Liquefied Natural Gas

Liquefied Natural Gas

(Bloomberg) -- Natural gas has a lot going for it. It burns cleaner than other fossil fuels, producing about half the carbon dioxide of coal. Thanks to new discoveries and the U.S. shale boom, it’s cheap and plentiful. But there’s a catch: Gas is tricky to transport from the often-remote fields where it’s found to where it’s needed — places such as China, India and South Korea. In many regions, pipelines simply aren’t practical. The solution? Turn the gas into a liquid by super-cooling it to minus 162 degrees Celsius (minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit). Liquefied natural gas, known as LNG, gets loaded onto massive ships and transported around the world. This high-tech process has transformed natural gas into a mobile, freely traded commodity and reshaped the politics of global energy.

The Situation

America’s natural gas is now available on world markets, thanks to the gas released through hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, and exported as LNG. The fastest-growing buyer has been China, though it’s now threatening to impose a 25 percent tariff on U.S. LNG amid an escalating trade war. In Europe, shifting to LNG is critical for countries such as Lithuania and Poland that are looking to escape the pipeline politics of buying gas from Russia. LNG is also helping to offset dwindling gas output from the North Sea. Demand has improved after a 50 percent price drop since 2014 in a key global benchmark made the once-premium fuel more competitive with dirtier oil and coal. And while much of the talk just a year ago centered around a massive supply glut, soaring demand from China and emerging importers such as Pakistan has sparked new warnings of a coming shortage if more multibillion-dollar projects aren’t built soon. More countries are trading in LNG, with 40 nations importing it and 19 exporting at the end of 2017. Jordan and Egypt are turning to LNG to fuel electricity generation as prices fall and import terminals become less expensive to build. The gas is also used to power ships and trucks.

The Background

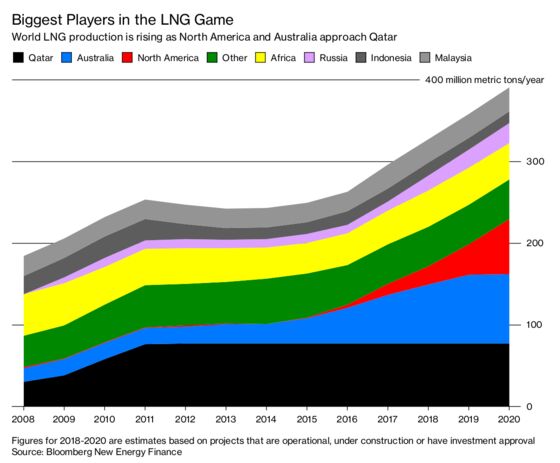

Commercial LNG shipments began in 1964 with regular cargoes from Algeria to the U.K. and France. The global fleet now includes more than 400 vessels, the biggest as long as almost four American football fields. LNG is a capital-intensive business: Tankers cost about $250 million, and building a terminal for import or export is a multibillion-dollar undertaking. Qatar is the world’s biggest producer of LNG, with about three-quarters of the fuel sold to energy-poor Asian countries such as Japan and Korea. Natural gas supplies about a fifth of world energy, and its use is growing; LNG accounts for half of new gas capacity. China’s move to limit air pollution is expected to turn it into the world’s biggest importer by 2019, and the nation will account for more than a third of global growth through 2023. More projects are being considered to ship gas from large fields in Mozambique and Iran.

The Argument

More nations have shifted to LNG as a way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Demand for the fuel will be driven by how quickly countries turn to gas in a bid to displace coal as the largest source of power generation. Big oil companies have pushed into LNG as a way to embrace cleaner energy and tap new markets. Shell’s $53 billion acquisition of BG Group in 2016 — the industry’s biggest deal in a decade — included a fleet of tankers and made the Dutch giant the world’s largest LNG trader. But for all its relative cleanliness, gas producers still leak methane during the production process, which can be a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. That’s part of the reason why many environmentalists consider LNG a “bridge fuel” — or a placeholder energy provider until renewables such as solar and wind become more feasible.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg News explored how the market for LNG might survive a U.S.-China trade war.

- Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects the global LNG market through 2030.

- Businessweek examined how Shell was shifting to gas to adapt to climate change.

- A video from Shell explains the chemical process to make LNG.

- The International Gas Union publishes an annual report on LNG.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Leah Harrison at lharrison@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.