The Case for Blended Scotch Whisky

Next time you’re at the liquor store looking for a whisky, try out a blend for, you may never stand for a single malt again.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s been a long time since blended Scotch was cool. In 2008, Scotland exported roughly 840 million bottles of it; in 2017 the number was basically the same, even as single malt exports exploded over the same period, from 71.8 million bottles to 122 million bottles, according to the Scotch Whisky Association.

That’s a shame. Because while there’s obviously no lack of bland, cheap blended Scotch, there are also some astounding bottles, whiskies that stand up to the best single malts. It’s time connoisseurs take note.

A “single malt” is a whisky made with malted barley in a pot still at a single distillery: Think Laphroaig, the Balvenie, the Macallan. They’re considered the purest expression of a distillery’s prowess and character. A “blended whisky” is a combination of single malts, often cut with “grain whisky.” Usually made from corn in an industrial-style column still, grain whisky is often lighter and younger than a single malt and gives blends their smoother texture. It also makes them cheaper and, according to your bombastic, whisky-drinking friends, pure swill.

In the mid-19th century, that wasn’t the case; single malt whisky was considered too potent for most Brits, who were used to knocking back port, rum, and claret, aka Bordeaux. Scotch only took off when some enterprising Scots had the bright idea to mix those thick, fiery malts with mild, low-alcohol grain whisky. The blend was born, and so were vast fortunes: the Dewars, the Ballantines, the Chivas brothers, and, of course, the Walkers.

But money doesn’t equal respect. In 1920 bon vivant George Saintsbury wrote in his classic Notes on a Cellar-Book: “I have never cared, and do not to this day care, much for the advertised blends, which, for this or that reason the public likes, or thinks it likes.” Decades later, R.J.S. McDowall called them “an industrial spirit, made out of molasses or sawdust” in his seminal The Whiskies of Scotland.

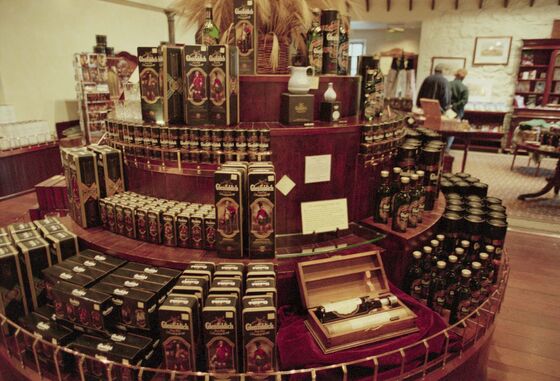

Still, until the 1960s, most whisky was produced exclusively to be blended. For all but the most determined, single malts weren’t an option—they simply weren’t retailed. Yet as whisky geekery grew, Glenfiddich, now one of the world’s best-selling single malts, saw an opportunity. An early ad claimed, “Sit for a Glenfiddich—you may never stand for a blend again.” Consumers, drawn by the cachet and the appeal of bolder flavors, agreed, and blended Scotch began to lose its luster.

Today that trend is starting to reverse as discerning drinkers discover high-quality, small-batch blends. While overall exports of blended Scotch held steady over the last decade, their value grew from £2.4 billion ($3.2 billion) in 2008 to £3 billion in 2017, a sign that global consumers are shifting to more expensive options. In just the past year, U.S. demand for so-called superpremium blends rose 11.8 percent, according to the Distilled Spirits Council.

This bump is a reaction to excellence. Blending, done right, is one of the world’s great arts. Like a chef, a world-class blender first conceives of a complex flavor profile, then draws on dozens of single malts and grain whiskies, in exacting proportions, to achieve it.

That’s what happens at Compass Box, a London-based blending house founded by American expat John Glaser. With names including the Peat Monster and the Spice Tree, Glaser’s whiskies flip conventional wisdom on its head. Instead of mixing malts to reach a bland median, he uses the art of blending to push the limits of the category. Best of all, Compass Box makes whiskies at every price point, from the $39 Great King Street Glasgow blend to the $261 cheekily named “This is not a luxury Whisky,” a blend of grain whisky and single malts from Caol Ila and Glen Ord.

Edinburgh’s Wemyss Malts likewise creates intensely flavored blends with names such as the Spice King, heavy with peat, and the Hive, redolent of honey and flowers. The Lost Distillery, in Cumnock, Scotland, mixes modern-day single malts to re-create whiskies from famous, long-dead distilleries. But a great blend doesn’t have to be particularly innovative: Black Bull, which was first made in 1864, offers a single rich and slightly smoky flavor profile across a range of ages and prices.

And while some whisky fans would never be caught with a dram of Johnnie Walker in hand, the brand, owned by Diageo Plc, makes some exceptional blends, especially on the top shelf. This year it released Ghost and Rare, a $400 blend optimizing its limited stocks of whiskies from storied but defunct distilleries such as Brora.

So next time you’re at the liquor store looking for a whisky, pause before you reach for the Glenfiddich. Try out a blend. You may never stand for a single malt again.

Risen is the author of Single Malt: A Guide to the Whiskies of Scotland (Oct. 16; Quercus, $30)

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Justin Ocean at jocean1@bloomberg.net, Chris Rovzar

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.