Radical New West Side Story Paints an Angry Young America

A team of Europeans is bringing a 21st century vision of America to Broadway.

(Bloomberg) -- In spring 2016, Belgian theater director Ivo van Hove was in New York, preparing his Broadway production of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. Between rehearsals, he found himself captivated by the crowded and chaotic Republican presidential primaries. Like the rest of the country, he watched in awe as Donald Trump moved from the sidelines to center stage in a drama as startling as Miller’s.

Van Hove realized that the issues bubbling up in the campaign—racism, immigration, issues of integration, tribal loyalty—were all in a certain 1957 musical, van Hove realized. “I thought: Well, West Side Story talked about this in a very accessible way,” he says. “With great music.” After directing a string of critically acclaimed reinterpretations of American classics, including A View from the Bridge and A Streetcar Named Desire, among others, he decided the Shakespearean story of star-crossed lovers in midcentury New York would come next.

One presidential election cycle later, van Hove’s West Side Story will open on Feb. 20 at the Broadway Theatre in a production that feels as urgent as its themes, thanks to a slimmed one-act structure and video projections that leave the vast stage bare for hurricanes of dancers to blow through. (The production will precede Steven Spielberg’s big-screen remake of the 1961 Academy Award-winning film adaptation, due in December.) Six decades after its debut, it seems West Side Story is again the story of our time.

Reinventing a Treasure

Back in 2016, after Trump secured the nomination, van Hove took his vision to producer Scott Rudin, who liked it. But van Hove had a few conditions. “I want to make a West Side Story for the 21st century,” he told Rudin. “Not a recreation of what it was in the ‘50s.” In particular, that meant new choreography.

New moves are hardly a radical request for your typical musical revamp, but the choreography for West Side Story by Jerome Robbins, a dance and theater legend who also conceived and directed the show, is sacred. It may be the most celebrated in American musical theater, thanks largely to the success of the film Robbins co-directed with RobertWise. Think of those crisp, menacing finger snaps; the hungry, open palms reaching skyward; and Rita Moreno as Anita, spiritedly tossing back her head at the ecstasy of being in America.

“There had been ambitious dances integral to a show’s plot before,” wrote dance historian Deborah Jowitt in her biography of Robbins, “but none in which dance is a way of defining character from the outset.”

Eyebrows were raised, then, when van Hove brought on board choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, a compatriot who traces her dance lineage to the American post-modernists, an influential group that, beginning in the 1960s and ‘70s, eschewed spectacle in favor of such pedestrian movements as walking and shrugging. In the early 1980s, while Robbins was prolifically creating work for New York City Ballet uptown, De Keersmaeker, who lived in New York for a time, was downtown absorbing the ethos of abstraction from such artists as Trisha Brown and Yvonne Reiner. (She also saw Cats on Broadway, which was not her thing.) Van Hove says he invited her to do the show because “her dance is deeply rooted in New York.”

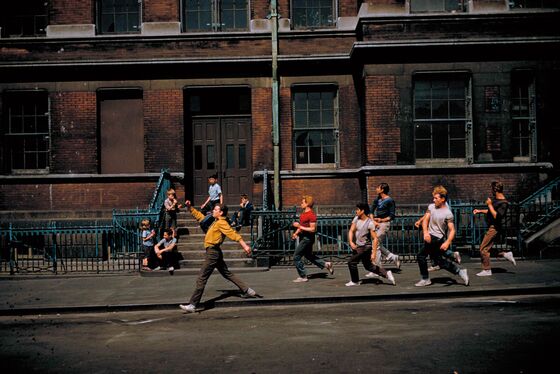

De Keersmaeker was intrigued by van Hove’s invitation—and cautious. “I could only accept [the project] if I was allowed to relate to my own past and vocabulary and way of working,” she says. De Keersmaeker calls herself a formalist, meaning she pays more attention to patterns and spatial relationships than to character and story. That philosophy is clear at the start of this production: Instead of launching straight into the famous, 10-minute, wordless opening ballet, De Keersmaeker scraps the snaps and introduces characters through grim-faced posturing and subtle shifts in balance, projecting their power through stillness, rather than motion.

But musical theater audiences aren’t as patient as the ones who go to concert dance. They expect excitement. “I was not used to thinking in those terms,” she explains. “I had to sharpen my pencil. I learned a lot.” She had to find a way to mix abstraction with the plot’s emotional demands. One vivid example comes at the conclusion of Tonight, a ballad sung shortly after protagonists Maria and Tony first meet. De Keersmaeker creates a tableau fit for a Renaissance painting in which the lovers are held back by their respective clans as they fight to connect. It’s a simple, nearly still, poignant image that casts a shadow of foreboding over what is usually the show’s uncomplicated romantic apex.

A Vast Screen—and YouTube

Frequently in this production, the entire back wall becomes a movie screen, sometimes capturing live scenes on or just off stage. At other times, the camera tracks along empty New York streets (vacant until we stumble upon a dreamlike, distant dancing figure). There are prerecorded images of the actors up close, which serves to supersize their emotions. At times, it can be difficult to know where to look, or challenging to focus on the human bodies dwarfed by their amplified images; yet, for better or worse, the method may speak to young audiences in the digital language they know best.

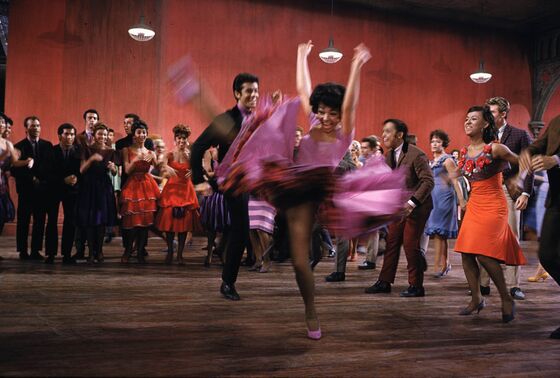

De Keersmaeker herself turned to YouTube, which she calls “the hugest dance library,” to study forms of urban dance such as hip-hop, house, krumping, and Latin dance styles. “There are so many styles that we’re doing,” says Dharon E. Jones, who plays Riff, the Jets’ leader. “It speaks to the melting pot of people in the show, the melting pot of people in New York, and bringing all those backgrounds onto the stage.” For the raucous Dance at the Gym, for example, the opposing gangs assert their dominance through artful strides and assertive leaps in their own ways: The Sharks use more Latin steps; the Jets employ house dance footwork and floorwork.

These styles were not part of De Keersmaeker’s own physical vocabulary, so she and van Hove brought in veteran Broadway choreographer Sergio Trujillo and Patricia Delgado, a ballerina from Miami, as consultants. They spent days with the cast adding Latin and house dance details—decorative moves for the arms and hips—that De Keersmaeker then integrated into her style.

That process stemmed from conversations around identity and representation, which, in many ways, are baked into the DNA of Arthur Laurents’s original book and Stephen Sondheim’s original lyrics (Jets member Anybodys was already genderqueer in the film), and De Keersmaeker and van Hove updated and heightened it in their version. This revival’s casting became a statement of its values and added an important insight: Both Sharks and the Jets are multi-hued gangs to such a degree that they become indistinguishable at times.

Blurring Color Lines

“I never saw myself playing a Jet, because I thought they’d always be white,” Jones says. “I never thought there’d be black people or Asian people as Jets. It’s special that people of color are playing all parts in West Side Story.” The blurring of the previously firm lines between the gangs highlights their shared experiences. As De Keersmaeker describes it: “They're both immigrants. And they're both asking for recognition. And they're both facing poverty.”

This is starkly illustrated in the musical number Officer Krupke, which the Jets sing about a local policeman who’s been harassing them. In the film, it’s practically a gag number; in this revival, it becomes a screed against police brutality and mass incarceration. During rehearsals, the creative team initiated a dialogue about those issues, inviting cast members to share their experiences and perspectives.

“They encouraged us to bring ourselves to the show so the team can speak to the audience,” Jones says. “It means the world to us.” Officer Krupke may be the show’s most radical update, more than its new choreography—in a way, the show’s thesis. “It's about the structural abuse of institutions, the police, the justice system, the social system, the health-care system,” van Hove says. “It was very clear that this was a very political song.”

And it helps drive home the idea that the issues the show grapples with—the toxic camaraderie that comes with shared hatred, the demonization of difference—are issues waiting for viewers right outside the theater. Now, in 2020, another combative presidential election is in process. The man who once stood on the periphery of the debate stage is well-poised for reelection. And two Belgian artists have reimagined a quintessentially American story to confront new audiences with the tragedy at its heart.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Rovzar at crovzar@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.