Affordable Housing

Affordable Housing

(Bloomberg) -- Cities around the globe are facing a stark reality: There are not enough affordable places for people to live. Housing in most big urban areas is now considered out of reach for the average worker, fueling a growing sense that a decent home has become a privilege traded among the “haves,” impoverishing the “have-nots.” Thorny questions abound: Should new luxury apartments in London — many owned by foreigners — be allowed to lie empty, while thousands of people sit on waiting lists for affordable homes? If migrants streaming into Beijing for a better life turn to dangerous, illegal dwellings, where will they go when those places are demolished? The worst may be yet to come. The share of the world’s population living in cities is projected to reach 68% by 2050, up from 55% today.

The Situation

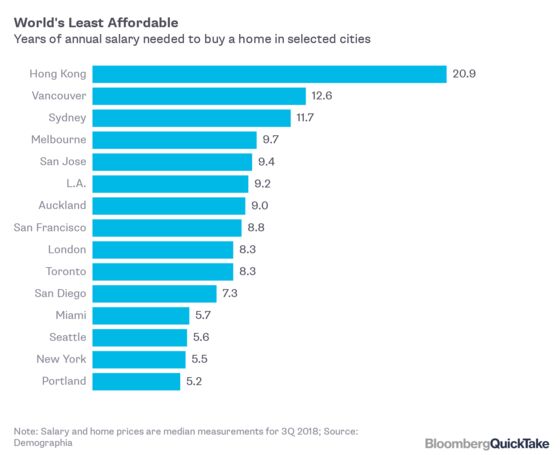

Rising prices have made homes in 58% of major cities significantly unaffordable, compared with less than half five years ago, according to an annual study by research firm Demographia. That means it costs more than 4.1 times median annual income to buy a median-priced home. A typical apartment in Hong Kong now costs HK$7,169,000 ($916,225), which has helped fuel political protests. Other hotspots include Berlin, where a grassroots campaign to nationalize housing led to a radical plan to freeze rents for five years. Vancouver adopted North America’s first tax on empty homes, and cities from New Orleans to Athens are grappling with the impact of Airbnb-type rentals that effectively set aside thousands of units for tourists. New York City installed its most sweeping tenant protections in decades in 2019, capping rent increases and eliminating loopholes. The move came after Amazon.com Inc.’s expansion plans there were thwarted by community groups who feared residents would be priced out of the city. More governments have pledged to step up building: India aims to construct more than 40 million homes by 2022. Big companies have also responded. Alphabet Inc.’s Google pledged $1 billion to help create 15,000 homes in California. Still, that’s a drop in the bucket in a state with an estimated annual shortfall of 180,000 units.

The Background

In the 19th century, farmworkers who flocked to cities crowded into squalid quarters near factories. Now, technology, health care and finance companies are pulling in throngs of white-collar workers, gentrifying neighborhoods close to transit links. That’s displacing teachers, nurses, firefighters, office cleaners and other essential workers, aggravating inequality. There's also more competition from international and institutional investors, who've shifted money into real estate after a decade of low interest rates reduced returns on other assets. Supply hasn’t kept up. Since the 1980s, the U.S. and U.K. have scaled back investment in state-funded homes. These governments have largely gotten out of the business of constructing public housing and instead encouraged development by nonprofits and private companies with subsidies or tax incentives. Many cities began to require developers building luxury homes to set aside a small portion of units for lower-income buyers or renters. It hasn’t been enough. In the U.S., the number of low-rent units has shrunk by 4 million since 2011, and about 47% of renters spend more than 30% of their income on housing. That’s contributed to a spike in homelessness in some of America’s richest cities.

The Argument

Critics of rent control say it’s a crude solution that can backfire, scaring away investment and causing buildings to fall into disrepair, often resulting in fewer affordable units. But advocates say price caps can keep neighborhoods stable and slow the rate of gentrification. Private developers say they often have no choice but to focus on expensive units because labor, materials and especially land have gotten so pricey. Local governments, they say, could help by easing zoning rules, relaxing building codes and overruling “not-in-my-backyard,” or NIMBY protests that stymie projects. One controversial solution gaining support is to force more neighborhoods to accept higher density across the board, an approach long favored by urban planners. In 2018, the city of Minneapolis became one of the first and the largest in the U.S. to end single-family zoning, which means developers will be able to build homes for two or three families on each plot.

The Reference Shelf

- Research firm Demographia publishes global comparisons on the affordability of homes.

- A Bloomberg series on affordable housing visited Spain, Finland, Portugal and Berlin.

- Bloomberg Businessweek explained the fight in Minneapolis over zoning for single-family homes.

- A report on the state of U.S. housing from Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies.

- A QuickTake on Hong Kong’s sky-high home prices.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Leah Harrison at lharrison@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.