Pandemic Therapy for the 1 Percent: More Money, Different Problems

“They say, ‘I’m paying $90,000 per month to stay here, and I can’t go outside to take a walk?”’

(Bloomberg) -- It was a haircut well worth $2,000—at least according to one of neuropsychologist Judy Ho’s patients. As California’s lockdown continues, she’s watched agog as some folks in her Los Angeles-based private practice continue to flout it.

“Because of their wealth, some of my clients have felt largely invincible for a long time, but now they feel so powerless,” says Ho, who’s also a tenured professor at Pepperdine University and whose client base is largely Angeleno 1 Percenters. “How do you take back that power? You pay someone top dollar to do your hair.” (She notes that the client didn’t consider how desperate unemployed stylists must be to break rules for a cut ’n’ color.)

Other anxiety-stricken clients have opted to move into residential treatment centers to hunker down, only to find themselves chafing at separation from their families and the regulations under which they’re expected to live there. “They say, ‘I’m paying $90,000 per month to stay here, and I can’t go outside to take a walk?’”

Another client—who opted to technically self-isolate at home, rather than check into one of those facilities—is proving more troublesome. She’s so high-profile that she can’t be left alone and requires bodyguards. Yet she doesn’t socially distance from them, insists on going out regularly for drives, and won’t wear a mask. Two of her security team have quit.

“She’s a bit selfish, but it’s more that she doesn’t really understand the direness of the situation. She is an on-and-off substance abuser, too, who might be high when all these people are quitting [their jobs] around her,” Ho says. “We had a nurse who used to go and do her substance abuse testing every morning—you know, draw her blood and take her urine. She just quit, too, because my client wouldn’t respect social distancing. Now we’re desperately trying to hire someone else to go there.”

Coping in the current pandemic is tough in many ways, including psychologically, so it’s no wonder that many therapists such as Ho have seen business surge as clients turn to them for guidance amid the unknown. Doctors who specialize in high-net-worth patients are encountering problems distinctive to their clients, and so they’ve found ways to ensure their own self-care and psychic soothing.

Ginger Poag, who’s based outside Nashville and whose client roster centers on senior figures in the country music industry, estimates that she’s 20% busier than normal. Now she takes time to do her yoga nidra (a kind of guided meditation) daily, rather than three times a week, which had been her routine. The practice is believed to function like a turbocharged nap; devotees claim that an hour or so might refresh you as much as several hours’ sleep.

Poag’s client base felt the impact of the downturn immediately, because they’re not earning money from touring or shows. They often have the added stress of dependents such as parents they support. Still, for those with several homes, many have adopted the solution of rotating among their houses by private jet.

“They will wait while the staff comes in to clean, get groceries, do all the housekeeping” at one location, Poag says. “They’ll wait a certain amount of time, maybe three days, with no one entering the house, then they’ll move there.” Once bored with those surroundings, they’ll charge staff to tee up another location—the Palm Beach, Fla., house, perhaps—and repeat the process.

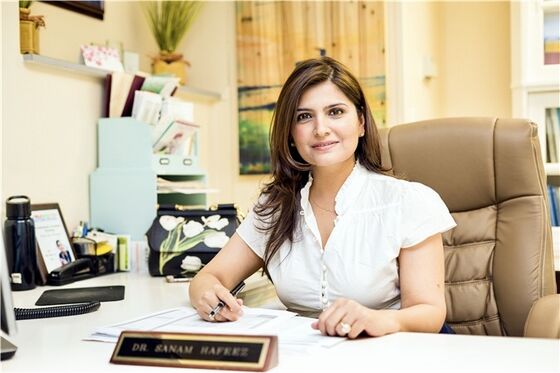

Sanam Hafeez’s clients are also worried about houses—although in her case, the Manhattan-based therapist is hearing more about vacation rentals. “One patient is neurotic that she won't find a ‘great’ Hamptons rental, because all the prices will be sky-high because people in New York City have already decamped to the Hamptons. She is worried that the house she and her husband will be able to afford will be too modest to show her friends,” Hafeez says.

Another patient frets over her appearance. “She’s obsessed with the fact that she has gained weight in quarantine and cannot have her trainer now, as she usually does five days a week. She is truly in a panic about looking ‘bikini ready’ in time for summer.”

That’s not to say that these sorts of anxieties don’t also run among the less wealthy. At root is the loss of one’s sense of “normal,” however defined. Money can allow someone the space to fixate on what might seem a secondary concern to an outsider with a primary concern—such as not having a paycheck. “It’s more about being obsessive-compulsive,” Hafeez says.

She’s focusing on how the lockdown has given her unexpected bonus time with her 5-year old twin boys. “I think they might look back fondly on this time—and so will we. We’ve never had this kind of unfettered access to our children without all the running around to class or swim lessons.”

Her motto for herself and others spending unexpected bonus time with their children is simple: “Cherish and enjoy it.”

Resa Hayes, an expert on co-parenting mediation and family therapy, splits her time between the 1 Percenter enclaves of Aspen, Colo., and Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Her clients often share children but live in different states, she explains, and normally can easily shuttle between them by jet.

The pandemic has made those plans more complex: One client lives in a blended family in L.A., while her former spouse and their 6-year-old daughter are based in Aspen. “So she ended up coming to Aspen on their private jet with her infant until this levels out; she left her new husband and stepchildren in L.A.” This unusual situation, and the woman opting to move temporarily to Aspen, muddies the agreement between the exes, of course, in ways that Hayes expects to hear about.

Another of her clients is the mother in a family on Park Avenue on the Upper East Side. “She must be 55, and this is the first time she’s ever cooked anything for her family,” Hayes says. “The biggest dilemma of her day right now is which brownie mix to buy at the grocery store. She is loving it in some ways—staying at home, acting like a domestic goddess. But I don’t think she will keep cooking once this all passes. It’s fun, but it’s vacation-style fun.”

Hayes finds solace amid the stress from the outdoors: Aspen’s jet-set reputation was first built on its natural beauty. “Go for a walk in nature now. It’s a reminder that some things haven’t changed, no matter what happens to your portfolio or people getting sick,” she says, “I think the most dangerous part of Covid-19 is the loneliness part. So I make sure to connect with people who are beyond my work circle or my own family. It soothes me to have conversations beyond that.”

Having money may make this time pass easier, but it doesn’t inure one from tragedy. Connecticut-based Darby Fox has been helping one client through the aftermath of a 60-year-old Wall Street titan shooting himself after suffering huge losses.

“If you think of yourself as an omnipotent person with control and power, it’s unbearable when that is taken away. The only solution is to get out—it’s an all-or-nothing mentality,” Fox says. (If you or anyone you know is struggling, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can help at 800-273-8255.)

Fox’s family therapy business is up about one-third since the pandemic hit, and she’s also seeing the emotional impact of shelter-in-place on couples unused to sharing each other’s space, or even each other’s lives. “In an affluent relationship, you can easily live an almost completely separate life from your spouse, normally. The only time you’re together is in a very social setting—say, cocktails at the club. Suddenly, now you’re in the same space and can’t turn to the outside to help with your needs.”

“It doesn’t matter how many square feet you have, you only have each other,” she says, citing one couple. He works in Manhattan, and effectively lives there during the week while his wife remains at the family’s main home on Long Island. They’re now living together out east, and their relationship is strained. “All of a sudden, he’s in her space and he feels like he should be her priority. They can’t get anything right. Even what they’re having for dinner is an argument.”

Fox, though, is finding some joy in the changed circumstances of the pandemic—all of her own children, twentysomething professionals, have moved back home until New York City normalizes. They do yoga together or cook dinner as an entire family (in her case, argument-free).

More than anything, though, she’s seized the chance during the lockdown to relax a little. Yes, she has more client appointments than ever, but she’s no longer commuting. With extra time on her hands each day, she posed the same question to herself as to her clients: “Where do you find joy?” For Fox, the answer was keep it slow and simple: “I stay in bed and do a little reading. Everybody wants to feel productive during this time, but the most important thing is to figure out what you consider productive,” she pauses, “It’s OK to dial it back a little.”

Los Angeles’s Ho knows exactly what Fox means. The frenzy among her high-net-worth clients has required her to restate her boundaries, even when interacting virtually. She’s long insisted that demanding patients who bombard her with text messages finesse their communications, marking truly urgent messages with “A,” less-urgent ones with “B,” and so on.

Recently, she’s had to remind folks of that again, including one older male client, a major chief executive officer who seems to mistake Ho for one of his five assistants. He said he would pay her double if she prioritized every one of his voicemails and texts. She told him that he should follow her system—or she could recommend another professional.

“I’ve offered [a referral] a few times,” she says, “but I’ve not had anyone take me up on that.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.