.

- Climate-change warriors’ latest weapon of choice: litigation.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Grant Clark at gclark@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.