Video Is Still a Bit Player in the Art World. Here’s Why

Video Is Still a Bit Player in the Art World. Here’s Why

(Bloomberg) -- In 1974, Barbara London, a young curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, started what was probably the first ongoing video art exhibition program in any museum, anywhere.

Operating out of a former broom closet, she slowly acquired videos by artists including Bruce Nauman, Nam June Paik, and Joan Jonas. The going rate, she says, was $250 per video.

“There was no market at the beginning,” London says in a phone interview. “These early installations cost next to nothing, and yet for a museum, with every acquisition, the money was always tight.”

Today, video art is in every self-respecting contemporary museum collection in the world, and the artists whom London first exhibited are firmly entrenched in the art-historical canon.

Paik, who died in 2006, is the subject of a major retrospective at the Tate Modern that’s up through Feb. 9; Jonas had her own show at the Tate in 2018. Last year, Nauman was the subject of a massive survey that spanned the sixth floor of MoMA along with the entirety of MoMA PS1, while Bill Viola, another founder of the medium, had a retrospective at the Barnes Foundation that ended in September.

“Video art has slowly, radically transformed to encompass a wide range of technical explorations in art,” writes London in her new book, Video Art: The First Fifty Years (Phaidon $35). The medium has moved “from fringe to mainstream.”

And yet for all that, by virtually every measure, video art has yet to match other mediums: In museums, video-heavy exhibitions, while often well-received by critics, fail to generate attendance at the same pace as exhibitions of paintings or drawings or sculpture.

Of the 20 most popular exhibitions of 2018 listed by the Art Newspaper, only two—the Electronic Language International Festival in Rio de Janeiro and Javier Tellez’s Shadow Play at the Guggenheim in Bilbao—could be considered video art. None of the top 10 shows that required paid admission in London or Paris contained video art, according to the same Art Newspaper report. Two of the top 10 in New York—both at the Whitney—did have video, but weren’t specifically devoted to the medium.

The market has been similarly reticent to embrace video art. Nauman, not exclusively a video artist, has arguably been the most successful—his 1987 video No, No, New Museum sold for $1.6 million at Christie’s New York in 2016, while Viola’s most successful lot at auction sold for more than $700,000 at Phillips in London. While these are certainly a large sum to the average American, it’s a drop in the bucket compared with the tens of millions regularly paid for painting and sculpture.

Nor has video art been embraced by the public at large. Nearly everyone in the western world has screens in their home, in the form of TVs or tablets or computers, and yet vanishingly few people use these screens, even occasionally, for video art. (Not all videos need to be on all the time.)

Fifty years in, the question is whether video art will remain a secondary (or tertiary) medium or if it will, in time, come to rival its more static brethren. “The arc is of course fascinating,” says London. “It’s about comfort level. Everyone is comfortable buying a drawing and framing it and putting it on the wall.”

Technical Hurdles

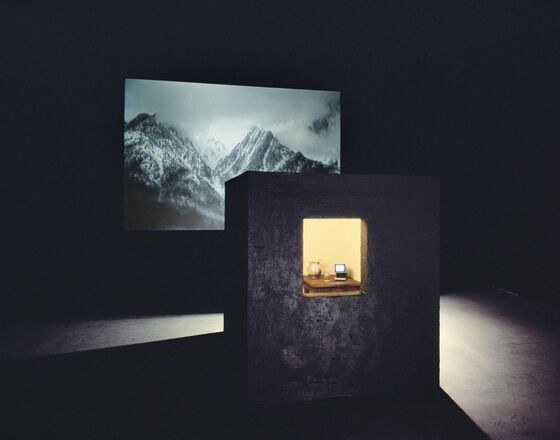

One component that might stand in the way of video art taking its place as an equal of painting is the fact that video, unlike any other medium, requires a machine to actually be realized. You can hang a painting on a wall, but to play a video you need, well, a video player. And video players go obsolete, quickly.

“The art evolved as the tech evolved,” London says. “In the 1960s nobody could touch the equipment except an engineer. The actual film of these videos had to be kept in vaults with stable temperature and humidity levels.” Initially, William Paley, founder of CBS and a MoMA trustee, gave London access to his television engineers, who trained her and two of the museum’s projectionists on how to use a “playback machine.” “We were able to make simple repairs ourselves,” she writes, “and keep the program going.”

Today, even digital video isn’t without its complications, London says. “Even if you’re using off-the-shelf software, you still need technical mavens, who are the new conservators for media art,” she says. “It’s got lots and lots of issues there that makes some people nervous.”

Collector Resistance

Video art has always had collectors, even if they could be counted on one hand. In the mid-1970s, London writes, “Los Angeles-based Stanley and Elyse Grinstein were about the only contemporary art collectors who acquired unlimited-edition videotapes.”

London’s department had high-powered support—the museum’s first video advisory acquisitions committee was founded by Blanchette Rockefeller, the wife of John D. Rockefeller III, and over time various other luminaries came to support the medium. “In the late 1980s and early 1990s, there were people like Peter Norton [the software publisher] who understood software and were acquiring video art,” London says. She recalls visiting Norton’s house and seeing a work by the British artist Gillian Wearing on his computer.

And yet, for all the medium’s adherents, there are many more people who stay away. “Among collectors, there’s a technophobia,” London says. “It’s a big responsibility to acquire these works.”

Attention Spans

The other obvious barrier is the fact that you can’t simply glance at a video and know what it’s about, let alone whether or not it’s any good. If a sculpture is self-evidently bad you can simply walk past it: Video, in contrast, requires a longer time investment, and many people are unwilling to make that kind of commitment.

Initially, London says, video art’s most dedicated viewers were children. “They immediately came and hunkered down and looked,” she says, “because children are very open, and they had television as a reference. So to see a moving image in a museum was, you could say, seductive.”

To London, it didn’t matter if people stayed “a nanosecond or longer,” because even if the interaction occurred for just a split second, “they’d seen something edgy and weird, and the next time they’d come back and say ‘Oh, yeah.’ ” The goal, she says, “was to provide a grounding.”

Nevertheless, London acknowledges that not everyone is that patient. The future, she says, could be shorter and shorter pieces. “The younger generation is glued to its smartphones and is bopping around online,” she says. “So the younger generation of artists is making shorter work. Maybe they’ll make a [break] from the type of art you watch from start to finish.”

Ultimately, London says, “I’m always an optimist. I don’t really follow auction records, but a few of these artists’ works might be moving up there into the price level of paintings and sculpture.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Gaddy at jgaddy@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.