If You See One Art Exhibit This Season, Make It This Blockbuster

If You See One Art Exhibit This Season, Make It This Blockbuster

(Bloomberg) -- This June, when the art world descended on Basel, Switzerland, for the city’s annual art fair, the must-see event wasn’t in the booth—it was the Bruce Nauman retrospective at the Schaulager. Reactions tended to fall into two camps. The first was outright adulation. The second was about how it would look when it traveled to MoMA in the fall.

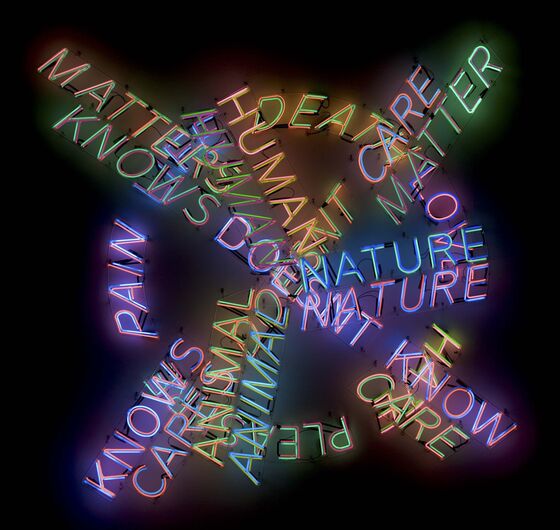

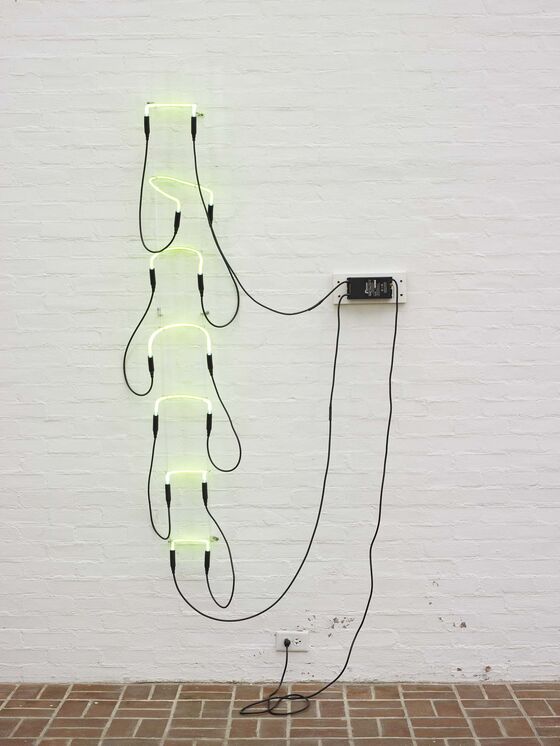

Now the show—Nauman’s first U.S. retrospective in 25 years—has finally arrived in New York. “Bruce Nauman: Disappearing Acts” runs from Oct. 21 through Feb. 25 and takes up the entire sixth floor of MoMA in Manhattan and the whole of MoMA PS1 in Long Island City, Queens. There are 165 works from almost 70 lenders, including rare sculptures, paintings, installations, videos, drawings, and performances. Nauman’s most recognizable art is probably his work with neon: Multicolored figures run, and walls of words and phrases blink on and off, their messages changing dramatically based on which words are lit. His art doesn’t have a unified aesthetic—his minimal, occasionally massive sculptures have little in common with the neon works—but almost all of it is, in some intrinsic way, an experimentation with art with a capital “A” that actively engages the viewer.

At MoMA, all of the walls have been removed from the sixth floor galleries for the first time. “Given Bruce’s work, I realized we could capitalize on its grandeur and allow his architecture to create the architecture of the exhibition,” says the show’s lead curator, Kathy Halbreich. “There’s space that couldn’t be seen normally because of their architectural scale.”

A Major Reappraisal

In the midst of the current vogue of “rediscovering” artists, Nauman is an unusual case: He’s been a firm fixture in the pantheon of American art since his 20s. (He was born in 1941 and had his first solo show at the famous Leo Castelli gallery in 1968.) And while he’s seldom considered the hottest artist around, he’s popped up with enough regularity that no one could argue that he’s a hidden gem.

Yet there is a sense that this retrospective represents a major reappraisal of Nauman’s art. “Twenty-five years is several generations,” Halbreich says. “Everyone knows [his work] from books, or a clip on YouTube, or a piece they’ve seen here or there.” Suddenly, she says, people will be able to get “the real experience,” which, as it happens, is strikingly relevant today: “The world caught up with Bruce,” Halbreich says. There are sculptures from the 1970s with security cameras and monitors that draw attention to surveillance. In one, Corridor Installation (Nick Wilder Installation) from 1970, the viewer walks down a narrow hall toward a small monitor, only to discover the monitor is displaying a livestream of the visitor. “Even environmental concerns,” Halbreich says. “L A Air, this little beautiful book that’s upstairs, is photos of the polluted sky.”

There hasn’t been a Nauman show of this magnitude for so long, Halbreich explains, simply because Nauman, who’s now 76, didn’t want one. “After every major show, there’s a slowdown of what gets made in the studio,” she says. “It’s almost paralyzing. He’s talked about how retrospectives are a major pain in the butt.”

Market Implications

As a consequence, Nauman, to many, has been an historical figure rather than a figure of the moment. And that leads to the other reason the show is being received with such fanfare: The reintroduction to the public could have major implications for the market for Nauman’s work. “It’s definitely going to do something [to his market], and I think it already has,” says Lisa Schiff, senior adviser at Schiff Fine Art, an art consulting firm. “But it’s not going to be like George Condo,” an artist whose market has exploded at auction in recent years.

And at least from an auction perspective, Nauman’s sales record doesn’t follow a linear trajectory, up or down. He’s had more than 1,000 works come to auction, according to Artnet, with 21 works selling for more than $1 million each.

But every time his secondary market seems to gain momentum, it inevitably slows down. His auction record was set 17 years ago in 2001 when a plaster sculpture Henry Moore Bound to Fail (Back View) sold for $9.9 million at Christie’s New York. The next highest lot was sold in 2016, but a look at his top 10 auction records will stretch back to as early as 1992. That early sale, a neon piece called One Hundred Live and Die, which Nauman made in 1984, sold for $1.9 million at Sotheby’s New York. (Adjusted for inflation, that would be $3.4 million in today’s dollars.)

Schiff says at public auction that irregularity might not change, at least not any time soon. “I think market moves won’t be so visible,” she says. “I think some of these pieces are in serious collections, and every now and then those collections come up for sale. But this show isn’t going to shake that out.”

Instead, Schiff says, the real impact might be felt by Nauman’s dealer, the downtown New York gallery Sperone Westwater, which has exhibited Nauman since 1976 and sells his new work on the primary market. “It’s a great gallery that’s not on everyone’s radar,” Schiff says. “It’s an amazing space, but there isn’t an energy emanating from there, which might be good for him.” (Sperone Westwater didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.)

An End in Itself

Leaving aside market considerations, the show is almost certainly going to be a hit.

Nauman is the rare conceptual artist who makes works that can be enjoyed by the casual museum-goer, and his sculptures include enough spectacle (there are fountains, motorized mobiles, and I-beams hung from the ceiling) that they should satisfy even the most superficial of culture-seekers.

As for his market? Halbreich says that in her experience, Nauman couldn’t care less about what his art sells for. “I don’t think it’s an adamant resistance to the market,” she says. “I think it’s a ‘I really don’t care—I just want to do what I do in my studio, day in and day out.’”

Nauman, who fled New York in the 1970s, still does have a place in the city, Halbreich says. “And it looks like a dormitory. You go in, and the suitcase is open on the floor. The nicest, most ‘done’ room is the kitchen. I don’t think he needs more money.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Chris Rovzar at crovzar@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.