South Africa’s Hopes

South Africa

(Bloomberg) -- When the African National Congress (ANC) swept to power under Nelson Mandela in South Africa’s first multiracial elections a quarter century ago, its campaign slogan assured “a better life for all.” That vision, already somewhat faded, was badly tarnished during the nine-year presidency of Jacob Zuma, which was characterized by scandal, corruption and economic stagnation. Cyril Ramaphosa, who succeeded Zuma in February 2018, is cleaning house — but it could take years to undo the damage to Africa’s most industrialized economy.

The Situation

Ramaphosa’s rise to power produced a wave of optimism that governance would improve in South Africa. He immediately cracked down on corruption, sacking some of his predecessor’s most inept ministers, and in late 2018 appointed a new chief prosecutor. Zuma was indicted on multiple charges, including racketeering and money laundering. Ramaphosa vowed to raise $100 billion in new investment over five years, and has managed to lure about a fifth of that so far. He’s still trying to calm investors rattled by the ANC’s moves to change the constitution to allow land expropriation without compensation, which the party says will aid redistribution of wealth to black citizens. Ramaphosa insists there won’t be land grabs, and any policy shift won’t be allowed to harm the economy or agricultural production. Voters will judge his performance in national elections in May 2019. While disillusionment with Zuma eroded the ANC’s popular support for years and cost it control of Johannesburg, the economic hub, and Pretoria, the capital, in municipal votes in 2016, opinion polls show the party should easily retain its majority control of parliament.

The Background

European settlement in South Africa dates from 1652, when the Dutch East India Co. established a supply post in Cape Town; the British occupied it in 1795 to secure the sea route around the southern tip of Africa. Colonialism spread as the Dutch — known as Boers or farmers — migrated to the interior. Discovery of inland gold and diamond deposits spurred the Anglo-Boer Wars, which the British won in 1902. White colonists adopted a constitution in 1910 that disenfranchised black South Africans, whom they viewed primarily as cheap labor. In 1948, the government started implementing a legal system of separation of races known as apartheid, or apartness. It denied black people the vote, stripped them of land and provided only rudimentary education and health-care services. South Africa endured decades of economic sanctions and an armed struggle by the ANC and other groups. Mandela, who’d led calls for the ANC to take up arms, served 27 years in prison before the government freed him in 1990 and later held multiracial elections. Ramaphosa, born in 1952, has played an integral part in South African politics since the early 1980s. He founded the biggest mineworkers’ union and led talks that ended apartheid. After losing the contest to succeed Mandela to Thabo Mbeki, he started his own investment company, which benefited from requirements that white investors partner with black shareholders. He ended up with stakes in businesses ranging from mining to consumer goods. Ramaphosa returned to full-time politics in 2012, when he was elected as the ANC’s deputy leader; Zuma appointed him deputy president in 2014. He became head of the ANC in late 2017.

The Argument

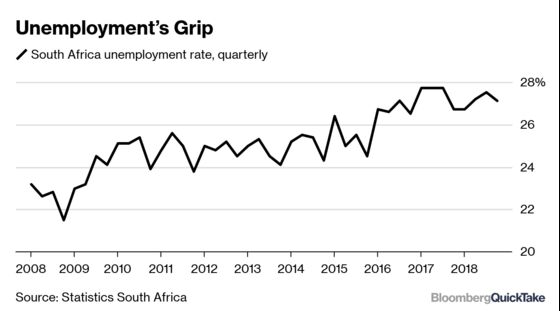

Over the years, South Africa’s government has been able to point to some successes: The size of the economy has almost tripled in dollar terms since 1994, while average life expectancy has risen by 10 years to 64.3 over the past decade. Ramaphosa’s political and business experience raise hopes he can eventually revive the struggling economy and address the plight of an army of poor. South Africa enjoys transport links that are the envy of Africa, a trove of untapped minerals and independent courts. Yet racial inequalities persist, and companies remain largely controlled and managed by whites. The 27 percent unemployment rate will likely stay elevated as a poorly managed public-schools system, ranked among the world’s worst, means more than half of children don’t complete a full 12 years. Chronic power shortages are a constraint on economic growth, and efforts to clean up the state are being frustrated by the scores of Zuma allies who still occupy key posts. But if Ramaphosa succeeds, South Africa could emerge as an example of good governance and democracy for the rest of the continent.

The Reference Shelf

- The ANC’s biography of Ramaphosa and his 2019 state-of-the-nation address.

- World Bank report on inequality in South Africa.

- A New York Times examination of corruption in the nation’s tax agency.

- Bloomberg news on Zuma’s troubled tenure and how Ramaphosa toppled the president.

- Bloomberg QuickTakes on how Zuma was forced out, South Africa’s power shortages and land ownership.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Karl Maier at kmaier2@bloomberg.net, Andy Reinhardt

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.