Greece’s Financial Odyssey

Greece’s Financial Odyssey

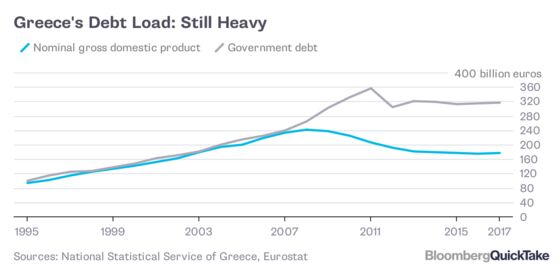

(Bloomberg) -- After eight long years, Greece is about be unshackled from its handcuffs. Well, sort of. Since 2010, the European Union and the International Monetary Fund have committed more than 300 billion euros ($352 billion) in bailout loans to Greece. In return, lenders imposed harsh fiscal terms on the country, which had to meet strict budgetary targets and accept frequent inspections. On paper, the belt-tightening worked, with Greece now running surpluses. But the economic toll has been immense: The economy has shrunk by more than a quarter, a million jobs have disappeared and thousands of Greeks have seen their living standards fall below the poverty line. As Greece prepares to exit the rescue program in August, some economists fear the terms — forbearance on some loan repayments but no debt forgiveness — could invite a new crisis. For now, the biggest questions are whether the country can really stand on its own, and when Greeks will start seeing the economic recovery in their wallets.

The Situation

Alexis Tsipras, the brash young leftist who became prime minister in 2015 on a pledge to end austerity, in the end fulfilled creditors’ conditions to keep bailout funds flowing. He raised taxes, cut government spending, reduced pension payouts and sold state assets to achieve a primary budget surplus (not counting interest on the national debt) of 4.2 percent of output and an overall surplus of 0.8 percent in 2017. Tsipras has even pulled off two bond sales since July 2017. With the economy on course to grow 1.9 percent in 2018, euro-area finance ministers in June added an extra decade to repay about 100 billion euros of debt to ease the country’s road ahead, once the rescue program ends in August. Some people, including Christine Lagarde, head of the IMF, remain skeptical that Greece's long-term future is assured, considering that the ratio of debt to output remains sky high at 179 percent. Unemployment, at 20 percent, is the worst in the EU. And the country's banks remain mired in bad loans, which equal about half their assets. To make sure Greece doesn't backslide, the exit plan requires it to maintain a primary surplus of 3.5 percent of output until 2022, falling to 2.2 percent until 2060. Creditors will also continue to conduct quarterly inspections of the country's reform efforts. While Tsipras hails a new era for Greeks, voters are disenchanted with him. Polls show his Syriza party trailing the center-right New Democracy party in next year's elections.

The Background

Greece built up a mountain of debt over a 30-year period in which conservatives and socialists traded power, competing for votes with spending sprees financed by international debt. All the while, tax evasion flourished and budget shortfalls were swept under the rug. The true size of the profligacy was revealed in 2009 when Greece acknowledged that its deficit was four times what EU rules allowed, later upping that to five times the permitted amount. Three bailouts followed, each accompanied by strict orders to cut spending and raise new tax revenue. Greece in 2012 forced private creditors to write down 100 billion euros from the face value of bonds, for the biggest sovereign debt restructuring in history. By 2015, voters had had enough of austerity, handing an electoral victory to Syriza. In a referendum, voters also resoundingly rejected the creditors’ latest offer and a Greek exit from the euro area seemed likely. But facing the likelihood that rejecting the deal would lead the European Central Bank to withdraw the emergency aid keeping Greek banks afloat, Tsipras gave in. He’s since bowed to the same conditions imposed on his predecessors.

The Argument

The Greek crisis highlighted tensions between national sovereignty and the rights of lender nations within a monetary union. By dictating Greece’s internal affairs, European creditor countries lessened the fallout from their own electorates, which were hostile to the bailouts. But some economists, and most Greeks, think the lenders were so fixated on imposing austerity that they failed to consider how tax increases and spending cuts would crimp economic growth, worsening the debt load they were trying to lighten. Now, with an exit agreement in hand, Tsipras said Greece "is once again becoming a normal country, regaining its political and financial independence." His critics say that's debatable, pointing to the continued oversight by creditors and to what they see as unrealistic primary surplus requirements that could weigh on the economy.

The Reference Shelf

- A Bloomberg QuickTake explains why three bailouts didn’t solve Greece’s debt problems.

- The European Commission's guide to financial assistance to Greece.

- The Bank of Greece summarized its Chronicle of the Great Crisis from 2008 to 2013.

- The Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy has a crisis observatory page.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Paula Dwyer at pdwyer11@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.