U.S. Budget Deficit

U.S. Budget Deficit

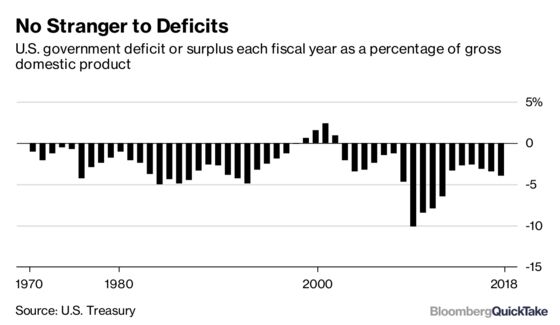

(Bloomberg) -- Remember the budget deficit? U.S. politicians once loudly and frequently decried all the red ink. The complaints faded as the country’s creditors showed no signs that they were worried about the government’s ability to pay its bills and the shortfall melted like ice cream on a summer’s day. The deficit shrank as a share of the economy for six straight years, narrowing to 2.4 percent of gross domestic product in the fiscal year that ended in September 2015. But the gap started widening again, to 3.2 percent of GDP in fiscal 2016 and 3.5 percent in 2017. Congressional Republicans, members of a party once known for fighting against too much government spending, backed tax cuts in late 2017 that have added to the deficit. Get ready to hear a lot about Washington living beyond its means.

The Situation

On Feb. 9, after months of using short-term budget measures to keep the government running, the Republican-controlled Congress passed a two-year budget deal that would raise spending by almost $300 billion. This followed a rewrite of the tax code in December 2017 that’s estimated to reduce federal revenue by almost $1.5 trillion over the coming decade, before accounting for any economic growth that might result. Then the projections included in the 2019 fiscal year budget proposed by President Donald Trump on Feb. 12 broke from a longstanding Republican goal of balancing the budget in 10 years. Not all Republicans are happy with their party’s turnabout on deficits. Members of the House Freedom Caucus, which champions limited government and is against big spending, opposed February’s budget agreement and its additional spending. Some fiscal conservatives are warily watching the bottom line: The U.S. Treasury Department reported that the budget deficit for the 2018 fiscal year rose to a six-year high of $779 billion. That was equivalent to 3.9 percent of GDP in Trump’s first full fiscal year as president.

The Background

Deficit decriers — including President Ronald Reagan — often noted that no business would survive by running its finances in the same way as the government. Yet the historical reality is that the government doesn’t often balance its books. The U.S. has run surpluses in only 12 of the last 77 years. Deficits surged through World War II before peacetime brought three years of surpluses from 1947 to 1949. The ending of the Cold War and the prosperity during the years when Bill Clinton was in the White House led to a $128 billion surplus in fiscal 2001. A year later this turned into a $158 billion deficit following a brief recession and the upheavals of the Sept. 11 terror attacks. The far bigger recession triggered by the global financial meltdown of 2008 meant that President Barack Obama presided over a four-year run of trillion-dollar deficits that ended in 2012. Though the process wasn’t pretty, Obama and the Republican-controlled Congress brought the deficit down from a high of $1.4 trillion in fiscal 2009. Part of the effort was the 2011 Budget Control Act, which mandated $2 trillion in automatic spending reductions from 2012 to 2021. But the automatic cuts, known in Washington as the sequester, were only triggered in 2013; Congress has voted to roll them back in subsequent years. The deficit started climbing again after Congress revived some tax breaks in 2015.

The Argument

Supporters of Modern Monetary Theory say that there’s lots more room for deficit spending on wish-list items like guaranteeing everyone a job, fixing infrastructure and ensuring everyone has access to health care. Their argument isn’t that deficits never matter, but that the U.S. — as the monopoly creator of dollars — isn’t at risk of being forced to default on its debt. But other economists and politicians find the long-term deficit outlook troubling. Leading up to 2024, when the last of the 76 million baby boomers approach retirement age, there will be heavy demands on Social Security and Medicare. Inflation is showing signs of returning, which will swell the government’s annual interest payments. That threat is cited by lawmakers pushing for a smaller government and anti-deficit think tanks like the Peter G. Peterson Foundation and Fix the Debt. And some investors blamed the February 2018 stock market selloff on the fact that Congress is now “willing to spend like crazy.” If anti-deficit forces in Congress aren’t powerful enough to rein in spending, another group could take aim: bond vigilantes. Investors unhappy at the thought of accelerating inflation could sharply cut their purchases of Treasury debt. That’s what happened in 1993, when bond buyers effectively pressured President Clinton to abandon his campaign promise of a tax cut for the middle class.

The Reference Shelf

- Ronald Reagan’s first inaugural address in 1981, decrying deficits.

- The June 2017 Congressional Budget Office outlook of the fiscal situation.

- William Gale, an economist at the Brookings Institution, and Brad DeLong, an economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, debated whether deficits matter.

- A Bloomberg data visualization comparing the House and Senate tax cut plans, and a Bloomberg BNA report on whether the deficit is really a tax problem instead of a spending problem.

- A Bloomberg QuickTake on Modern Monetary Theory.

David J. Lynch contributed to the original version of this article.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Anne Cronin at acronin14@bloomberg.net, Laurence Arnold

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.