Sanctions

Sanctions

(Bloomberg) -- When diplomacy failed, war used to be the next option, the continuation of politics by other means. Today, when persuasion doesn’t work, big powers often turn to economic combat as their first resort. Sanctions occupy a messy zone between condemnations and military strikes. Hard to organize and uncertain in impact, they can hurt innocent citizens and legitimate businesses. They tend to be more effective when a group of countries comes together to target an offending state. That, of course, requires agreement on who deserves punishing.

The Situation

In August, the U.S. began reimposing sanctions on Iran that it had lifted as part of a 2015 multilateral deal that eased sanctions on Iran in exchange for restrictions on its nuclear program. President Donald Trump pulled the U.S. out of the agreement, saying he wanted to put pressure on Iran in order to negotiate a new deal with tougher terms. The U.S. also imposed unprecedented sanctions on a NATO ally, Turkey, in response to its refusal to release an American pastor the U.S. says is unjustly detained. In 2017, U.S. lawmakers approved fresh sanctions on Russia that sent the two powers into a new spiral of tensions. The sanctions were retaliation for Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The European Union objected to a provision in the U.S. plan that could harm European energy companies doing business with Russia. As North Korea ramped up its nuclear weapons and missile programs, the U.S., China and the United Nations Security Council expanded sanctions against it, contributing to a sharp contraction in the country’s economy in 2017. In 2018, North Korea agreed to the “complete denuclearization” of the Korean peninsula, though it’s unclear what the country would require of the U.S., which provides a so-called nuclear umbrella to guarantee the safety of allies South Korea and Japan.

The Background

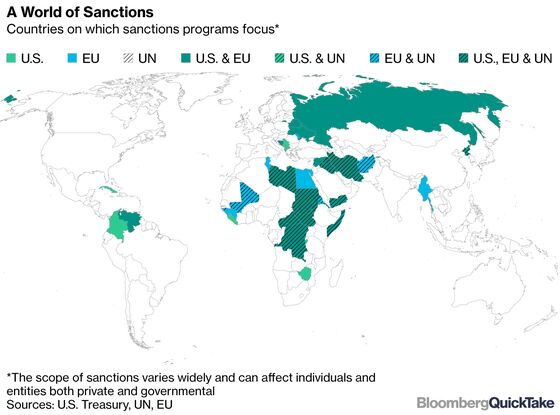

The first documented use of economic pressure for political ends dates to ancient Greece (the city-state of Megara banned trade with Athens in 432 B.C.). The U.S. Treasury first employed sanctions before the 1812 War against Britain. Woodrow Wilson was the first modern leader to promote financial pressure as an alternative to combat. Use of the tactic has grown dramatically this century. The UN had 14 sanctions programs in place in mid-2018, one fewer than in 2015 when the number reached its highest level. The EU regularly imposes its own sanctions. No modern nation has wielded economic weapons more than the U.S., which restricted imports, exports, investments and other financial transactions more than 110 times in the 20th century to try to change policies, end weapons programs or topple a government. The U.S. Treasury Department became a prominent national security player after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Its self-described “guerrillas in gray suits” manage 28 sanctions programs that target governments, individuals, terrorist groups or criminal organizations in about two dozen countries.

The Argument

Sanctions against Russia for its 2014 seizure of Crimea and support for separatists in eastern Ukraine show how tricky they are to apply successfully. The U.S. and EU have kept the sanctions in place hoping to enforce a ceasefire negotiated in February 2015. But so far the pressure has been insufficient to compel Russia to ensure its allies fully implement the accord. Democratic or quasi-democratic states that care about international opinion and rely on global trade and finance are likeliest to respond to sanctions, while isolated authoritarian regimes often don’t. The most effective sanctions are crippling ones imposed by multiple countries; the global boycott of South Africa over its apartheid policy in the 1980s led to elections that ushered the black majority to power. Global measures against Iran squeezed its economy and propelled its leaders to return to talks that produced the agreement limiting the country’s nuclear program. The worst case of unintended consequences may be the U.S. oil embargo on Japan that unleashed a chain of events leading to the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Sanctions on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq were criticized as toothless, indiscriminate and corrupt; in retrospect, they were proven to have cut off funding for his weapons of mass destruction.

The Reference Shelf

- A history of sanctions published by Columbia International Affairs Online.

- Foreign Policy magazine explains how “a blunt diplomatic tool” morphed into a “precision-guided” weapon.

- Three economists assessed the effectiveness of sanctions in a 2009 book, “Economic Sanctions Reconsidered.” A table looks at cases since 1914; another covers post-2000 episodes.

- Juan Zarate, a former Treasury official, describes how the U.S. used post-9/11 financial weapons against terrorists, criminals and rogue regimes in his book, “Treasury’s War.”

Indira Lakshmanan contributed to the original version of this article.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Lisa Beyer at lbeyer3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.