What to Know About Recessions, Including the Next One

Is a recession inevitable?

(Bloomberg) -- Economists now see a one-in-three chance that the U.S. economy is headed into recession in the next year, following its longest expansion in history. Germany, the biggest economic engine in the European Union, is on the brink. Worries are growing even in Australia, which has gone a remarkable 28 years without a downturn. So much time has passed since the Great Recession of 2007-2009 that many adults haven’t experienced an economy that’s contracting rather than growing in their working lives. But slowing global growth and the U.S.-China trade war, among other strains, have flamed fears that the next recession is around the corner.

1. Is a recession inevitable?

Eventually, yes -- recessions follow expansions, and vice versa. The real questions are when the recession hits, how long it lasts and how severe it is.

2. Does a U.S. recession mean a global recession too?

Not necessarily. The U.S. has experienced 11 recessions since the end of World War II, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research. The International Monetary Fund counts only four global recessions, tracing back to 1960. Neither organization uses the dictionary definition of a recession, a period when economic output contracts for two straight quarters. NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee, which makes the official U.S. determination, considers such additional factors as employment, industrial production and income and typically takes about a year to make the call. The IMF, in labeling global recessions, looks for a decline in inflation-adjusted per-capita GDP that’s backed up by weakness in industrial production, trade, capital flows, oil consumption and unemployment.

3. What triggers recessions?

Before World War I, “relatively frequent” recessions “stemmed from a wide range of private-sector-induced fluctuations in spending, such as investment busts and financial panics,” according to a paper by Christina Romer, who led President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers. The so-called Great Moderation, a roughly 25-year period of relative stability around the globe beginning in the mid-1980s, spawned the view that modern-day recessions don’t happen without “an unexpected shock to the economy that has lasting consequences, such as a sharp increase in oil prices” -- a cause of U.S. downturns of the 1970s and 1980s -- or “accumulated imbalances that can no longer be ignored.”

4. What constitutes an imbalance?

The dot-com bubble that grew in the late 1990s and burst before the 2001 recession was one example. So was the massive buildup in the subprime-lending industry that preceded the so-called Great Recession of 2007-2009. Many Americans took on mortgages they couldn’t afford, which were packaged to investors as top-quality securities.

5. What makes a recession mild or severe?

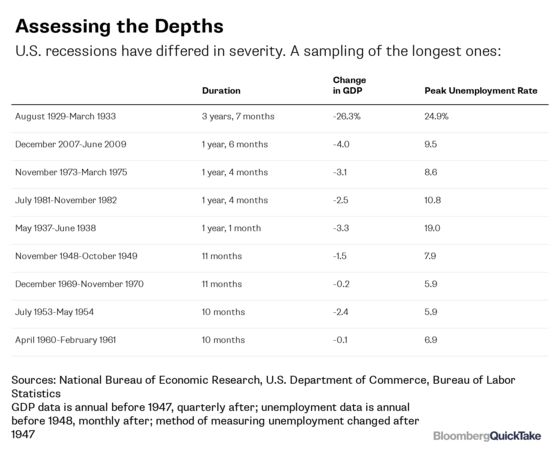

Its duration, for one thing. The 2007-2009 recession lasted 18 months, making it the longest since the Great Depression. The recession of 1980, by contrast, lasted just six months. Other measures of a recession’s severity are how much the economy contracts and how bad unemployment gets. The worst recessions tend to be those paired with some sort of collapse in the financial system, as happened in the U.S. in 2007 and 1929. Researchers have considered whether the duration of an expansion influences how bad the subsequent recession is. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland researchers found little evidence of that, but they did find reason to think severe recessions (like the one that ended in 2009) spawn strong expansions. Another driver of a recession’s severity is how broadly the economy suffers a contraction. The relatively short and mild 2001 recession, for instance, was largely confined to the tech sector, with modest fallout to the rest of the economy.

6. So will the next recession be a bad one?

It’s impossible to know. On the positive side, American households are carrying less debt, and an increase in mortgage refinancing has put more cash in consumers’ pockets. Also, as in 2001, the current strains are (so far) mostly confined to one sector -- manufacturing. Pessimists would note that interest rates are already low, meaning the Fed has less conventional ammunition to combat a downturn, and the U.S. budget deficit is expected to hit a dizzying $1 trillion next year, which could hamper how much fiscal stimulus the government could provide. On the global level, the World Economic Forum warned at the start of the year that the “global debt burden,” at around 225% of GDP, “is significantly higher than before the global financial crisis.”

7. Can anything be done now to ease the next recession?

Countries around the globe are weighing monetary and fiscal stimulus options. In Germany, which already has had one quarter of shrinking GDP, there are signs that a rigid adherence to balanced budgets may give way to bonus-like incentives to encourage home improvements, short-term hiring and social-welfare programs. Even Australia and New Zealand, holdouts from the extreme monetary policies spawned by the financial crisis a decade ago, are thinking of jumping in.

The Reference Shelf

- Leaders around the world are talking about economic stimulus.

- Germany is debating a wealth tax even as recession fears grow.

- Could Hong Kong protests be the shock that triggers a global recession?

- Why a recession in 2020 is no sure thing.

- The American Institute for Economic Research examined “the changing nature of recessions.”

- Christina Romer’s paper on business cycles.

- A U.S. manufacturing recession is already here, writes Bloomberg Opinion columnist Brooke Sutherland.

To contact the reporter on this story: Reade Pickert in Washington at epickert@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Scott Lanman at slanman@bloomberg.net, Laurence Arnold

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.