China’s Two-Child Policy

China’s Family Size Limits

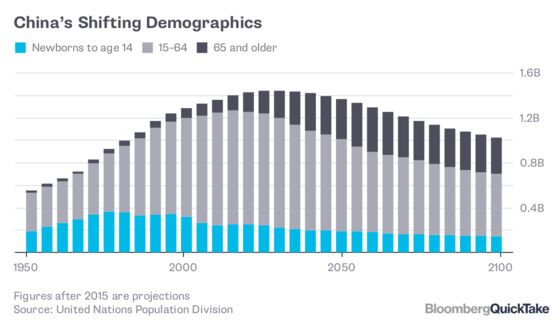

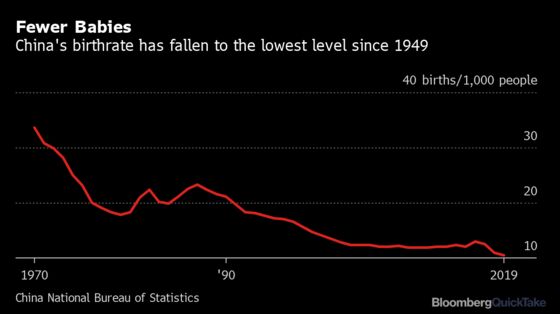

(Bloomberg) -- Please have a second baby. That’s China message for couples after decades of limiting families to just one child. Why the turnabout? China is aging. By 2040, projections show that 24 percent of the population will be 65 or older, a slightly higher rate than in the U.S. and more than twice India’s share. This threatens an economic boom that’s been built on a vast labor supply. And there may not be enough able-bodied people to take care of all those seniors. So in 2016, China changed its rules to allow as many as two children. But many couples weren’t convinced that two were better than one: Births in 2019 fell to the lowest level in almost six decades.

The Situation

Policy makers are increasingly concerned that drastic action is needed to face a quickly graying society. China’s parliament struck family-planning policies from the draft of the new Civil Code, slated to be passed in March. Then an official told attendees at a United Nations conference that China wouldn’t set population limits in the future. The nation forecasts its population will peak at 1.45 billion by 2030 — possibly as soon as 2027. China’s working-age population — those aged 16 to 59 — declined by 890,000 in 2019, a trend that may be chipping into gains in productivity. The lifting of the one-child rule worked at first. The number of newborns in 2016 was 17.9 million, a jump of more than 1 million from the year before. However, births dropped each year after that, to 14.6 million in 2019, the lowest since 1961. The average number of births per woman over a lifetime, at 1.7, was still below the 2.1 needed for a steady population, excluding migration.

The Background

After the creation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the government trained tens of thousands of “barefoot doctors” to bring health care to poor and rural areas. The mortality rate plummeted and the population growth rate rose from 16 per thousand in 1949 to 25 per thousand just five years later. This prompted the first attempts to encourage family planning in 1953. Still, total population expanded to over 800 million in the late 1960s. By the 1970s, China was facing food and housing shortages. In 1979, its leader, Deng Xiaoping, decided to limit most couples to just one child. (There were exceptions for rural farmers and certain situations, like when a first child was handicapped.) It worked: The annual population growth rate averaged just 0.6 percent. But to enforce the rules, Human Rights Watch says, China forced women to have abortions. Children born outside the state plan weren’t allowed to have their hukou — a government registration needed to access some benefits. The one-child years left social scars. The traditional preference among Chinese parents for sons caused many parents to abort female fetuses, and the male-to-female ratio reached 120-to-100 in some provinces. The imbalance empowered single women to reject men without money, leaving a generation of single men called “bare branches” because they can’t add to their family trees. The sex ratio for births has been dropping in recent years, though the 2019 estimate, 113 boys for every 100 girls, was still above the natural rate of 105 to 100.

The Argument

It could be difficult to persuade Chinese couples to have more children. Time and financial concerns mean that many feel they can only afford to have one child. For working women, many “view multiple childbirths and successful career as fundamentally incompatible,” according to a study by Yun Zhou at Brown University. A commission created by the U.S. Congress found they face “severe discrimination” from employers, especially surrounding pregnancy and maternity benefits. While scrapping the cap altogether to allow more than two children could drive faster fertility improvements, officials might need to build up medical services and schools and work out new tax breaks for families first. Immigration isn’t likely to be an answer, as China has strict limits on foreign workers. Businesses aren’t waiting for the reinforcements. Labor shortages have pushed manufacturers in the Pearl River Delta, China’s export powerhouse across the border from Hong Kong, to invest in automation and robots.

The Reference Shelf

- National Geographic shows how the one-child policy changed China in charts.

- Bloomberg News explained China’s widening pension gap.

- China specialist Yuwen Wu examines the birth rate crisis for the BBC.

- The New York Times talked to working mothers in China about the discrimination they face.

- China is not alone: QuickTakes on lower fertility rates worldwide and how Japan is handling its shrinking population.

--With assistance from Dandan Li.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Grant Clark at gclark@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg