How Conoco's Fight With Venezuela Landed in Curacao: QuickTake

How Conoco's Fight With Venezuela Landed in Curacao: QuickTake

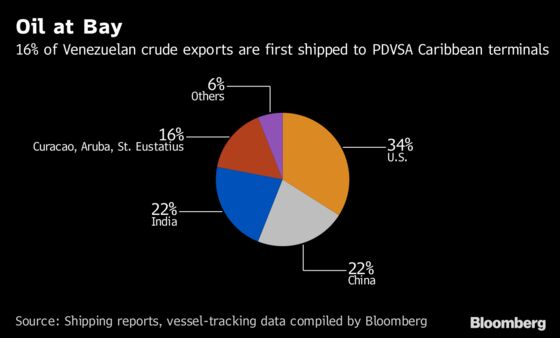

(Bloomberg) -- ConocoPhillips is going all out to recover $2 billion it was awarded in arbitration from Venezuela. First it froze the assets of Venezuela’s state-run oil giant, Petroleos de Venezuela SA, at Caribbean harbors that serve as key waystations for much of Venezuela’s crude exports. Now it’s pushing to do the same in the U.S., Europe and Asia. The fight pits the world’s biggest independent explorer against the holder of the world’s most significant crude reserves, and it’s exploring some surprising legal territory.

1. Why does Venezuela owe $2 billion?

In 2007, under then-President Hugo Chavez, Venezuela moved to strip four of the world’s biggest oil companies, including Conoco, of control over several billion-dollar crude projects in a region of the country known as the Orinoco Belt, named for the river that flows over the world’s largest deposits of petroleum. Chavez’s argument was that the projects played a strategic role in the country’s development and sovereignty. His government seized two Orinoco ventures and one smaller project. That’s when Conoco began its push for reimbursement.

2. Where did Conoco turn first?

Believe it or not, the chamber of commerce. Not the local one, mind you, but the International Chamber of Commerce, a private organization headquartered in Paris and used by member states and companies since 1923 as an arbiter of last resort for international financial disputes. In Conoco’s case, the ICC ruled the company should be paid $2.04 billion for the assets it lost. The problem: The ICC doesn’t have the ability to enforce its rulings. That’s up to local jurisdictions.

3. So Conoco had to go back to Venezuela?

No. Instead, it filed legal actions on the Caribbean islands of Curacao, Aruba, Bonaire and St. Eustatius, where ships regularly offload Venezuelan crude to tankers and refineries, part of its journey to China, Russia, and even the U.S. All four of those islands are former Dutch colonies, and still follow the Netherlands legal system, which happens to be friendly to asset-seizure requests. On May 4, a court in Curacao took less than an hour to allow Conoco to freeze $636 million worth of assets and accounts held on the island by PDVSA. Courts in the other islands did the same.

4. What exactly is frozen, and what does that mean?

Courts in the Caribbean islands have frozen PDVSA oil and oil products sitting in storage tanks in all the islands and in oil tankers. Frozen means they can’t be touched by either party until final legal arguments are made and a ruling is issued. Conoco also is trying to take over a terminal in Bonaire owned by PDVSA, and money transfers to PDVSA.

5. How have the Venezuelans responded?

PDVSA hasn’t commented officially, although a person familiar with the company told Bloomberg that it intends to pay off the arbitration award. PDVSA has faced criticism for not moving aggressively to take precautions commonly used by distressed debtors to protect assets from seizure, including so-called “free-on-board" contracts that designate cargo no longer belongs to a company once it leaves local shores.

6. What has Conoco seized so far?

Nothing yet, since the court ruling is not yet final. But the litigation puts any other company or organization that works with PDVSA in its own legal jeopardy, effectively freezing the assets in place.

7. What happens next?

The Caribbean rulings were “ex parte" decisions, orders based on arguments from only one side of a legal dispute. They still must survive a more detailed legal review. PDVSA, meanwhile, is seeking a license from Venezuela’s environmental agency to carry out ship-to-ship transfers off the coast of Venezuela, rather than in the Caribbean, according to people with knowledge of the situation. Meantime, Conoco is looking to expand pressures on its quarry, Chief Executive Ryan Lance said in a May 15 news conference. The U.S. company filed similar requests in New York, London, Paris and Hong Kong in a push to place liens on assets in other parts of the world.

8. Who gets hurt by all this?

Beyond the direct impact on the regime of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, which is bankrolled by the export of crude oil, any hindrance of PDVSA’s business could mean that refineries from the U.S. to Asia find themselves out of the Venezuelan oil many of them were set up to run. That could mean higher oil prices and more pain at the pumps. And pity the poor folks in the Caribbean, where the oil facilities are a major employer, as well as a prime source of fuel for locals. Four of Curacao’s government-controlled companies, including the owner of the Isla refinery, went to court this week seeking to allow delivery of the fuel oil originally targeted for them. On May 18, PDVSA was ordered to supply fuel oil to Bonaire and Curacao starting no later than May 22, with the proceeds to be deposited into in an escrow account until courts decide if PDVSA or Conoco is entitled to the money

9. Who’s going to win?

It’s unclear. PDVSA still has options, including a challenge to the arbitration ruling that could take a year to decide. But Conoco’s progress could “start a chain reaction" of competing claims against PDVSA, according to Francisco Monaldi, an energy policy expect at Rice University in Houston. “You could have an avalanche of new creditors."

The Reference Shelf

- A QuickTake explainer on Venezuela’s collapse.

- A Bloomberg View editorial on Venezuela’s upcoming elections.

- What PDVSA could have done to prepare for Conoco’s legal assault.

--With assistance from Jef Feeley and Edvard Pettersson.

To contact the reporters on this story: Alex Nussbaum in New York at anussbaum1@bloomberg.net;Ezra Fieser in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic at efieser@bloomberg.net;Lucia Kassai in Houston at lkassai@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Reg Gale at rgale5@bloomberg.net, Laurence Arnold

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.