Dual-Class Shares

Dual-Class Shares

(Bloomberg) -- It’s an investing principle: One share means one vote, right? Actually, not always. For companies including Ford Motor Co. and Google parent Alphabet Inc., the stock is split into different categories, known as dual-class shares, to give owners of one class greater voting rights than owners of the other. Crucially, that allows minority shareholders — typically a company’s founders or leaders — to retain control of a business. Investors have been grumbling about the undemocratic nature of it all for years, while still buying the shares. Stock exchanges, along with regulators, decide on the ground rules, and some bourses that forbid multiple-class shares are rethinking their position as competition intensifies. In particular, they covet listings by the huge technology firms that increasingly opt for such structures. The compilers of equity indexes, which often include the dual-class shares in their lists, are leading a backlash.

The Situation

Photo-sharing app Snap Inc. took the notion to its extreme by handing zero voting rights to investors in its $3.4 billion initial public offering in 2017. Music streaming service Spotify skipped an IPO altogether and allowed its owners to maintain control after its share listing the following year. Facebook Inc.’s dual-class model gives company founder Mark Zuckerberg less than one percent of the social-media giant’s publicly traded stock and 60 percent of its voting power. But resistance is also taking shape. In 2017, Facebook scrapped a plan to create a new class of shares following legal action by shareholders. And earlier that year, the U.S.-based Council of Institutional Investors, whose members include public pension funds, called for multiple-class listings to be removed from equity indexes. Several of the biggest index compilers took note: S&P Dow Jones Indices and FTSE Russell decided to exclude some dual-class shares going forward. Snap, for example, is now ineligible for the S&P 500, meaning passive funds — whose investments track that index and are worth trillions of dollars — aren’t obliged to buy its stock. At the same time, exchanges that prohibit or limit dual-class shares are considering loosening restrictions, fearing for their status as financial hubs. Hong Kong's exchange operator, which lost out to New York for Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.’s world record $25 billion listing in 2014, approved dual-class shares last year, opening the way for Xiaomi Corp.’s $5.4 billion IPO. Singapore’s exchange also changed its rules to allow them, while the U.K. regulator has discussed relaxing its regulations.

The Background

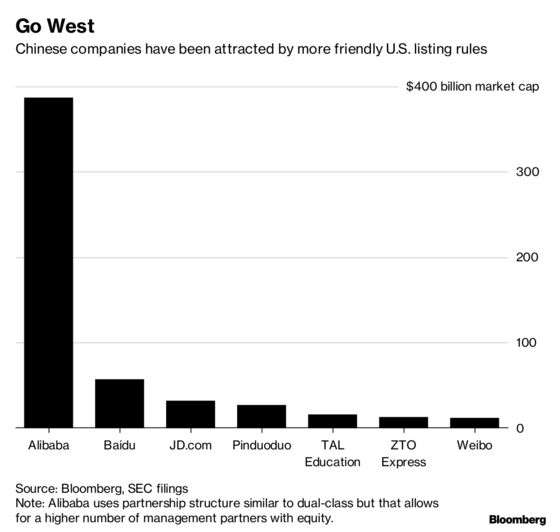

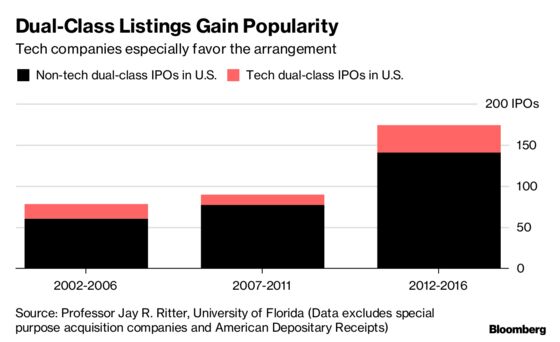

In 1925, Dodge Brothers created a stir on the New York Stock Exchange when it became apparent that the automaker’s owners had total voting control with only 1.7 percent of equity. That eventually led to a 1940 rule limiting multiple-class stock, but that was overturned 46 years later when companies threatened to list on another exchange. While dual-class shares once were used mostly by family-owned firms (Volkswagen AG and Ford) and media companies (The New York Times Co.), the floodgates opened in 2004 with Google’s dual-class IPO. LinkedIn, Groupon, Zynga, Facebook and Fitbit quickly adopted the model, while Google went on to offer shares with zero voting rights in 2014. Multiple-class shares are allowed in many parts of continental Europe, Canada and Brazil. The U.S. has attracted $34 billion of such listings by Chinese firms alone in the past decade.

The Argument

According to detractors, dual-class shares challenge the bedrock notion that those who provide the capital should get a say in how the company is run, by conceding that some investors matter more than others. Supporters say such shares enable executives to focus on the long term and resist expectations by major investors that each quarter’s earnings will be better than the previous one’s. They argue that it’s a mistake to keep firms with dual-class listings out of indexes because it may discourage tech entrepreneurs from taking their businesses public, depriving investors of access to some of the most innovative companies. And they contend it's not the role of index compilers to regulate dual-class shares. There’s no clear, consistent proof that the shares of such firms fare better or worse. Despite their resistance, many institutional investors end up buying stakes in these companies, some of which are too big to ignore. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, the world’s biggest, has spoken out against such dual-class structures but is among the largest investors in Facebook and Alphabet.

The Reference Shelf

- Snap’s version of totalitarian capitalism isn’t so bad, Bloomberg View columnist Justin Fox writes.

- FTSE Russell's paper on voting rights and S&P Dow Jones' announcement on multi-class shares.

- UCLA Professor Stephen Bainbridge says the hysteria over dual-class shares is “vastly overblown.”

- Competition between exchanges for dual-class shares leads to a bit of a race to the bottom, Bloomberg View columnist Matt Levine writes.

- An explainer on China's overseas IPOs.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Grant Clark at gclark@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.