South Korea’s Chaebol

South Korea's Chaebol

(Bloomberg) -- The story of South Korea’s transformation from economic minnow to one of the world’s largest exporters owes much to its sprawling, family-run conglomerates. Known as chaebol, these long-time pillars of the nation’s “miracle economy” include the likes of LG, Hyundai, SK, Lotte and — largest of them all — Samsung. Yet the chaebol’s oversized influence and cozy relationship with government, highlighted by an influence-peddling scandal that cost the country’s president and Samsung’s top executive their jobs, have cast an intense spotlight on the web-like conglomerates as many have been struggling with generational transitions. Is it finally time for change at the chaebol?

The Situation

2017 was supposed to be a watershed year for chaebol after Samsung’s top executive was jailed as part of the scandal that toppled Park Geun-hye, South Korea’s president. Jay Y. Lee, the de facto head of Samsung Group, was sentenced to five years after a court convicted him of bribing his way to greater control of the Samsung empire his family founded. But Lee appealed the conviction and in early 2018 the Seoul High Court freed him after reducing and suspending the sentence, sparking public anger. (South Korea’s highest court in August 2019 ordered retrials for Lee and Park.) In the past, business leaders, including Lee’s father, were convicted for corrupt behavior only to be let off. Lee — who went back to Samsung Electronics as co-vice chairman after his release — was accused of playing a role in payments of tens of millions of dollars that Samsung made to benefit a close friend of deposed president Park. The Lotte retail group’s chairman was convicted in 2018 in another trial relating to Park and handed a 30-month jail term. Eight months later, an appeals court freed him. Public discontent with chaebol has been brewing. At a hearing in 2016, nine chaebol leaders seated together faced a barrage of questions from lawmakers, as hundreds of thousands of protesters calling for the president’s ouster vented their anger at the conglomerates. Park was found guilty in 2018 of crimes ranging from bribery to coercion, abuse of power and the leaking of state secrets and sentenced to 24 years in prison, where she remains.

The Background

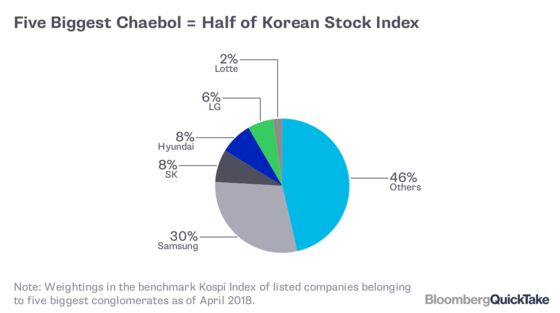

The chaebol, which means “wealth clique” in Korean, are widely believed to have been influenced by Japan’s zaibatsu — both share the same Chinese characters and meaning. Like the chaebol, zaibatsu were family controlled conglomerates that dominated Japan’s economy until they were disbanded by the U.S. after World War II. In South Korea, establishing chaebols was viewed as a way to fast-track the country’s economic development. Shortly after taking over the government in a military coup in 1963, Park Chung-hee, the father of the deposed president, launched a modernization effort driven by “guided capitalism,” in which government-selected companies undertook major projects often financed with government-backed loans. There are now 45 conglomerates that fit the traditional definition of a chaebol, according to Korea’s Fair Trade Commission. The top 10 own more than 27% of all business assets in South Korea.

The Argument

While the chaebol helped make South Korea an economic success story, many politicians and investors argue that the system is a cultural relic poorly suited to the 21st-century economy. The shares of chaebol-linked companies trade at lower multiples of earnings than their peers in the U.S., Europe or Japan (a phenomenon called the Korea discount) because of concern over cronyism and cross-ownership. Ordinary South Koreans are also increasingly questioning the consolidation of wealth among a handful of families and the stifling effect they’ve had on small businesses and startups. People are no longer as prepared to turn a blind eye to illegal and improper relationships between government and business as they were in the past, when the chaebol were seen driving growth and creating jobs, according to Kim Sang-jo, chairman of the Fair Trade Commission and a former economics professor at Hansung University. Amid the public criticism, regulators and investors have been pushing to unravel cross-shareholdings and revamp governance structure of the chaebol.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg Businessweek reports on a death watch at Samsung, and how South Korea tried to rein in the chaebol.

- Bloomberg News: The backlash against billionaires after the fall of South Korea’s richest city.

- A QuickTake explainer on the bribery allegations Samsung faced.

- Harvard Business Review looked at how conglomerates differ in developed and emerging markets.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Grant Clark at gclark@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.