The Macklowe Divorce Art Auction Just Made $676 Million

The Macklowe Divorce Art Auction Just Made $676 Million

(Bloomberg) -- On Monday night, the most anticipated auction of the last three years came to a head.

Thirty five artworks belonging to the real estate developer Harry Macklowe and his ex-wife Linda, carrying a presale estimate of a staggering $439.4 million to $618.9 million, were finally sold at Sotheby’s in New York.

“It’s our largest single-owner sale, ever,” says Charles Stewart, Sotheby’s CEO. “And we only sold half the collection by number of lots tonight.”

The works are the first batch of two to be sold from a collection assembled by the couple over nearly six decades, and dispersed under the orders of a judge: during their acrimonious 2018 divorce, Harry’s side argued the collection was worth $788 million, while Linda’s posited that it was worth $625 million.

The judge, Laura Drager, ruled that the works’ true value should be decided by the market. The first sale was set for Monday night; the second is scheduled for the spring.

After the first sale, which totaled $676 million, it’s beginning to look like even Harry’s high estimate was conservative.

“We set some records here,” Macklowe says, speaking after the sale in a dark blazer, gray slacks, black tasseled loafers, and a giant, colorful scarf. “I’m very pleased.”

High Stakes

Sotheby’s, which vied with rival auction houses for the privilege of hosting the sale, had to guarantee the collection (effectively, commit in advance to it selling for a minimum amount) for a sum rumored to be well above $600 million, meaning the stakes were just as high for the auction house— if not much higher—than for the Macklowes themselves.

“It was our largest guarantee ever,” Stewart says. “We stepped up, we made a bet, and it’s paying off.”

Unsurprisingly then, Sotheby’s pulled out all the stops to ensure the sale would be a success.

In advance of the auction, Sotheby’s toured the art to collectors in Hong Kong, Taipei, Shanghai, Tokyo, Los Angeles, London, Paris, and New York. And on the night itself, Sotheby’s headquarters on York Avenue boasted a massive banner advertising the sale.

Inside, waiters passed around finger food that included tuna tartare and tomato and mozzarella skewers, while a crowd consisting mostly of dealers and industry insiders sipped champagne before slowly making their way to their seats in Sotheby’s cavernous auction room.

A Tense Opening

Normally, evening sales are convivial affairs.

Most of the audience is invariably composed of dealers and art advisors bidding on behalf of their wealthy clients, and even if the lots are worth tens of millions of dollars, there’s an informal, collegial air to the proceedings; people chit-chat with their neighbors even as auctioneers take bids, and people occasionally get up in the middle of a sale to take telephone calls.

Not so on the outset of Monday night, where an unusual tension reigned for the first half of the auction: this would be the biggest single test of the blue-chip art market in years. Chalk it up to the price of the works on offer: not one, but two lots had high estimates of $90 million.

Big Numbers

The sale began slowly, as two comparatively cheap lots, a Baccarat Crystal set by Jeff Koons sold for just under $2 million, above its high estimate of $1.2 million, and a small painting by Robert Ryman (high estimate: $2.5 million, final price: $4.9 million) warmed up the room.

Next it was a de Kooning, painted in 1977, which sold for $24.4 million, well over its high estimate of $18 million, and a white, black, and red painting by Brice Marden which slid over its low estimate of $15 million to sell, with premium, for $17 million.

And then it was time for the first major lot, an 18 foot-wide painting made by Cy Twombly in 2007, which carried an estimate of $40 million to $60 million.

Bidding began at a glacial pace, with bids climbing, after drawn-out intervals, in $1 million increments. “Give me a sign of life,” said the auctioneer, Oliver Barker to the phone bank of specialists for the first but not the last time that evening. The painting finally hammered at $51 million; auction fees brought its final price to $58.9 million.

And that seemed to set the tone for the rest of the major works: solid results, within estimates, which nevertheless represented the very pinnacle of art market.

A painting by Mark Rothko, No. 7 from 1951, sold for $82.5 million after eight minutes of bidding; the result was without fireworks—it was within its estimate of $70 million to $90 million—and yet it was also the second most expensive work by Rothko to sell at auction.

The night’s other top lot, a sculpture by Alberto Giacometti that was conceived in 1949 and cast in 1965, also had an estimate of $70 million to $90 million, and also had a total that fell squarely in the middle: it sold for $78.4 million.

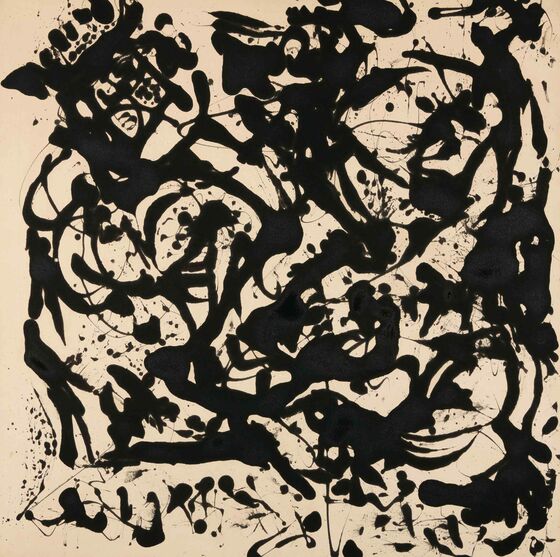

There were a few runaway hits, including a monochrome painting by Jackson Pollock, Number 17 from 1951. It carried a high estimate of $35 million, but a flurry of sustained bids pushed its total, with premium, to $61.2 million, a record for the artist at auction.

Another record was set for an exquisite acrylic and pencil work by Agnes Martin. Two phone bidders pushed the work far past its high estimate of $8 million, until it hammered for just over $15 million; with premium, its total came to $17.7 million.

Ambitious Estimates

The absence of sustained drama at the sale can be partly explained by many of the artworks’ ambitious estimates.

Given that Sotheby's had initially guaranteed the entire sale with an aggressive number to win the collection from rival auction houses, (it then offset its risk by bringing in outside financing for 22 of the 35 lots, in a phenomenon known as third-party guarantees), the works had already been purchased, effectively, for retail prices, says Philip Hoffman, founder and CEO of the Fine Art Group, an art advisory and investment firm.

“There’s a disadvantage sometimes about those big guarantees, because it puts people off,” he says. “Whereas when you have a low starting point, quite often things race away.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.