Music Industry Rethinks ‘Urban’ as a Genre for Black Artists

Efforts to root out racial discrimination in the music industry have coalesced around a single word: urban.

(Bloomberg) -- As protests against racial injustice sweep the world, efforts to root out discrimination in the music industry have coalesced around a single word: urban.

Warner Music Group Corp., one of the three major record companies, plans to stop using the term to refer to music by black artists, according to a person familiar with the matter. IHeartMedia Inc., the largest radio company in the U.S., also will phase out the expression, opting for hip-hop or R&B instead.

They’re following Republic Records, the home of Drake, Taylor Swift and the Weeknd, which said Friday that it would ban the term from company communications. Republic, part of Universal Music Group Inc., is one of the most successful record labels in the world and counts many of the biggest black stars among its artists.

Categorizing black performers as urban has been a sore point for many artists and executives, who see it as a subtle but pernicious form of racism. It groups together a range of genres -- including rap, R&B and pop -- but the main purpose seems to be to separate that music from the work of white artists.

“It’s always made me feel very uncomfortable,” said Nathaniel Cochrane, a producer and manager at Mad Into You. His firm represents producers and songwriters who have worked with acts such as Harry Styles, Khalid and Chance the Rapper.

“It allows certain white people to use it against us, against the black community,” he said.

The music industry has scrambled over the past two weeks to show its support for the black community, pledging hundreds of millions of dollars to fight racism and promising to hire more black executives. There wouldn’t be much of a music industry without black artists, who helped create jazz, rock, hip-hop, R&B and just about every other popular genre.

Cochrane has been speaking with executives across the industry about creating mentorship programs for young black executives and improving diversity on the boards of top companies. While some changes will take months -- if not years -- banning urban can be done now.

‘Just Change It’

“Don’t make a song and dance about it -- it should have been done years ago,” he said. “Just change it.”

The use of urban in reference to music stems from the radio industry, which initially excluded black artists from its most popular stations. The medium started playing more black music during the late 1940s and 1950s, inspiring acts such as Elvis Presley, and eventually it dominated radio -- but divisions remained.

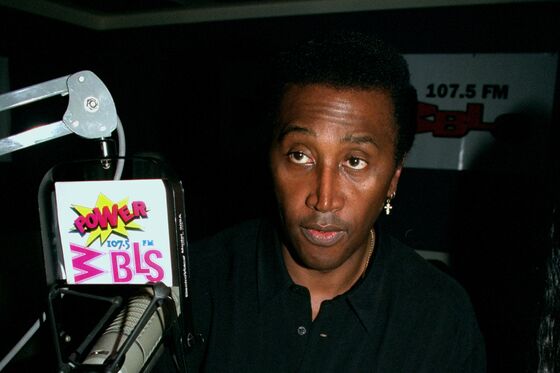

Frankie Crocker is credited with first applying the term urban to music. Crocker, a DJ for New York’s WBLS, used the term “urban contemporary” to describe the range of music he played on his station, which included everyone from James Brown to Doris Day. Urban then cropped up all across the music industry. Record labels hired executives to promote their artists to urban radio, while booking agencies enlisted people to book urban acts.

The word enabled radio stations to sell advertisements to companies that were put off by the word black, and also served as a way for black executives to get promoted. That history is why many black executives, particularly industry veterans, have been reluctant to eliminate the word.

“Please don’t move the current conversation away from the real issue!” Azim Rashid, the head of urban promotion at Columbia Records, wrote on Instagram. “#Urbanmusic divisions were built to give Black executives a true voice and an opportunity to run and manage an aspect of the business that was largely being ignored by the corporations.”

But in recent years, the word has come to be seen as an outdated phrase that excludes black artists rather than including them. Take the Grammy Awards. They created a category for urban music -- the urban contemporary album -- that typically goes to a black performer. But those musicians have frequently been shut out from bigger categories such as album of the year or pop album of the year.

Grammy Update

Changes could be afoot there, too. On Wednesday, the Recording Academy plans to announce its plans for next year’s Grammys, following a vote on proposals by its board of trustees last month.

Pigeonholing artists artists into a category like urban also limits the amount that performers can make, either from radio or labels, said Daouda Leonard, a music manager for artists such as Grimes.

“If you are only urban, you are only worth a certain amount of money,” he said. “Your actual earnings and value as an employee is diminished because of a construct that’s not real.”

Some members of the music industry had already abandoned the word. Billboard has used R&B, hip-hop and adult R&B to describe radio formats, and record companies have avoided using urban to describe some newly created jobs.

Executives at Vivendi SA-backed Universal, the world’s largest music company, have been debating the word for the past few days as part of a new task force to combat racial inequality. Similar conversations are occurring at Sony Corp.’s Sony Music Entertainment, the other of the three major music companies.

While executives debate the proper language and processes to use, artists have spoken.

“I don’t like that urban word,” Tyler, the Creator said at the Grammys in January. “It’s just a politically correct way to say the N-word to me.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.