Monthly U.S. Jobs Report

Monthly U.S. Jobs Report

(Bloomberg) -- The first Friday of most months brings a new chapter in the U.S. government’s running chronicle of economic health: The monthly jobs report. It’s a list of numbers that calls forth so many widely varying responses that it can seem like a nerd’s Rorschach test. Stock and bond markets gyrate in response to it. Central bankers parse it for policymaking guidance. In many months, different parts of the data seem to support contradictory points of view. President Donald Trump, who once questioned whether its numbers are accurate, has taken to tweeting positively about them. To understand the statistics it helps to know why and how each number is compiled. But even then it may be useful to keep more than a few grains of salt handy when you hear huge conclusions being drawn.

The Situation

The number of people filing for unemployment benefits has declined to the lowest level in more than four decades. Private employers have added jobs for nearly eight years. The share of people working part-time rather than full-time for economic reasons has fallen. Even the participation rate, the measure of those working or looking for jobs, has been stable after falling to lows not seen since the 1970s. Wages, long dormant, are finally heading up, though slowly.

The Background

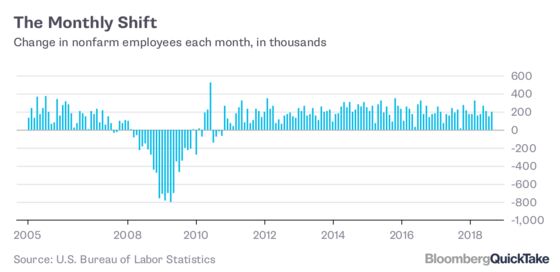

Two data points get the most attention when the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases its monthly report on the employment situation: the unemployment rate and the number of jobs added or lost. The BLS calculates unemployment rates by surveying people over the age of 16 who aren’t in the military, in prison or in mental hospitals. They are asked whether they are currently working and, if not, whether they have searched for a job in the last four weeks. Those who have stopped looking for work — whether because they have retired or because they have given up hope of finding a job — are considered outside the labor force. The data come from the Current Population Survey, which polls about 60,000 households every month. In addition to the unemployment rate, the CPS, which is commonly known as the household survey, is also the source of data on how many people are working part-time vs. full-time, as well as information on the age, gender, and racial composition of the labor force. Even though the household survey counts how many people are working, the headlines about the number of jobs gained or lost each month come from the Current Employment Statistics program, which surveys about 145,000 business establishments and government agencies. It also uses models to estimate how many new businesses are born and how many shut down each month. Known to most as the establishment survey, the CES produces data on the number of people working in each industry, how much they are paid, and how many hours they work. The details of the household survey are helpful for understanding the changing nature of the workforce in terms of age, gender, race, and education; the details of the establishment survey reveal which industries are growing and shrinking.

The Argument

Many analysts think the focus on monthly changes is misleading. The total number of people working changes by only about 0.15 percent each month, while the initial estimates of monthly changes are regularly revised by about 50 percent in either direction. The seasonal adjustment algorithm can introduce even more errors. U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has said “excessive influence” is placed on the headline unemployment index to inform policy decisions. He said a fuller unemployment measure should include “discouraged workers” who have stopped looking because they thought there were no openings. Analysts disagree on how many jobs the economy needs to create in order to reach and then maintain full employment. Their estimates depend on assumptions about population growth, aging and immigration. These disagreements have real-world consequences since they affect whether Fed policy makers decide to ease or tighten up financial conditions.

The Reference Shelf

- Bureau of Labor Statistics guide on frequently asked questions about measuring unemployment and its “Handbook of Methods.”

- Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Jobs Calculator and Spider Chart.

- New York Times article on how the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics keeps politics out of its data.

- A Bloomberg graphic on who’s hiring and a QuickTake on full employment.

A graphic in an earlier version of this article rendered the unemployment rate incorrectly.

Matthew Klein contributed to the original version of this article.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Anne Cronin at acronin14@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.