Even for Bezos, Fixing Health Care Will Be Hard

Even for Bezos, Fixing Health Care Will Be Hard: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) -- Over the last few decades, a series of grand efforts to control U.S. health care costs have been loudly announced, and have mostly flopped. Health care now accounts for about 17 percent of gross domestic product, nearly twice the average in other developed countries. Warren Buffett has compared the system to a hungry tapeworm eating away at its corporate and taxpayer hosts. Buffett is trying to do something about it as part of the health-care alliance formed in January between his Berkshire Hathaway Inc., Jeff Bezos’s Amazon.com Inc. and Jamie Dimon’s JPMorgan Chase & Co. Now the three have appointed surgeon-writer Atul Gawande to lead the venture. A week later Amazon bought the online pharmacy PillPack Inc. Whether it succeeds or not, the joint venture is likely to be interesting.

1. What will the three-way venture do?

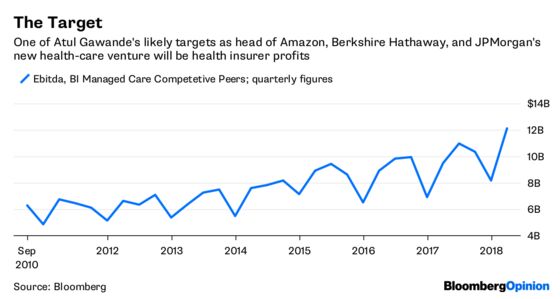

It will initially focus on new technology to simplify health care and reduce costs for the three companies’ 1 million-plus employees. After his appointment, Gawande laid out some initial goals: targeting administrative costs, inflated prices and "misutilization,” which he defined as "the wrong care at the wrong time and the wrong way." Investors in the health-care industry are getting jittery -- both the initial announcement and news of Amazon’s purchase of PillPack yo-yo’d the stocks of health insurers and drug plans.

2. Why wouldn’t it succeed?

The health system has powerful incumbents -- from insurance companies and drug benefit managers to hospitals and doctors -- and every dollar one party saves is a dollar out of somebody else’s pocket. The three companies have little experience in the industry and little in common other than being run by famous billionaires. JPMorgan’s commitment could wane if the project looks like it will damage clients and its bankers begin losing out on future health-care deals. Berkshire Hathaway is a collection of subsidiaries that run independently, which could make it harder to pool their purchasing power. Amazon’s involvement, however, could be key.

3. Why is Amazon’s role so important?

Amazon has wreaked havoc on everything from books to electronics to household staples and could apply what it has learned to health care. With the company’s purchase of PillPack, expected to close in the second half of 2018, Bezos might be able to push drug prices down eventually. But health care pricing is fiendishly complex. Markets for services are local, so a contract with doctors and hospitals in Amazon’s Seattle hometown won’t help JPMorgan’s bankers in New York. And really cutting costs could mean saying no to expensive drugs and services -- and risk annoying employees in a tight labor market who have come to expect generous benefits.

4. Why do some see great promise?

In theory, the new venture will have the funding, influence and chutzpah to try new, disruptive approaches, such as bargaining directly with drugmakers or creating an online bidding system to transparently negotiate drug prices, experts said. If the three companies pool all their employees, they’ll have more leverage to negotiate lower rates for doctor visits, hospital stays and other health services. They could use Amazon’s consumer-technology prowess to help employees become better shoppers for health services, or cut out many of the industry’s middlemen. And Amazon, Berkshire and JPMorgan have assigned some of their top managers to oversee the alliance.

5. Why Gawande?

In some ways, he’s a very likely and highly unlikely choice. Gawande practices general and endocrine surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, teaches at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Medical School and is a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine. His writings have detailed the medical cost explosion, and in 2012, he founded Ariadne Labs, a center aimed at improving health care around the world. But Gawande has never run a large-scale organization -- and he has yet to assemble a team around him.

6. Who’s tried this before?

One of the biggest recent efforts began two years ago when a consortium of large employers, including International Business Machines Corp. and American Express Co., launched the Health Transformation Alliance. It negotiated drug contracts with UnitedHealth Group Inc.’s OptumRx and CVS Health Corp., two of the largest pharmacy-benefits managers. The alliance, which now counts 46 companies, says its members are saving a median of 15 percent a year on drug costs, but it hasn’t fundamentally altered the drug-distribution system. Among big companies, Caterpillar Inc. and Walmart Inc. have come the closest to reining in drug middlemen. Caterpillar saved tens of millions a year by creating its own list of covered drugs and negotiating deals with pharmacies on prices. Walmart is experimenting with buying health services for its employees directly from providers.

7. What about other tech giants?

Microsoft Corp. announced in June that it had hired Jim Weinstein and Joshua Mandel, two industry veterans, to lead its restructured health division, now called Microsoft Healthcare. The software company is trying to find safe ways for health-care data to be stored in the cloud, building on its previous research in that area. Other tech giants have dabbled in the health sector as well. Apple Inc. made its health records app’s API available for outside developpers in June, banking on a spur in app development built on its service. Alphabet Inc.’s Google Health, however, was discontinued in 2011.

8. Wasn’t Obamacare supposed to control costs?

In theory, yes. Obamacare was supposed to help individuals move off of expensive company plans and shop for their own coverage -- at prices they could afford -- on the new health-care exchanges. But that largely hasn’t come to pass. For the most part, the majority of workers continue to get coverage from their employers, and the law has been under constant attack from Republicans who have dismantled key parts of it. Obamacare included a levy on high-cost employer coverage, known as the Cadillac Tax. The tax was designed to push employers to rein in the cost of their health benefits, but it’s been repeatedly delayed by lawmakers.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTake explainers on the individual mandate in Obamacare, the Donald Trump administration’s changes to Obamacare, what “Medicare for all” means, why insurers are quitting Obamacare and the debate over U.S. drug prices.

- A Congressional Budget Office report on where people get health coverage.

- The Kaiser Family Foundation’s annual report on employer-provided health insurance.

- The Milliman Medical Index shows the climbing cost of health care.

- The website of the Health Transformation Alliance.

To contact the reporters on this story: Robert Langreth in New York at rlangreth@bloomberg.net;Zachary Tracer in New York at ztracer1@bloomberg.net;Aziza Kasumov in New York at akasumov@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Drew Armstrong at darmstrong17@bloomberg.net, Cecile Daurat, Paula Dwyer

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.