With Treasuries Finally at 3%, Here's What Comes Next: QuickTake

The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield, has finally reached 3 percent, a level it hadn’t topped in more than four years.

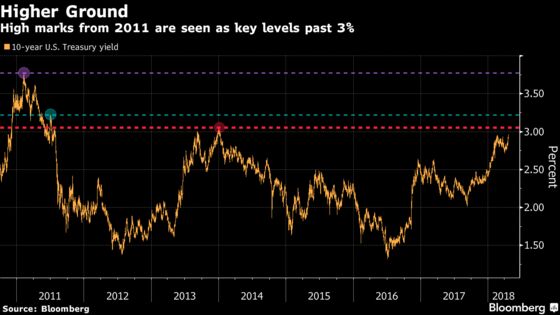

(Bloomberg) -- The global bond market’s primary benchmark, the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield, has finally reached 3 percent, a level it hadn’t topped in more than four years. That’s more than just a nice round number. Higher yields make the burden of everything from mortgages to student loans and car payments even heavier. Some market gurus see it as a turning point with effects that could be felt for years -- and not just in bonds. With the Federal Reserve signaling interest rates are going up even more, investors in riskier assets like stocks and high-yield debt are left to wonder if this is how their post-recession party ends.

1. Why is 3 percent a milestone?

Since 2011, had been touched only twice, briefly, in 2013 and early 2014, before a bond bull market drove yields to record lows. Prominent fixed-income investors like Jeffrey Gundlach at DoubleLine Capital and Scott Minerd at Guggenheim Partners have cited the 3 percent threshold as critical to determining whether the three-decade bull market in bonds is at an end. In the minds of analysts who look at market patterns, once the yield breaks much beyond the 3.05 percent, to levels last reached in 2011, that threshold could flip to a floor from a ceiling.

2. Why does it matter?

The 10-year Treasury yield is a global benchmark for borrowing costs. Corporations will have to pay more to issue debt, which they’ve done cheaply in recent years. So will state and local governments, which could jeopardize investments in public infrastructure. Homeowners will face higher mortgage rates (or lose out on refinancing at a lower cost). Taking out loans for cars or college could also become more expensive.

3. What happens next?

The general consensus is that yields have moved quite far already. More than half of the 56 analysts surveyed by Bloomberg expect the 10-year yield to end 2018 within 25 basis points of 3 percent, meaning a range-bound remainder of the year. Bond bears counting on even higher yields would argue that inflation is just around the corner and the economy is about to get even hotter. Bond bulls would say the Fed is getting close to its limit for rate hikes because the economy can’t withstand much steeper borrowing costs without slowing down.

4. What’s so important about yield?

A bond’s yield is a measure of the return an investor can expect from buying it. It’s determined by the bond’s interest rate and the price paid for it. For instance, buying a security that pays a fixed 2 percent (the “coupon”) at face value (known as “par”) results in a yield of 2 percent. Buying it at a cheaper price would raise the yield for the investor, while paying a premium would reduce the overall yield. (Maybe the most confusing aspect of the bond market to outsiders is the inverse relationship between price and yield.)

5. How do you determine the benchmark 10-year yield?

In the $14.9 trillion Treasuries market, the benchmark is based on the most recently auctioned 10-year security (known as the “on-the-run”). It’s the best measure because it tends to have a price close to par and a coupon close to the current yield.

6. Why are yields going up?

The Fed is raising its short-term lending rate as the U.S. economy strengthens, after holding it near-zero in the wake of the financial crisis. The three rate hikes last year pushed up two- and five-year Treasury yields in particular, but they’ve also affected 10-year yields as central bankers expect more increases this year. Another reason: inflation is showing signs of picking up, which erodes the value of bonds’ fixed payments and leads investors to demand higher yields.

7. Will my fixed-income mutual fund take a hit?

Yes. The value of a fixed-income fund’s shares are determined by the price of the bonds it holds -- and as yields rise those prices will fall. The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, the benchmark for a wide swath of mutual funds, fell 1.15 percent in January and another 0.95 percent in February. The silver lining of a selloff, however, is that fund managers are able to buy new bonds at higher yields, offering juicier fixed payments down the road. With 10-year Treasuries offering 8 or 9 percent yields in the early 1990s, it’s no surprise that the index has rarely had a down month.

8. How will this affect stocks?

Market watchers partly blamed the rapid rise in Treasury yields for the equity market correction at the start of February, which resulted in the largest daily point drop ever in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Stocks wobbled again in March, but have mostly stabilized. In theory, higher corporate borrowing costs would erode a key element of companies’ profitability. But they’re also getting a windfall from the Republican tax plan. The area to watch is high-dividend stocks, which have served as bond proxies for years since they offered high fixed payments. Now that Treasury yields have caught up, investors are starting to sell equities.

The Reference Shelf

- A trading guide for when the 10-year U.S. yield hits 3 percent.

- A Businessweek story on what a bond bear market would look like.

- The Treasury Department’s daily yield curve rates.

- QuickTake explainer on negative interest rates.

To contact the reporter on this story: Brian Chappatta in New York at bchappatta1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, John O'Neil

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.