Russian Gas

Russian Gas

(Bloomberg) -- Europe’s relations with Russia are at their lowest point in decades. At the same time, the Continent’s buying more Russian natural gas than ever. Europe vowed to free itself from the Russian stranglehold on its energy supply, after gas shipments headed west were twice disrupted. Now a plan to double Russian gas shipments to Germany, the biggest buyer, through a new pipeline is dividing European leaders and becoming a growing worry for the U.S. There are fears the links will enhance Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ability to use natural gas to squeeze critics and reward allies.

The Situation

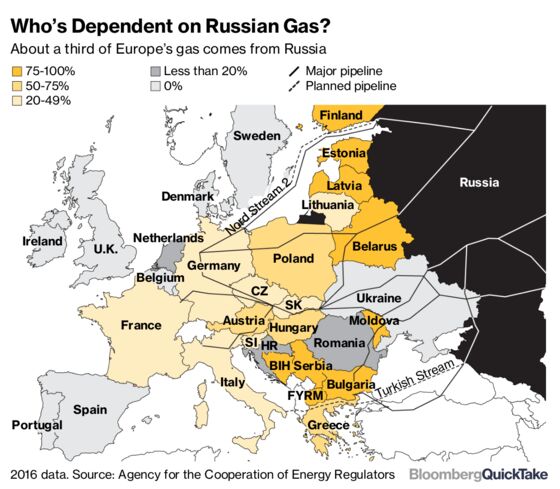

Europe last year purchased record volumes of gas, worth $38 billion, from Russia’s Gazprom PJSC, in part to make up for depleted fields in the U.K. and the Netherlands. Natural gas provides about 22 percent of Europe’s energy mix; about a third of that comes from Russia. Construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline under the Baltic Sea to Germany will begin this year, led by Gazprom and partly financed by European energy companies. A group of 39 U.S. senators wrote to President Donald Trump asking him to block the project, saying it would make American allies “more susceptible to Moscow’s coercion and malign influence.” Poland, Slovakia and other countries that host existing pipelines are also opposed, warning that the plan will tighten Russia’s hold over the region by giving it the capacity to bypass countries at will, including Ukraine. Russia has been locked in conflict with Ukraine since 2014, when a pro-Russian president there was forced from power and Russia seized the country’s Crimean Peninsula. The aggression triggered U.S. and European sanctions against Russia. More recently, the U.K. said it would seek to secure gas from other sources after blaming Russia for the nerve-agent poisoning of a former spy in England in March. The Kremlin has denied involvement.

The Background

With its vast Siberian fields, Russia has the world’s largest reserves of natural gas. It began exporting to Poland in the 1940s and laid pipelines in the 1960s to deliver fuel to captive satellite states of what was then the Soviet Union. Even at the height of the Cold War, deliveries were steady. But since the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia and Ukraine have quarreled repeatedly over the pipelines through Ukrainian territory that carry the bulk of Russia’s Europe-bound gas. In 2006 and 2009, disputes over pricing and siphoning of gas led to cutoffs of Russian supplies. The second shutdown lasted almost two weeks in the dead of winter. Slovakia and some Balkan countries had to ration gas, shut factories and cut power supplies. Since then, the most vulnerable countries have raced to lay pipelines, connect grids and build terminals to import liquefied natural gas, a supercooled form of the fuel that can be shipped from far-away fields, such as those in Qatar. Russia relies on oil and gas to fund more than a third of its government budget.

The Argument

Russia has urged Europe to keep diplomatic disputes and its energy trade separate. So far, it largely has, though German Chancellor Angela Merkel said Nord Stream 2 couldn’t go ahead if Russia uses it to isolate Ukraine and damage its economy. She said the project won’t disrupt the continent’s efforts to diversify its energy sources, since other pipeline expansions will bring more gas from places such as Scandinavia. Forging a unified European position has been hard, partly because dependence on Russian gas varies so widely: Spain doesn’t use any, while it makes up 97 percent of Bulgaria’s supply. Alternative sources of energy for powering Europe’s homes and factories come at a much higher price (LNG) or pollute much more (coal). The issue has been complicated by Germany’s decision to shun nuclear power after reactor meltdowns at Japan’s Fukushima plant in 2011 and from the phaseout of coal in countries from the U.K. to Italy to meet goals for reducing carbon emissions. Europe could produce more of its own gas were it not for widespread opposition to fracking, a technique to tap gas trapped in rock layers that has been blamed for earthquakes and groundwater pollution.

The Reference Shelf

- A Bloomberg analysis of why Russia is set to expand its stranglehold on Europe’s gas market.

- The European Commission explains its Energy Security Strategy.

- An EU stress test of gas supplies in October 2014 showed a six-month disruption in Russian gas would severely hurt eight countries.

- The Gas Infrastructure Europe website provides live monitoring of gas storage levels in the 28 EU countries and Ukraine.

- Oxford Institute for Energy Studies report on reducing European dependence on Russian gas and its study of the 2009 shutoff.

- QuickTakes on Ukraine, fracking, fracking in Europe and liquified natural gas.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Leah Harrison at lharrison@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.